In my history of Seattle’s Groceteria Stores, I briefly described how Alvin Monson’s PTSD from World War One led to the downfall of that grocery chain. This article is a lengthier exploration of his traumatic experience using quotes from primary sources to illustrate the horrors as accurately as possible.

Update January 2018: I appeared on Seattle radio NPR 88.5 KNKX for an interview about Groceteria and Alvin Monson. Listen here.

The Select Few

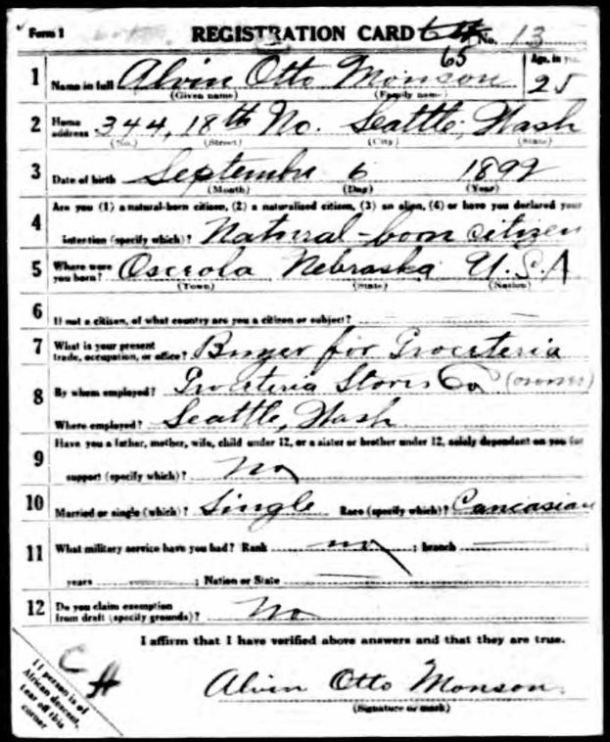

On May 18, 1917 the Selective Service Act took effect, ordering men 21 to 30 to register and for local draft boards to randomly select men to be drafted. Alvin’s registration card indicated that he was the buyer for Groceteria Stores. This was a gross oversimplification, ignoring his executive position, roll as shareholder, and the fact that Groceteria was his brainchild. The card’s personal data described him as tall and slender with light brown hair and blue eyes. The field that would cause him the most grief was “Married or single?: Single”. Many draftees who passed their physical argued that they were the sole income earner for their household, and often they were excused from service.

Alvin was left with only one argument: that he was a critical resource in his business. A September 7, 1917 article in the Seattle Times chronicled Alvin and his brother Martin’s efforts to avoid service:

“Storekeepers Ask President for Exemption

“Alvin O. and G. Martin Monson Appeal From State Board When Called for Service in National Army

“Alvin O. and G. Martin Monson, directors and originators of the Groceteria stores, yesterday filed notice with the state exemption board of this district of their appeals to the President of the United States from the action of the board in denying them industrial discharges from service in the National Army.

“The Monsons were first certified for service by District 8 exemption board, and they filed industrial claims with the state board, claiming that the groceteria business could not be maintained in their absence without heavy losses, and that they were indispensable to the conduct of the business and that their places could not be filled.”

The November 4, 1917 Seattle Times informed readers that the appeals were rejected:

“Groceteria Owners Put on Olive Drab

“Goldie M. Monson and Alvin Monson, two young men from District 8, who conceived the idea of selling groceries on the wait-on-yourself plan and copyrighted it under the name of Groceteria, are among the soldiers at American Lake today. They left Seattle yesterday with the fourth contingent from Seattle.”

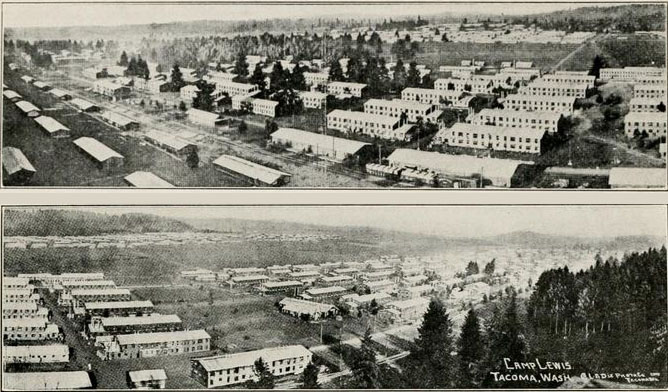

American Lake is a large body of water in Pierce County, southwest of Tacoma and southeast of Steilacoom. In early 1917 Pierce County residents purchased 70,000 acres southeast of American Lake and gave it to the federal government to make a new army base to train draftees headed to Europe. In June construction began and in July the base was named Camp Lewis. This later became Fort Lewis and in 2010 was merged with an Air Force base to become Joint Base Lewis McChord. In November the Monson brothers joined the swelling ranks of the “Wild West” 91st Division at Camp Lewis. While most Washington men were part of the 361st Infantry Regiment, Alvin was assigned to the 362nd which was mainly Utah and Montana draftees. The two regiments comprised the 181st Brigade. Composed of draftees from across the western states, the 91st topped out at 37,000 men in December.

Train to Hell

Alvin and Martin spent seven months training at Camp Lewis and traveling back to Seattle whenever they had a day off. Alvin was assigned to the 362nd in the machine gun company. After a time Alvin was pulled from the daily rifle training to instead use his store management skills in the canteen.

After weeks of rumors the 91st deployed in June 1918. They rode the Great Northern Railroad to New Jersey, where they were staged at Camp Merritt for a week. Then the 362nd boarded the conscripted British transport RMS Empress of Russia for the ride to Liverpool and then the large port of Le Havre in northern France. The crossing took more than a week.

In late July the 91st began moving inland to a training ground at Haute Marne in northeast France. A terrible tragedy awaited Alvin. His machine gun company along with a medical detachment boarded a small freight train for an overnight trip. They were parked on a siding near Bonnieres when another train rushed up behind them. In his words,

“At about eleven o’clock, we were all going to sleep… There were fellows this side and that side and stretched along the car… and then I went to sleep; dozed a little anyway. Then I heard this crash coming. First I heard a big crash and I didn’t know what it was and I said ‘My God, I am going to get through this and I (weeping). I heard a train. I didn’t know where I was, and before I could figure it out — (weeps). When I came to, there were ambulances all along… I ran across the captain. He said “You help four of us clear this up.” We started to carry them on the stretchers like the Captain had said. The first fellow, a man named Copeland, had his head off. I started to lift up again and then my back caught me, just like a shot… There were thirty-three killed and seventy-two injured in that wreck…

“In this second door a fellow asked me to kill him. He was in pain, see. Oh Gee! It was awful. He was yelling, of course. It was the worst you ever see.” — USA vs Alvin O Monson, Ninth District Court #8237

The official history of the 91st Division makes no mention of the train wreck, but it warranted a full chapter in the history of the 362nd Infantry Regiment. The author held back nothing, painting a grisly picture for those that would learn or remember the events of that late night:

“On each side of the track, as far as sixty feet, lay the wreck of box cars, the dead and dying in grotesque positions. As the engine plowed through the last seven cars, it scrambled trucks, wood, iron, bodies and rifles in a tangled mass. Feet and arms peeped forth from the wreckage. Blood and brains and dismembered legs and arms were spattered and scattered everywhere. One body rested under the rear wheels of the engines…

“The only noise was that of the rescue parties, save when the pain of moving brought forth an involuntary groan. With crushed chests, smashed heads, arms and legs broken or cut off, these men lay without a murmur. Men pinned down by the weight of tons on their legs or arms begged the rescue parties to work first upon some of their comrades nearby.

“The dying lay patiently, giving the final words of their life to be written to their mothers, their wives or their sweethearts, or receiving last rites from the Cure’.” – History of the 362nd Infantry

Alvin was not injured but the trauma caused chronic pain that resurfaced throughout his life whenever he thought of the events. He was left behind with two dozen men and a lieutenant to oversee burial of the dead. The soldiers were lavished with food and drink by the French locals. They were constantly drunk on wine for the two days, trying to forget the horror.

After censorship restrictions were lifted in 1919, American Red Cross Lieutenant Colin Dyment had his account of the Bonnieres wreck published in papers across the United States. Dyment skipped over the grisly details except to point out when a man whose legs were shattered or a man whose hand was cut off showed loyalty and determination to enter the war with his unit. He did have a thorough description of the funeral, though:

“The bodies of the thirty dead were taken to the nearby village of Freneuse, and on Friday the 27th a military funeral was held. The French in Freneuse closed their stores. A band of twenty from a French infantry appeared to aid in doing military honors. The prefect of the district, the city officials, a representative of the French senate, one of the French army, and numerous other French officials were present… Flowers were banked everywhere and flags were draped…” – Seattle Times, April 9, 1919

Meuse-Argonne

After the funeral, The 362nd regrouped and joined the 91st for a month of training. In September they headed to the front lines near the Argonne Forest. Alvin was put into a supporting role because of his chronic pain. This meant assistant to the company clerk initially, but later he was assigned as runner for one of the four sergeants just as the 362nd was about to lead a frontal attack on German positions. It was early morning on September 26, 1918. The men went over the top of the barbed wire at 5:30 a.m.

“I didn’t know I had to go into the fight yet. I didn’t realize. I was called three or four hours until he told me I would be runner for the Sergeant; then it was too late, right at the last like that. They knew they were going to go and they could see the horrors of it. You see I didn’t,– I didn’t get into anything, into the fighting…

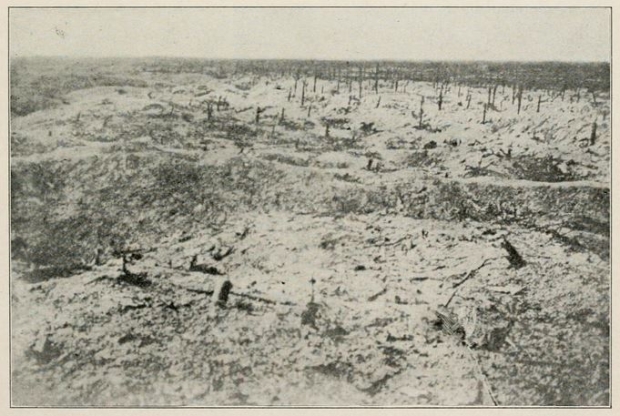

“The American artillery was right back of us. It sounded terrible. You would have to strain yourself to keep the noise out, more was coming all the time, and fast, oh! they were fast, one after another… We went over the top and there was barbed wire across the top. We got over there and we could see… trees knocked down and holes here and holes there, holes all over. We saw dugouts and Germans running out of dugouts…

“By gosh there were a million shells it sounded like. Shells at all places… The first man killed was Lieutenant Stearns [Stearn]. He had his leg shot off… The next man, named Goodwin, one of the runners,– see, there were eight of us — one of the runners for one of the squads — a shell hit him and a fellow said it was a good thing we knew who he was because he was blown all to pieces… A man named Goodwin or Goodman… I would say I was about three-quarters of a block or just about a block away when that happened, and the next thing I heard, the Second Lieutenant,– we were advancing, going through and next Stearns, the First Lieutenant, and then next Lieutenant Swift, was killed. Then a man named Joseph Zulova [Piazzola]. He was blown to pieces. Not like Goodwin. And then we keep on advancing, about five miles and these big shells going all the time, both ways, just generally going and those big shells just whistled. It was cross fire in the air, and machine gun too…

“As we advance, we all got on top of the hill. I got in a shell hole and how those shells, the big guns, 77’s went in all around; around and among the men. All over this hill. I was still in this shell hole. The Sergeant said ‘Come on Monson, let’s go,’ and the others started to advance and as soon as I got out of the big shell-hole and got where the Sergeant was, a big shell came and blew up the hole I had just been in… Then he told me my Captain was killed. He told me right after that. Captain Worsham was killed right on this hill. That left Sergeant in command…

“We were going over this big long hill, and off to the left I noticed a whole lot of soldiers around a tree and a big shell hit that tree and the tree went over and the fellows staggered. On that hill fourteen fellows were killed. I don’t know what happened to the fellows around that tree…

“I started across this ravine; a little bridge went across it. You could go across in that place but I went around and got across and a big shell hit right in back of me. That big shell blew up the bridge, and then I went and lay alongside a tree; a willow tree, I would think, two or three feet the other side of the bank, and then I went and lay down there, and there were six or seven or eight fellows lying right along there… And then a big shell hit. When I came to and raised up all these fellows were all torn to pieces… I heard some shells and sounds like shouts so I started back–. As I said, there were six or seven fellows lying with me.

“I am leaving out some. Going over to this place you see I read something on the boat before I left, just a little pamphlet, I didn’t know where I got it. It said ‘If you believe the things I do,’ something like that, ‘You can do them also.’ It said ‘It is a promise to you.’ I read it when I went to church and thought I could do anything, that there was nothing I could not do. Going over this hill I said ‘They cannot hit me.’ When I raised up from this bunch of fellows and they were all killed I was so surprised. I could not realize it. I thought there was something wrong with this place. I didn’t know, I thought there was something wrong with my mind, surely something wrong when I saw that. I noticed a hole right through my leg, you know these wrapped leggings, and I kept unwrapping it and there was a little German bullet, one of the rifle bullets, right next the skin and not even a scratch. When I had that thought going over that they could not hit me and there was proof of it in five or ten minutes, this made me stronger than ever….

“I climbed up so as I could see and there was a German Captain lying there, badges on him and everything you could think of. Dead, you see. I looked down further and saw American uniforms–.” — USA vs Alvin O Monson, Ninth District Court #8237

In the official History of the 362nd Infantry, the scenes of battle were described in even more gruesome and terrible terms. The author wrote with blood-drenched words about the first shellings after the 91st went over the Argonne barbed wire and advanced through German territory:

“The men were like seasoned warriors, never hesitating in their advance, though their comrades on right and left might be hit by machine-gun bullets or mangled to pieces by shells. The less said about the effect of artillery shells on the human body the better. One minute there may be two or three specimens of perfect manhood, the next minute nothing but raw carcasses or groaning wounded with stumps for arms and legs.” (page 28)

Here are the descriptions from the official history’s Honor Roll of the deaths that Alvin described in this section:

STEARN, Joseph H., 1st Lt. MG. Co. Wounded in action Sept. 28, 1918. Died in Am. Hospital No. 114. Buried Sept 29, 1918, in cemetery back of hospital, Fleury.

GOODWIN (2259445) Hollis R., Pvt. 1st Cl. MG. Co. Killed in action Sept. 27, 1918, by H. E. [high explosive artillery] on the reverse slope of the hill just south of Epinonville, France. Buried Sept. 30, 1918 in cemetery No. 2 on Map Verdun Sil, point 75 Bg. 6 on right side Very-Epinonville road half way up Epinon hill. Grave No. 11.

SWIFT, Joseph H., 1st Lt. MG. Co. Killed in action Sept 29, 1918, by a sniper, at the edge of the woods near Gesnes, France. Buried Oct 7, 1918, north of Bois de Cierges de Tir 1/10,000 05.9-80.0

PIAZZOLA (2259477) Joseph, Pvt. MG. Co. Killed in action Sept. 29, 1918. Killed by a sniper while lying in edge of the woods preparatory to the attack on Gesnes, France. Buried Oct. 6, 1918, Bois de Cierges. Very 211 Granpre des Canevas de Tir 1/10,000 06.4-80.4. Grave No. 35.

WORSHAM, Elijah W., Capt M. G. Co. Killed in action Sept 29, 1918. Killed by a rifle bullet through the head on the hill overlooking Gesnes, France. Buried Oct 10, 1918, Map Very 211 05.4-81.0. Grave No. 1.

Alvin’s company regathered and then retreated, marching for almost a solid day. They pitched tents and ate the first real meal in more than a week. Two hours after they arrived, orders came for the 181st to return to the front. The company occupied a building to escape driving rain. At this point in his testimony Alvin began to waver. Eventually the judge was forced to adjourn for the day to let him regain his composure.

“I don’t know how long we were in there, but to look at the fellows and remember at first they had been such big husky fellows –. I will be all right in a minute. Well these big husky fellows, they looked just like skeletons. You would hardly recognize them…

“I got orders from the company Captain to go to Headquarters to bring up the mess. He said to bring up a hot lunch, see. I started back and walked, oh I guess, three miles… I had to follow a wire, a signal wire, see… I went over this hill and some German gunner spotted me and shot through the trees and I followed the wire down the hill. Then he started shooting good. I went down this hill and must have gone about a mile. I passed a bunch of fellows there and they had turned black. Dead soldiers. I saw them all over. I saw so many, I don’t know how many. And the smell was just something terrible.” — USA vs Alvin O Monson, Ninth District Court #8237

The judge asked Alvin to proceed. When he couldn’t, the judge and counsel conversed briefly and then Alvin was excused.

When his testimony resumed, Alvin told of his return to his company with hot soup. Then his tale took odd directions with no clear timeline. An anecdote about being positioned just in front of ten American artillery pieces that fired endlessly, “The effect it had on me was that I was crazy about.” A story about six men sleeping in a shack together that was pounded by shrapnel all night. In a longer story about fifteen men all sleeping in a shallow hole together he described being spotted by Germans with shells inching ever closer all night long. He supposed that they were gassed, and he passed out for four hours amidst the shelling. In the morning he looked out to see “big shell holes and all these fellows killed.”

It’s difficult to connect his stories to the 362nd’s record. Some of them must have been part of the 362nd’s assault on Gesnes, where they were the first American regiment to break through the third line of German defense (Kriemhilde line).

“At the moment set, the attack by the infantry was launched and the wild charge out across the open through a seething inferno began. Forward was the command received. What though it seemed to certain death! Not a man faltered or waited for another.

“The hills ahead fairly belched fire and the flash of artillery firing point-blank at the advancing waves could be distinctly seen. No man could describe the fury of the barrage that was poured down upon them. But, with shouts of ‘Powder River,’ they raced forward in thinning numbers through the storm of bullets, shrapnel, high explosives and gas shells, like wild men. The rapidity of the advance and the utter recklessness of the charge seemed to send fear into the heart of the Huns. They fled back over the hill leaving the wounded behind…

“Only a handful of men had emerged from the slaughter. Hundreds of dead and wounded were strewn over the battleground. Many officers were among the fallen… The burial party found the bodies of over 100 of our men in 200 yards… The moaning cries of the wounded seemed to come from everywhere out of the darkness. Here and there a man was found wandering about among the dead and wounded like a lost child; rendered so by the terrible shock and horror of the carnage… One company had eighteen men left of its 179.” — History of the 362nd Infantry

After describing rejoining his company again from another message run, Alvin recounted what it was like to have a shell explode nearby:

“We were stretched out on this bank. This shell came over our heads and hit about ten feet away. Well, I didn’t know anything, only this terrible pressure on my ears. I cannot explain it. It was something fierce. The whole company was strung along, see, but about eight men were all together, all talking to one another. It was a gas and shrapnel shell, commonly called ‘high explosive.’ And they ran up toward–. That explosion just forced your head back and forward. It made your head ache something terrible. I was going to tell you now,– it must have been a half an hour afterwards,– the men some ran to the left and some ran to the right and I just stayed right there. I could not move. I was alone,– I forgot to tell you, and I had dirt all over, dirt and everything. They were buried, but they got up. Some ran to the left and some ran to the right, but I could not move. I had to stay right there. Nobody was present when I came to. Maybe fifteen or twenty shells came in, kept coming higher and higher and after that I went and located the company, joined the company and marched up there where I said about the soup.” — USA vs Alvin O Monson, Ninth District Court #8237

The end of the Argonne campaign was as fractured in Alvin’s mind as the battles themselves. In the midst of describing the company all having dysentery he suddenly said, “We got on some trucks some place and went a little ways and then boarded a train –. This was on our way out of the Argonne, going up to Belgium.”

In Belgium the 91st Division, including the 362nd Infantry Regiment, relieved the 164th French Division and worked under the direction of King Albert of Belgium. Alvin spent the start of it in a hospital recovering from dysentery, and then rejoined his company for the last two weeks before Armistice. The official history calls this the “Battle of the Turnip Patches”, describing “geysers of dirt and turnips thrown up by bursting shells”. Likewise, Alvin’s testimony recounts sporadic shelling, repeated advances, and constant eating. He describes meals of potatoes, unnamed buckets of food (probably turnips), cheese, bread, tea, meat, and many more. It was a smorgasbord in comparison to the days of starvation and single description of grease and hard bread in Argonne.

Peace came suddenly, with the 362nd waiting to raid a town. The endless horror had lasted only a few months. They spent the next two months in bored, cold misery as they waited to return to the United States. After marching through Belgium and back into France they rode train freight cars again to St. Nazaire. There they boarded the troop ship USS Floridian for a trip back to Hoboken, New Jersey.

Home Sweet Home?

After arriving on in New York on April 15th, 1919, the 362nd was fractured. Men were sent to one of four camps nearest their home. Only two other men returned with Alvin to Camp Lewis in Washington. Alvin described his terror of the long train ride across the country, unable to sleep out of fear that an accident would happen. On May 5th they arrived in camp, and the next day Alvin was back in Seattle.

He was a dramatically changed man. In his testimony Alvin said it himself, “After I got back out of the Army, the war was all I talked about all the time. I talked war as soon as I got home.”

Mabel Olson, who worked at Groceteria in accounting, recalled in testimony that Alvin had no interest in the company or his friends or family when he returned. He was completely obsessed with his experience:

“He came in, threw his coat in the corner, and sat down, and just gave us the “hello” and started to relate of the war and experiences that would shock anybody, suggestive stories of back there in France, and he didn’t know any of the girls but myself; and I was disappointed… He didn’t ask about the business or anything, just talked war, war, war.” — USA vs Alvin O Monson, Ninth District Court #8237

Simple words or phrases would trigger flashbacks. The words “right” or “write” would remind him of Jack Wright, killed during the Gesnes assault by a bullet through the chest. But the flashback would be of Jack moving to a different train car just before the wreck. Advertisements for the popular refrigerator brand Copeland would remind him of a man killed in the train wreck. Other words like “me” or “knee” brought back other memories.

The Monson family decided it best for Alvin to rest and recover his weight. Alvin went to live with relatives in Chicago for a few weeks. Unfortunately he had to ride the elevated train to get around, and he passed out many times because his mind panicked.

The first work Alvin was assigned back in Seattle at the grocery chain was monitoring inventory to determine when to send product from the warehouse to each store. Repeatedly, Alvin could not focus on the task at hand because he would remember some personnel records he had been unable to keep in France and so he would begin a tally of wounded, killed, and men ready to fight.

Walter tried putting him in a variety of jobs including his old role as buyer, but the activity did not help Alvin as he hoped and it certainly did not help the company. Alvin suffered periodic back pains, migraine headaches, and memory flashes. He could not reliably do any work, needing to suddenly take hours or days off of work. To avoid the banter of selling agents Alvin would simply arrange to buy vast quantities of unneeded materials at ridiculously high prices.

Alvin went to doctors for minor issues, but he avoided seeing a Veterans Administration doctor about his PTSD for twenty years. By the time he realized he needed help the government was unwilling to pay. It took a lawsuit to secure payment. The transcript of that case has left us with an amazing record of a man, an idea and how it can be ruined by unexpected war. After he won the lawsuit his life wasn’t magically better. He continued living on a rural farm in Snohomish County with his brothers and mother, his mind enraptured by a few months of war.

A Note on Sources

A variety of primary sources allowed this article to be written. First and foremost, the transcript of Alvin Monson’s 1934 lawsuit against the Veteran’s Administration to receive disability pay. The text is poignant and chilling at times, while also providing insights into Monson’s past and his company Groceteria that allowed me to write the history of that chain grocery store. There were many moments where Alvin broke down during the testimony, each captured with a simple “(witness weeps)” , “(weeping)” or similar comment.

After World War One each unit created its own unique history. The 91st Division was given an overarching history. Also the 362nd and its sibling the 361st Infantry Regiment had their own histories, which are quite surprising in contrast. The 361st is thorough in detail, perhaps even clinical in describing troop movements and exact times and locations. The 362nd’s story is grisly, chaotic and disturbing despite attempts to highlight the patriotism and bravery of its men.

The Seattle Times archive served me as it always does.

For additional information about the 361st, HistoryLink has a good article by Duane Denfeld in 2014 focused on that regiment and tying it to the overall story of the 91st Division.

Finally, the fine master’s thesis of Bryan Woodcock, The 91st Infantry in World War I, is worth a long read. He takes the first steps to plug the gap in historical review of the division.

Additional Materials

Update December 2017: While preparing for the KNKX interview I made a new discovery.

I made contact with the descendant of a relative of Alvin Monson, who had two photos of him. They both show him happy and in uniform. They must date from Spring of 1918, before he was sent to France.

Further Reading

For more about Alvin Monson, please read my articles and interviews:

- Groceteria

- The grocery revolution reaches Broadway (CHS)

- Piggly Wiggly on Broadway (CHS)

- This man invented self-service grocery (KNKX) Radio interview. Small quibble: he brought discount groceries to Seattle.

My other war related writing:

- Mapping Seattle and the Forgotten War, in which I find the homes of each Korean War KIA in Seattle

- Seattle’s second Seafair, photos of a troop transport arriving back home

- Seattle’s first Korean War parade, describing the return of veterans

- Waning days of One woman’s war, about a woman who served in Seattle during World War Two

- Wolf Cubs lost at war, part of a series about the beginning of Cub Scouts and telling the stories of a group that died in World War Two

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hello,

I have been researching our American Legion John “Jack” Henry Post #1’s history. It is named for a WWI Veteran. He was a Pvt M. C. G., 362nd Inf 91 Division. He was born in Minnesota but was registered in Anchorage, Alaska when he entered service.

The namesake of our Post is John “Jack” Henry who was killed in action Sept 29, 1918 at Boise de Cierges; buried October 8, 1918 in American cemetery Gesnse.

Another description of his death says Map Very 211 Granpre de Caneves de Tir 1/10,000 05.9-80.6 Grave No. 8.

Very is a small village in the Argonne, north-east of Varennes.

I am wondering if he would have been along with Monson, at least getting to France. Where would I find information about getting from Alaska to Washington at that time?

Thanks for your article, Jeanne

I sent this in email to Jeanne last month, but will post it here as well in case someone else finds it useful:

Hi Jeanne, thank you for the comment on my Alvin Monson article. I’m glad it was useful to you.

It does appear that Alvin Monson’s history should directly apply to John Henry. Henry was in the machine gun company with Monson, so would have also been on the same train that was wrecked.

The only thing I would suggest confirming is the exact service record of Henry. Men were sometimes moved between groups to bolster ranks. That is, just because he died in the 362nd machine gun company does not necessarily mean he started the war there. For Washington state I know how to find the records, but not Alaska. I suspect you do. If you need help decoding the shorthand of the service records let me know. I’m not an expert but I’ve done it several times recently.

The burial at Very would have been a temporary grave after the battle. Men were often buried this way and then moved to larger permanent graves as time allowed or after the war.

I’m not sure if there is an Alaska listing or if he is considered a Minnesotan in the photos of fallen soldiers, but you should find him in these,

Volume I – Alabama through Maryland, http://books.google.com/books?id=dswMAAAAYAAJ

Volume 2 – Massachusetts through Ohio, http://books.google.com/books?id=vcwMAAAAYAAJ

Volume 3 – Oklahoma through Wyoming, supplement (miscellaneous photos) and foreign soldiers, http://books.google.com/books?id=-MwMAAAAYAAJ

I believe you found this already. John K Henry’s death is listed on page 62 of the 361st history, https://archive.org/stream/historyof362ndin00meldrich#page/62/mode/2up/search/henry

In that same book on page 34 is the description of September 29th.

Sincerely,

Rob

Hello: My grandfather served in Headquarters Company 362nd during WW1. He was on a 37mm gun crew. Last July, my father, son and myself took a trip to France and followed the rout of the 362nd. This included visiting Gesnes and the cemetery. Even tracked down the grave of of grandfather’s Platoon leader. Then went to Belguim and finally to the Bonneiers train crash site. Was a very interesting trip. Jeff

Jeffery, thank you for the comment. Have you posted any of the photographs or memories online? I would love to see them.

Was your grandfather in the machine gun company? And, by any chance, do you have photographs of him from the war?

[…] of his infantry unit’s arrival in Europe, Monson was involved in one of history’s most gruesome train wrecks, in which 30 soldiers were killed and over 50 wounded. Shortly after the accident, the remains of […]