We segue from a nearly-forgotten use of a nearly-forgotten building, to final memories of a veteran.

Mixing old and new

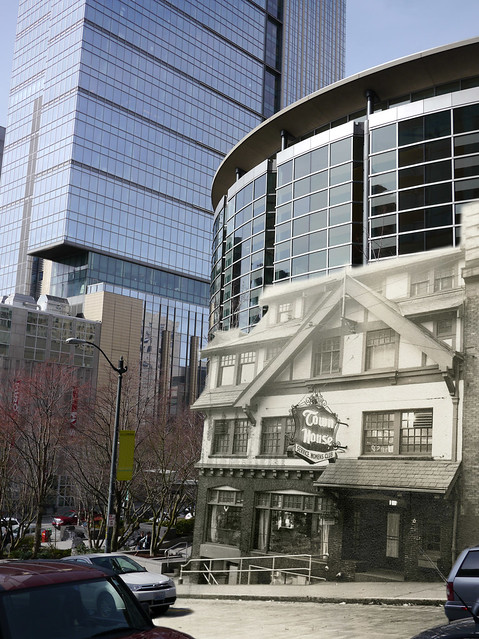

The structure would have been a good candidate for my book Lost Seattle if I had these photographs last year. In my description of the collapse of Washington Mutual I included a photograph taken just down the street, but I had no idea that such an interesting building existed on University Street right in the middle of downtown.

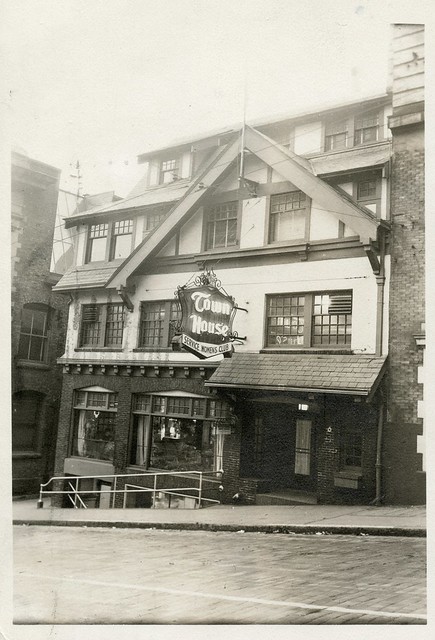

This mixed-use Tudor was built in 1914. As described in a 2012 installment of Paul Dorpat’s Now & Then, it opened as the Northold Inn, and was already stylistically as out of place as it would be today. Upstairs were apartments and downstairs was a traditional English restaurant, run by the proprietor of a department store tea room.

To fit into his column’s word count, Paul kept the building’s history brief. As you can see in our blend, the Northold Inn has now been replaced by Benaroya Hall. Paul Dorpat skipped over some of the reason for that, which we can fill in.

I remember the afterwards

My first memory of this site was the summer of 1993. The entire block was an empty crater except a hole right in the middle, entered from Second Avenue. I’d pass the threshold and head down to the platform of Metro’s bus tunnel to head to my job at the old Bellevue Uwajimaya. Metro had used the block as a staging area during tunnel construction, leaving it a wasteland until Benaroya Hall was finally constructed in 1998.

Several Seattle Times articles in early 1988 described efforts by Allied Arts to save the old Northold. They came to a close with an April 8 editorial: “This isn’t [an editorial about] the four-story frame building that, as a Tudor chalet more than 50 years old, may have been unlike anything else in downtown in America. The reason we are not writing about 214 University and the other buildings is because they are not there… They’re matchsticks, piled high. They lost to money and clout… The empty lot is owned by Marathon U.S. Realties, which cleared it as part of a lease agreement with Metro… I have put their names in the paper today so that, as Seattle moves forward, you know… whom to fear.”

So it was demolished to make way for a massive public works project, the tunnel that now runs light rail to SeaTac and commuter buses to the suburbs.

Service Women’s Club

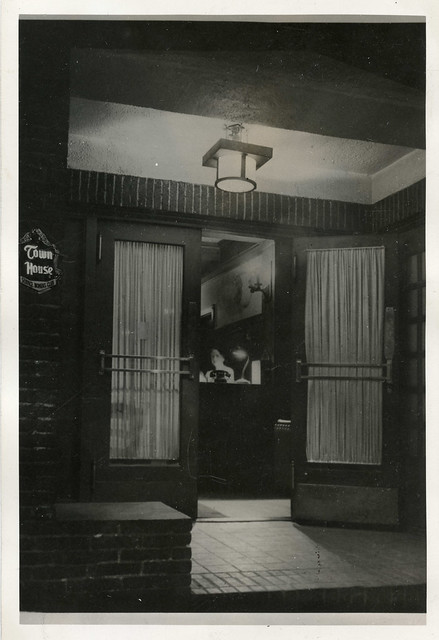

Paul Dorpat’s article also only briefly mentioned the building’s use as a “USO dormitory” during World War Two and skipped the prior use. In Paul’s old 1937 photo the commercial space was empty. In our 1946 photo it said “Town House – Service Women’s Club”. In the interim, the Seattle Union Gospel Mission moved its employment and emergency support services for women into the building in 1940, perhaps using the upstairs apartments for housing women and basement as office space. In 1941 the main floor restaurant was taken over by the Town House card and lunch room.

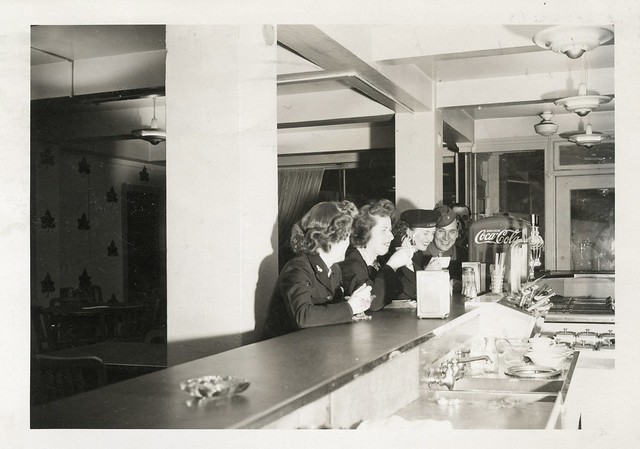

As a HistoryLink article describes, a number of lounge, entertainment and temporary stay facilities were operated for use by military personnel during World War Two. As they expanded they became specialized. A facility for female officers was opened by the Seattle Officers Club on First Hill in January 1945. Meanwhile Dorothy Stimson Bullitt was leading a campaign to create a club for enlisted women. That lead to the April 2nd dedication of the Seattle Service Women’s Club in the former Town House and Union Gospel Mission space.

Laura Burnham

These photographs are from the backs of postcards sent by Laura Burnham to her mother in Vermont in January 1946. The war had been over for 5 months, but Laura’s service to her country was not over.

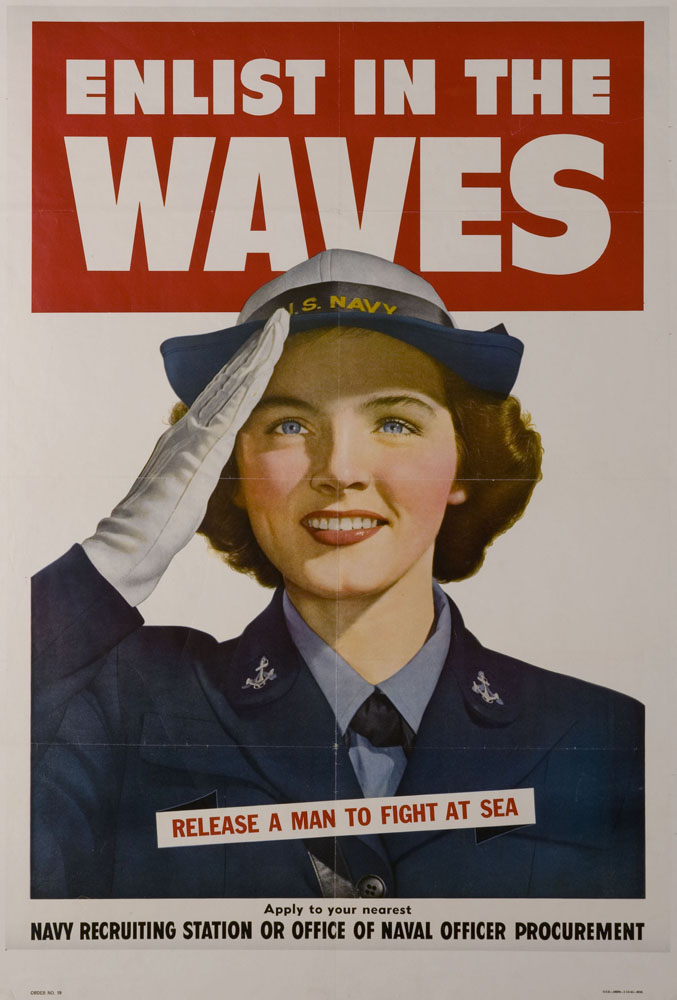

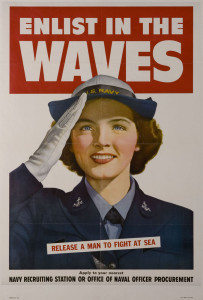

In her return address she describes herself as “Ph M 3/c”. This is a Navy rank of Pharmacist Mate 3rd Class. In some contexts that means a medic, but Laura probably worked at a base hospital. [I have since learned that she worked at the naval hospital in north Seattle that later became the new home to Firland.] Her address is written “Waves Bks A, Pier 91”. That’s Barracks A at the Navy supply depot in Seattle’s Smith Cove. The massive pier was renumbered from Pier 41 to Pier 91 during the war, and today serves cruise ships.

“Waves” stands for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, the name of the Navy’s women’s corps. At Smith Cove women made up a third of the workforce. WAVES had two barracks and an officers’ quarters on a shoulder of Magnolia Bluff raised above the reclaimed land of the depot. Today it’s Smith Cove Park play fields. Back then they had beautifully furnished lounges and their own laundry facilities. In the basement was a beauty parlor created by Broadway High graduate Edgar Lee Smith. He traveled from base to base setting them up and finding sailors with hidden hair stylist skills who were willing to reveal their talents for the bounty of liquor that dry nurses would barter with them.

I’m not sure exactly what Laura Burnham was doing in Seattle in 1946. Other women were being transferred through Seattle on their way to discharge because the war was won. The text on Laura’s postcards makes me think that’s the case: “Hi Mom – This is that wonderful Service Women’s Center I’ve told you so much about. Isn’t it nice?” If she’d been stationed in Seattle permanently, I’d expect that message to be sent in the spring or summer, soon after the club opened.

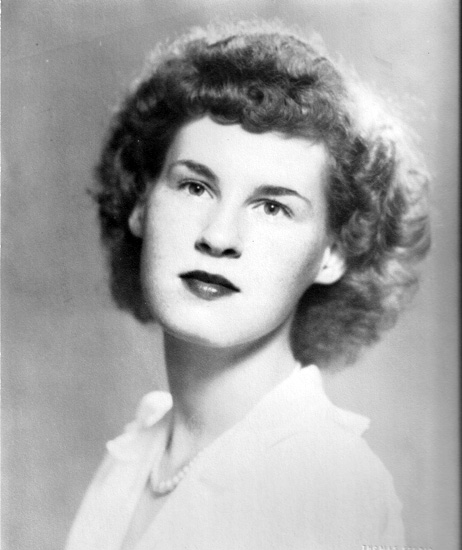

The end of Laura Clementsen’s life

It took some digging for me to piece together Laura’s life because she married after the war. After successfully landing some genealogy gymnastics I ended up at a sad place. Laura died a week after I purchased the postcards that she sent, on February 27, 2014. I’ll let you read about her in her family’s own words, or the memorial by the local paper where she wrote editorials. For the purposes of our tale, it’s fun to see that she was promoted again to Ph M 2/C before her discharge. I hope I will be remembered with even a sliver of the words that were left for Laura: “Clementsen was a lifelong student of the world. She was a voracious reader of current events and philosophy, religion, women and human rights, world history, travel and more.”

Here’s a photo of Laura taken from her family’s memorial site. I imagine her in uniform, leaving the beauty salon, ready to spend another day helping injured and sick sailors.

Perhaps you’ll join me in taking up her family’s suggestion to donate in her memory to Planned Parenthood of Southern New England. Thank you Laura for your service, and for leaving these remnants of Seattle for me to find and share.

UPDATE 1

I received the following, fantastic photograph via Twitter:

UPDATE 2, 8/6/2014

After exchanging email with Joy, I found that she had taken responsibility for Laura’s estate. Joy sent me a number of photos, newspaper clippings and other records related to Laura’s WAVES service. These were accepted along with my postcards by Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry to help tell the story of wartime Seattle during WW2. The are accessioned as 2014.84.1 to 2014.84.15.

Joy is in the process of donating other material including Laura’s extensive research on octagon houses in New England. So far material will be split between the Cheshire Historical Society and New Haven Museum, in addition to the material already at MOHAI.

Further Reading

- Seattle’s second Seafair, photos of a troop transport arriving back home

- Seattle’s first Korean War parade, describing the return of veterans

- Man as oversimplified data, a critique of errors in the historical record

- Mapping Seattle and the Forgotten War, in which I find the homes of each Korean War KIA in Seattle

- Wolf Cubs lost at war, part of a series about the beginning of Cub Scouts and telling the stories of a group that died in World War Two

- (Witness weeps) – the tragedy of Alvin Monson, part of a series about early grocery history telling of a shell shocked businessman in World War One

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.