Every antique store has a basket — squeezed onto a corner of a shelf of an overfilled display case — with a pile of postcards.

If the store suffers from the scent of mildew then the cards are a bit heavy and thick when you lift them. If it’s dry and dusty then they may feel a bit brittle.

Unused postcards need to clear a hurdle of artistry to merit attention. The ones on the top are dog eared but the paper of the lower ones is starting to get comfortable with each other.

But the used ones… the used ones, after looking at a few the thought must cross anyone’s mind: Who was this person?

Just an answer to that seems daunting. So imagine if you looked at a card, maybe on a hot day like Alice or just after a couple of drinks, and found yourself slipping down into its story?

Note: A digested version of this article appears on Capitol Hill Seattle Blog.

The postcard

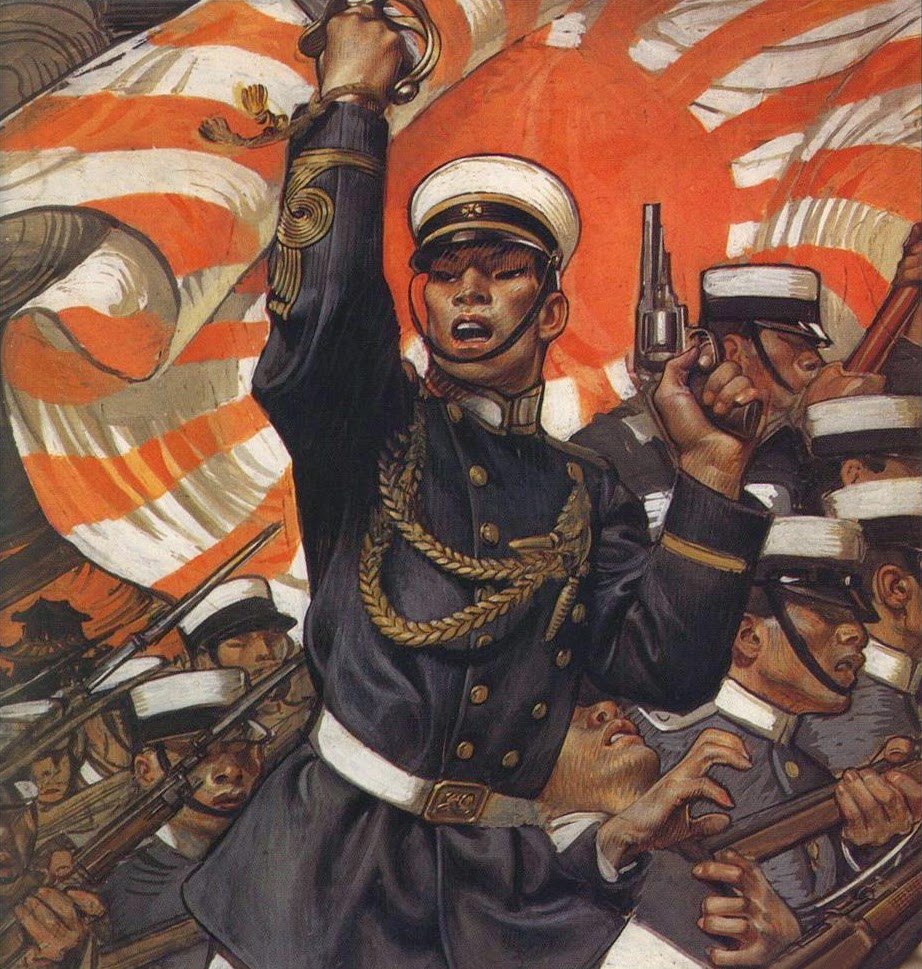

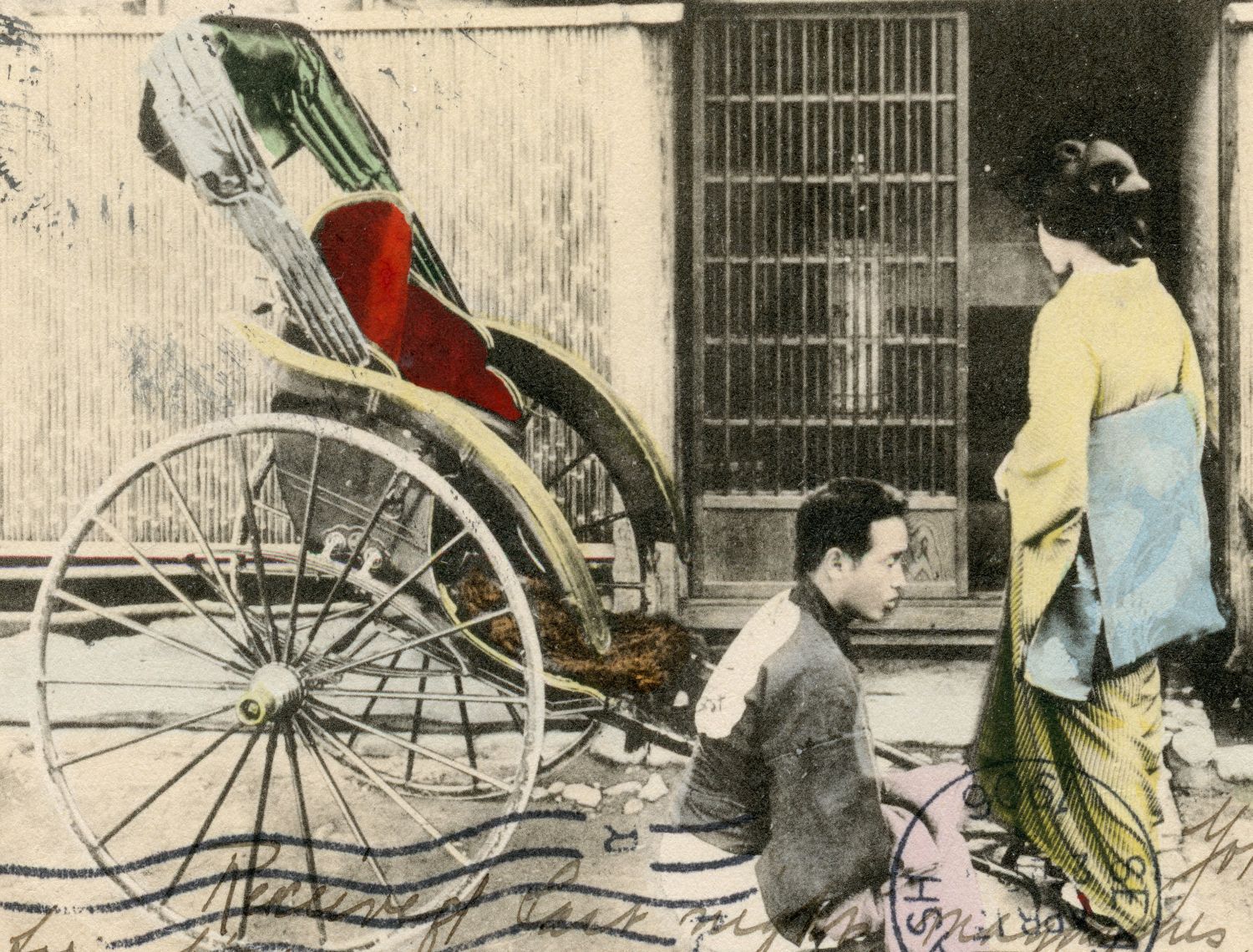

The postcard itself was part of a series of 12 depicting a day in the life of a young woman, O-koto-san (Koto). She gets up, reads a letter from her fiancé at war, visits a friend for the day, and comes home again to go to bed. I wasn’t able to find many copies of cards from this series online, so it seems relatively rare. All of them have dates later than this. So I believe the series dates from 1905 during or just after the Russo-Japanese War.

The postcard is titled, “O-koto-san takes a ricksha and starts out”.

The young woman Koto lives a very fancy life per the series. Given that both she and her friend Hana are addressed with O- and -san, it’s safe to think that she is a geiko, a geisha in training.

Another thing from the title that I’ll point out is “rickshaw”, now a standard English word. Its origin was the Japanese word jinrikisha (人力車) which literally means “person power cart”. By dropping “jin”, the English word actually just means “power cart”. We should have gone with jinriki or jinshaw or something.

The image itself was printed in simple black and white, and then hand-colored. Other examples of this postcard available on the internet show obvious variance from being painted by hand. In one case the top of the rickshaw is a different color.

This was common worldwide until the 1930s. Japan had a well-established and very artistic coloring industry, though, which makes this card seem a bit cheap in contrast. Here are a few examples of contemporary cards that are beautiful.

Postage

The date in Yokohama was “30 3 06”. March 30th, 1906. I can’t make out the day but it arrived in Seattle in April 1906.

Even without the dated ink stamps we could figure out about when this postcard was sent. The postage stamps are for 1 “sn” (sen) and 3 sen. The stamps feature a pattern with a chrysanthemum in the middle that was produced from 1899 to 1908. A sen was 1/100 of a yen (a yen is about a U.S. penny currently), and discontinued in 1953.

Japanese postcards from this era had one side for address and official use, and the other for picture and message. So the sender of this postcard had to squish his message into the lighter area on the bottom right of the image.

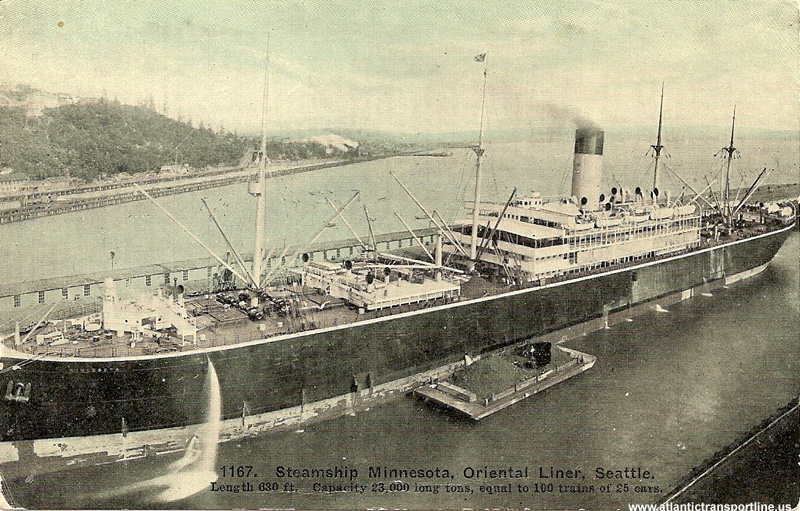

S S Minnesota

The postcard was carried to Seattle on the S.S. Minnesota. The Minnesota was barely a year old, and at 622 feet long and 75 feet wide was the largest cargo ship flying the Stars and Stripes.

The Minnesota made the trip carrying this postcard in a record 13 days, docking in Seattle on April 15, 1906.

In the holds along with the postcard and other mail were 5000 tons of merchandise from China and Japan. In 1906 a full half of the United States’ imports from Japan were silk, so it’s a safe bet that there was quite a weight of it on this trip too. An article in the Ranch on the day of the Minnesota’s arrival trumpeted Seattle’s position controlling trade with Japan and the rest of Asia,

“In relation to the Oriental trade… it is remembered that ten years ago this business was largely carried on by Japanese steamers of no very large tonnage, while today several immense steamers are finding more business than they can readily take care of. Two of these big steamers are the ‘Minnesota’ and the ‘Dakota,’ sister ships of the Great Northern Steamship Co., each with a capacity of 28,000 tons.” (The Ranch, April 15, 1906)

Three days later the Great San Francisco Earthquake struck, destroying much of the city and leaving many homeless. Seattle and Puget Sound cities gathered relief supplies to send. Due to the large volume there was talk of sending the Minnesota, which could also house 5,000 people once it arrived. Instead the Queen and Meteor filled up their holds and headed south. Because the Pacific Mail steamer Mongolia was pressed into service as a hospital ship, all mail to Asia was rerouted to the April 29th sailing of the Minnesota.

Passengers

The Seattle Star reported that the British ambassador to Japan was on the Minnesota on the trip from Japan to Seattle. He was one of 122 passengers including 64 Japanese and three Chinese citizens. Two U.S. Navy officers were aboard, Captain Milton and Mr. Barclay.

The Japanese included a member of the House of Peers, Chokichi Kikkawa, and historian Hideo Segawa among others. One large contingent was a group of electrical engineers headed to London for the first meeting of the International Electrotechnical Commission, one of the first international standards bodies. (My grandfather was a member of the IEC and I’ve scanned and posted many of his photos from yearly business trips to Europe for conferences.) The head of that group was Ichisuke Fujioka, founder of Toshiba and remembered as the father of electricity in Japan.

Minnesota afterwards

The Minnesota’s voyage back to Japan on April 29th carried more than 350 people. The Seattle Times reported that Alice Gilman, niece of the the railroad builder (Burke-Gilman Trail), would travel with her mother. Less important locally was the new U.S. ambassador to Japan, Luke E. Wright.

The Times also cataloged members of a group of 50 Army corpsman headed to the Philippines to build a railroad. The Seattle Star listed a few large groups: a commercial excursion from Los Angeles, a group of mine magnates from New York, and a group of 30 school teachers headed to the Philippines.

An Everett Evening Statesman article from April 9th described the teachers in more detail. They were the first group of 100 total teachers that the U.S. War Department hired for at least two years. There were three teachers from Washington State: John C. Early of Spokane, Edward Geise of Spangle, and Roy M. Porter of Dungeness.

Likewise an April 9th Seattle Times article described the mining magnates. 55 men traveled to The Philippines to explore the islands for rumored mineral deposits.

After ten years of four money-losing trans-Pacific trips per year, the Minnesota sailed from Seattle for its last time in 1915.

After suffering failing boilers on the way south to Cape Horn to support European trade during World War One, the Minnesota finally made it through the Panama Canal in 1917. Seven supply trips were made to Britain before the war ended, and then three loads of 14,000 total U.S. Army troops back from France.

That was the end of the Minnesota.

The Gullixsons

In 1906 there were four residents of 708 East Union Street in Seattle, where the postcard was delivered. They were all Gullixsons: Edna, Harry Severin, Henry Ferdinand and Marie Agnes.

Edna was a senior at the University of Washington. She was preparing to graduate when the postcard arrived.

H. F. Gullixson was born in Norway in 1848. With his sibling he started the Gullixson Brothers carpet and oriental rug store in San Francisco. He married Marie (born in Cincinnati, Ohio) there in 1869, and they raised four children. In 1887 Henry and Marie were living in Portland, Oregon as Gullixson Brothers apparently expanded into new territory. By 1895 the store was gone and Henry was selling insurance.

After a brief stint selling carpets for the White House Company in Spokane, Henry brought the family to Seattle in early 1902. He continued to work for others. He ran the oriental rug department for Frederick & Nelson, which was only a decade removed from its origins as a furniture store. He led carpet sales at Frederick & Nelson for at least 29 years, until just before his death at 84.

Harry

While the family lived in Portland, our postcard addressee Harry was working as a clerk at the Columbia River’s venerable train and boat firm Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company. Harry stayed in Portland after his father took the job in Spokane and the rest of the family left as well.

Harry’s sister Marion married Seattle insurance salesman Morten Atkinson in 1896 and over the next five or six years all of the siblings and their parents drifted to Seattle. Harry was in Seattle in 1900 and took a traveling sales job with Chicago meat packer Armour & Company by 1902.

Later, after he was done with Armour he turned to the family’s fallback profession, becoming an insurance salesman himself.

Harry at Armour

Harry applied for a passport in May 1904 to travel for Armour & Company. No photograph was attached but it described him as 5’10”, brown eyes, medium aquiline nose, large mouth, square chin, dark brown hair, smooth face, and fair and ruddy complexion.

From the postcard, it’s easy to guess that Harry used his passport to travel to Japan. But thankfully it’s not necessary to speculate exactly what he was doing. A February 3, 1904 Seattle Times article clearly described Harry S. Gullixson’s work.

Japan and Russia were on the brink of war. The Japanese government stocked up on non-perishable food, such as the canned meats made by Armour & Company. Armour’s manager in Seattle, H. E. Barber, successfully established sales to Japan in 1903. In one week in January 1904 the Japanese navy bought 2,500 cases of meat from Armour. The quantities warranted sending someone over to secure orders directly from the Japanese government. Harry Gullixson from the Seattle office took the job.

Packers in Chicago and other mid-west and eastern cities hoped to sell cheese, butter and meat in large quantities should war really break out.

With the onset of war, Gullixson arranged for the sale of Armour’s share of canned meat that the Japanese Army purchased. 9,000,000 rations in 1905 alone.

The Jungle

While Harry Gullixson was in Yokohama selling Armour’s meat products, journalist Upton Sinclair was working at an Armour meatpacking plant in Chicago. The information he gathered turned into a serialized novel for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason in 1905 and then the novel The Jungle in 1906.

The Jungle had a huge impact on American consumers, leading to the creation of what we now call the Food and Drug Administration. The shock waves can still be felt in the organic food movement today, 100 years later.

One of the greatest ironies of The Jungle was missed even by Sinclair.

Jurgis Rudkus, the protagonist of The Jungle, came to America from Russian-controlled Lithuania. One reason he left was so that “he did not have to go into the army.” Jurgis Rudkus was a fictional character, but he was built on the biographies of real people. The 1938 biography of Philip Armour, Armour and His Times, reaffirmed this: “between 1903 and 1904 the Yards received great numbers of Slavs of all tribes fleeing from Russia because of the Russo-Japanese war.”

So eastern Europeans, fearing near-enslavement and death in Russia’s army, went to work at American meat packing plants. The meat packing plants had slave-like conditions that threatened death. There, they created rations to fuel the Japanese army as it killed the eastern Europeans in Russia’s army.

Meat trade

Exports overall spiked in 1904 and more in 1905, covering what had been a trade deficit with Japan. Government statistics released in June 1906 were described in papers nationwide, listing 1903 exports to Japan at $21 million, 1904 at $31.5 million, and 1905 at $55.75 million. Cloth, leather, food, machinery and railway equipment made up the bulk of trade. All the things necessary to outfit a contemporary army and its engineers.

The sales were so strong that the letdown after the war was spectacular.

American exports of canned beef and canned pork in 1906 were less than half of 1905. Exports of canned meat to Japan dropped from 14.5 million pounds during the first eight months of 1905 (through the end of the war) compared to less than 100,000 pounds in the same period of 1906.

Understandably, Harry Gullixson returned to Seattle after the war ended. Based on our card, he remained in contact with some of the foreigners he knew in Yokohama.

The Message

Scrawled along the bottom edge of the postcard, under the Seattle postmark, there is a simple message of thanks.

Yokohama March 30

Received last night magazines, Posts and Colliers. For writing am very grateful and appreciate your generosity. The mail closes this a.m. so will not have time to write. Now for breakfast and Tokyo train. R.F.

“Posts” must have referred to the Saturday Evening Post. It’s frankly surprising to learn that the Saturday Evening Post is still published today, and that it has been run as a non-profit publication for four decades.

Collier’s was a weekly American magazine with a broad range of content. There was likely a Sherlock Holmes story published in one of the issues that R. F. received. Collier’s also invented investigative journalism (muckraking) in the years just before and just after Harry sent R. F. copies of the magazine. Among the progressive topics was an article in early 1905 by Upton Sinclair about Chicago’s meat packing industry.

The train from Yokohama to Tokyo was a national passenger line started in 1872. The day that R. F. wrote this postcard, Emperor Meiji signed a law greatly expanding the nationalized train network. This was the true beginning of the rail system that we know as JR (Japan Rail).

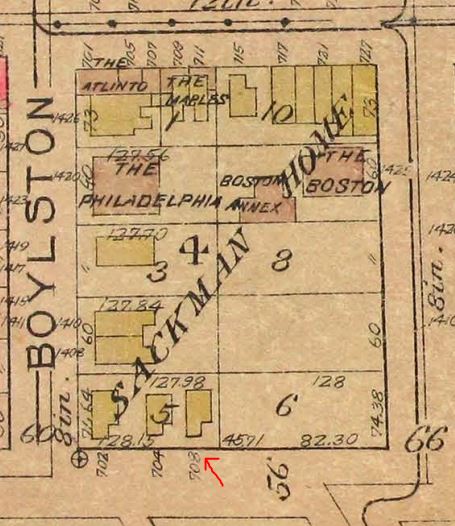

708 East Union

This was not 708 Union, the address of the Eagle’s Aerie Number 1 in Seattle. Occasional misprints place a club incarnation of the venue, Eagle’s Nest, including a 1983 concert by Black Flag, at “East Union”.

Among real mentions of 708 East Union, the first in the Seattle Times was the May 2, 1906 wedding held there for Marion Atkinson (Harry’s sister) and Clyde Leroy. The postcard had arrived just two weeks earlier and perhaps was still on display.

A 1909 ad said that the house had seven rooms and commanded $45 in rent per month unfurnished, rather high.

In the 1912 Baist map it shares a plat with 704 and 702 East Union. Presumably one owner developed all three as rentals.

Closing

It’s a simple postcard, sent 100 years ago from one regular person to another. A postman delivered it to a house just a few blocks from where I sit.

It’s amazing that we used it to travel with it back across the Pacific to Yokohama and discovered just how closely we’ve been connected through global trade for the last century.

UPDATE:

I forgot that I have another postcard sent to Gullixson from Japan. This one is 1908, addressed to Armour & Company.

The message reads “Dear Gullixson – Just wish you a merry Xmas from all here.” But I can’t make out the salutation or name. Inubbful??

Further Reading

- Aoi Bridge: Tokyo walking and its sequel Tamagawa Aqueduct: Tokyo walking

- Akasaka on the Rise: in 2006 I researched, photographed, and wrote about the historic streets of Tokyo’s Akasaka neighborhood in a section of my old website.

- Photos on walks in Tokyo from 2000-2008. In particular I’ll highlight Streetcar Memories, describing the route of the number 38 Jyoto-sen toden streetcar; Walk to Work 4, from Higashi-Koenji to Shinjuku; and Urban River Cycling, from Mitaka to Akasaka-Mitsuke.

- I’ve done some rephotography around Tokyo, including at Tameike, Tokyo’s water source before Tamagawa Aqueduct.

- Rephotography in Nikko

- Rephotography in Utsunomiya

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nice article. And what is the most important – really useful :). I am interested in the list of passengers from Dakota steamship (5.08.1906). Could you help me finding it?