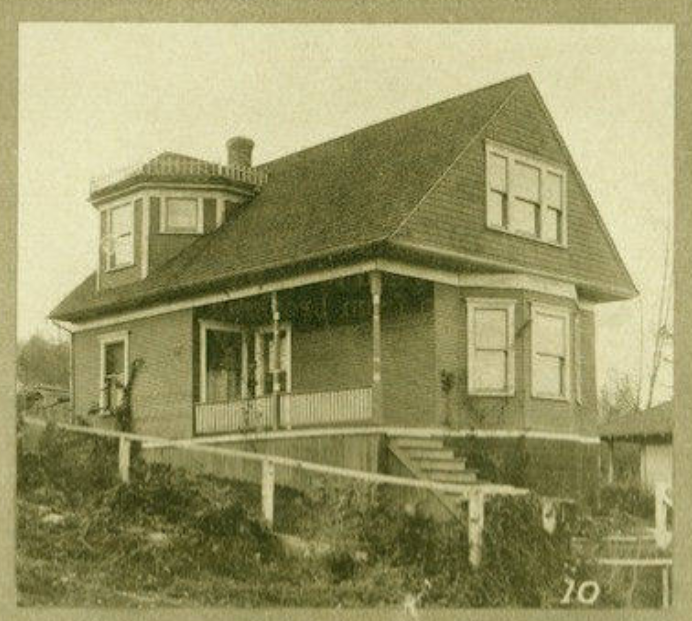

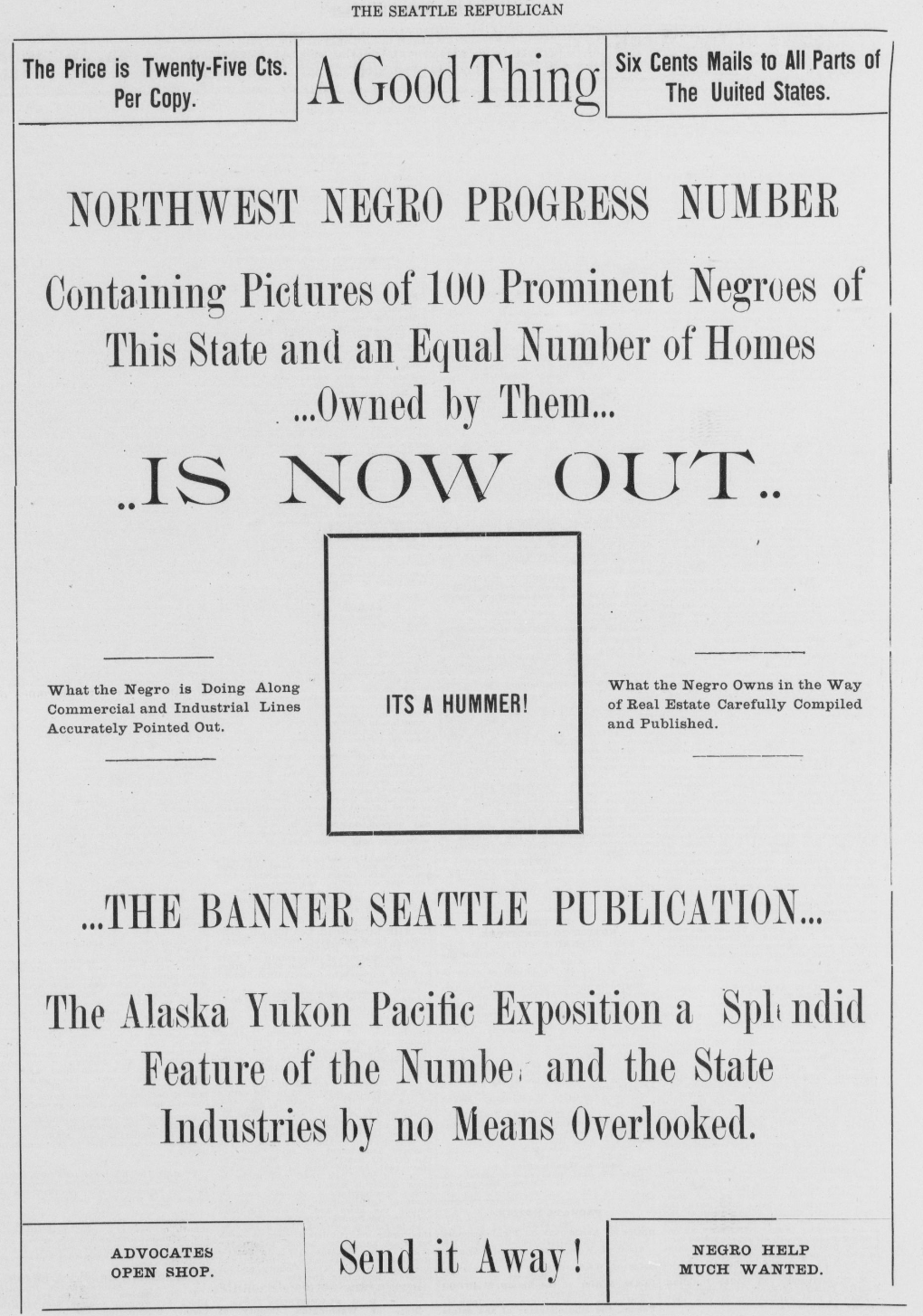

In early 1909, a special edition of the Seattle Republican newspaper titled “Northwest Negro Progress Number” profiled Seattle’s Black families’ homes. It was promotional material in the lead-up to the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exhibition. In addition to profiles of members of the Black community and descriptions of opportunities for newcomers, the magazine included photographs of 32 homes and buildings owned by Black families.

Seattle’s Black families’ homes, photographed

The digitized Northwest Negro Progress Number is available via the Washington Women’s History Consortium and Washington State Historical Society. In the pamphlet, photographs begin on page 33.

| First and Middle | Last Name | Address | House exists still? | House Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John C | Robinson | 519 27th Ave S | No | Street gone, removed when MLK put in. House gone. Townhouses. |

| B J | Angelle | 8825 2nd Ave S | No | |

| Fred | Mitchell | 607 N 51st | No | Replaced with new house in 1960. |

| Sarah | Grose | 1729 24th Ave | Yes | Home still there. Now 1733 |

| Aurora E | Grose | 1703 24th Ave | No | Replaced by YMCA |

| George | Selby | 2608 e valley st | No | replaced by new home. |

| W H | Teemar | 2633 e valley st | Yes | second story added on top, but looks like same base; built ca 1906 |

| Thomas | McPherson | 4506 Holly St | Yes | Possibly 4508 S Holly St; with roof remodeled |

| J S | Murray | 611 27th Ave E? | No | The caption makes it sound like it is a rental property. |

| H G | Jones | 825 29th Ave | Yes | Greatly changed; supposedly built 1908. Yard lowered later. |

| E | Hayes | 2600 e valley | Yes | |

| Calvin | Rhodes | 1700 25th Ave S | Yes | He lived at 1708, but this looks just like 1700. |

| W M | Wylie | 2608 E Thomas | No | Demolished and replaced by a 4-plex with 2606 in 1989 |

| R | Turner | 1628 Boren Ave | No | Might match 1904 Sanborn (not present in 1912 Baist) |

| Walter | Washington | 209 30th Ave E | Yes | Current house dated 1920, but could be wrong. 1936 aerial might match. Heavily altered. |

| Richard | Johnson | 1714 25th Ave S | Yes | Porch altered |

| C H | Harvey | 308 29th Ave E | No | demolished, 1984. |

| W H | Henderson | 607 22nd Ave | No | demolished, replaced 1984. |

| J T | Gayton | 436 26th Ave E | No | demolished… was a church, also demolished, home under construction |

| R A | Clark | 111 25th Ave E | No | This address is empty in 1912. -- demolished |

| I F | Norris | 535 Federal Ave E | Yes | |

| Z L | Woodson | 1510 12th Ave | No | Demolished 2014 |

| G W | Turner | 1735 25th Ave | No | demolished or heavily altered via remodels |

| Z L | Woodson | unsure | unsure | Is this 1820 24th?? |

| George | Maney | 2209 S Lane St | No | demolished |

| Green | Fields | 1924 1st Ave W | No | demolished; McClure Elementary |

| Frank | Smith | 416 19th E | No | demolished, but still there in 2011 street view. |

| Z L | Woodson | no idea | Unknown | |

| J G | Gayles | 323 21st | No | House demolished <1999. Neighboring home visible. |

| Edward | Hawkins | 201 Queen Anne Ave N | No | demolished |

| L P | Ray | 2306 N 77th St | Yes | Blurred in Google SV. Long description of construction in autobiography: https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/rayemma/rayemma.html |

| Susie Revels | Cayton | 518 14th Ave E | Yes |

You can view the list (minus Z. L. Woodson’s as-yet unknown properties) on a map in Google, with an embedded data table.

Progress to lose

A heading on the first page of the Northwest Negro Progress Number cried out “Come West, Black Man”. After that, examples of successful Black men and women filled its 80 pages, along with details about Seattle and the Northwest.

Although their newspaper readers in Seattle stretched beyond the Black community, owners Horace and Susie Revels Cayton explicitly targeted the Black community in other cities with NNPN. They described the opportunities for jobs, successful businesses, and happiness in a Seattle environment that they promoted as not racist, and not anti-Black people. The result should have been a booming sales pitch for Seattle.

The Caytons’ endorsement of Seattle was circumspect, though.

They gave it credit, “No section of the whole United States offers such an inviting field for the brawn of the Negro as the far Northwest.” But then they put huge caveats on that. Their more nuanced argument was that Black people should leave the South and spread out in smaller numbers around the country, to avoid panicking white people:

“So long as the black folk are not sufficiently numerous to cause alarm in the minds of white folk that their presence in the community might mean ‘[N-word] dominancy’, there will be little or no strife between the whites and the blacks, but where there is a danger of such, perpetual strife does and will prevail, judging from the past, the black man always comes out at the lower end of the rope.”

Northwest Negro Progress Number, page 7 (Seattle Republican Vol XIV, No 1)

In essence they said: Come to Seattle and earn a living. Sure, they don’t love you. But they also don’t hate you, just as long as you don’t make yourself noticeable. If you do, we’ll all be back at the bottom of a gallows.

Surely there has never been such a disheartening counter-argument and rebuttal as this in civic promotional marketing.

Jobs, but only for hundreds

After a long explanation of the opportunity for non-unionized labor and domestic work, the Caytons delivered their final pitch:

“Let’s hope that hundreds of black folk tired of the everlasting warfare between themselves and the whites in the South where they are badly congested will take the advice of Horace Greely and ‘Come West,’ if not to grow up with the country to fill a long-felt want… Do not get the idea in your head that counting house jobs, high official positions and clerical job as in general await your coming, for they do not and it’s only in isolated cases that a black person gets one of those.”

NNPN, page 8

Just “hundreds.” Seattle, with a population of around 200,000 in 1907, could only absorb a few hundred more Black people before the white majority would get anxious, as the Caytons told readers.

This ambivalent call showed the perilous state of the Black community in Seattle at the start of the 1900s. Moreover, it illustrated that they were never in positions of power, and that they were subject to the whims of those who wielded it.

Among the dozens of profiles in the NNPN, there were some individuals who challenged this characterization. In Seattle there were lawyers Andrew R. Black, J. Edward Hawkins, and A. G. Harrison. Another example was Dr. David T. Cardwell, who graduated from Biddle and then got his MD from Howard, and was a practicing surgeon.

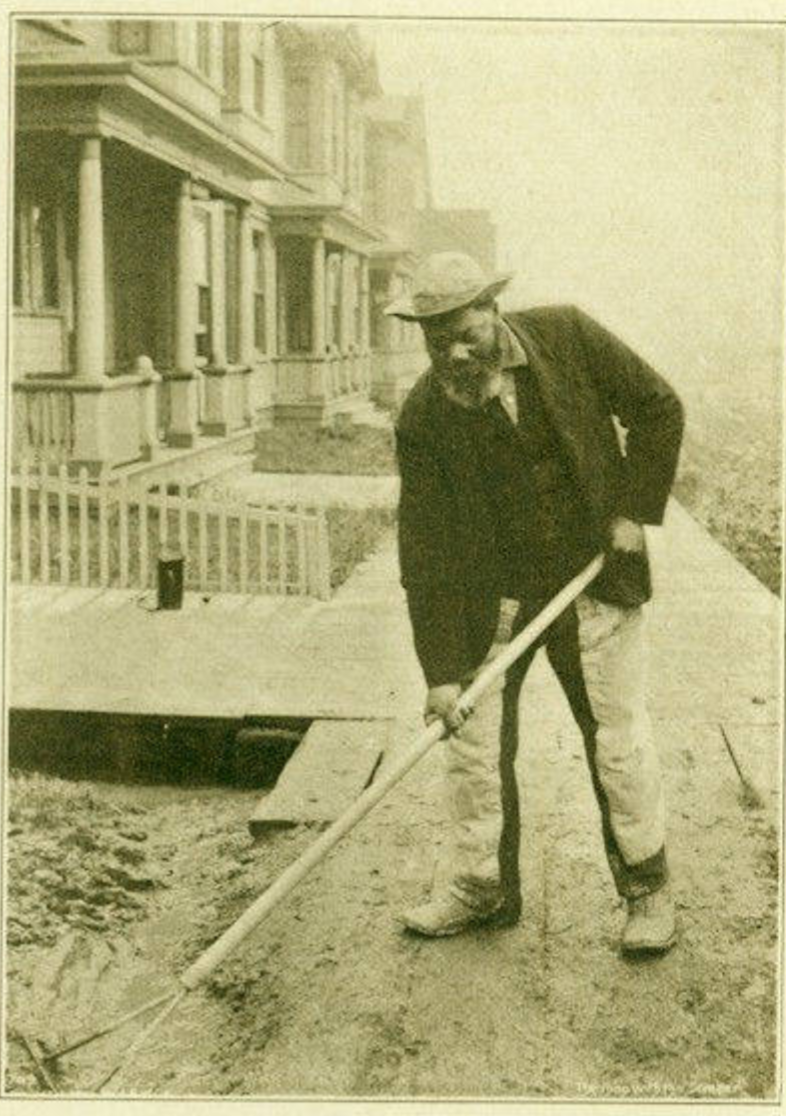

But besides them and a group of pastors, the others profiled had professions that conformed to expectations: waiters, messengers, barbers, and restauranteurs.

Indeed, while under a “Help Wanted” heading in NNPN the Caytons listed general descriptions of many jobs to be had, none were as ceiling-pushing as doctor or lawyer. The jobs held by Black men in Seattle that they listed were:

- 25 employees of the gas company

- 25 employees of Seattle street cleaning department

- one policeman

- a dogcatcher and head of city pound

- 75 employees of various hotels: three hotels with waiters and two with bell boys

- eight plasters, “several” brick masons, “half a dozen or more” carpenters, and four painters

- 30 hod carriers (brick carriers) and mortarers

- “a large number” working at asphalt companies

- “hundreds in other employment”, a catchall including porters, janitors, watchmen, firemen (men who put coal on fires for boilers), coachmen, and cooks.

Possibilities for all of Seattle’s Black families

Horace and Susie Bevels Cayton published their initial showcase of homes in 1907. Then, several times in 1908, they reused those photographs to discuss homeownership. In 1909, the entire Northwest Progress Number was reprinted.

Each time, they emphasized that homeownership was a possibility for every Black family in Seattle. Through hard work and savings, they argued, a single adult or couple could expect to own a modest home that they could enliven with joy and décor.

In one of those 1908 articles, they were able to further illustrate their point with a contrast to a recent high-profile article. In May 1908, Booker T. Washington wrote “Negro Homes” for Century magazine. Like the Caytons, Washington included photographs of many homes owned by Black people. But the Caytons pointed out that the photographs were all “of the stars of the race” that a regular person could not aspire to: large, well architected homes on spacious land.

The Caytons cautioned that only six Black men in Seattle were professionals. And so it was unreasonable to provide such homes as models. “Only in rare instances will you find such commodious homes among the Seattle Negroes as those represented by Prof. Washington, but all of them have pleasant homes and they are for the most part well cared for.”

The Caytons’ desire to profile normal homes actually was harmonious with Washington’s article. He began by characterizing the shift from slave quarters in the South to “neat and comfortable farmers’ cottages”. In Southern cities he described a transition from “wrecked hovels” to “modest cottages… [with] a wholesome air of comfort and thrift”.

Washington’s point was that there was yet another class of buildings, “larger and more comforable… with all the taste and culture that you might expect” in many cities of the South. The Caytons sensed potential conflict with the white elite in Seattle, and few opportunities for work for migrants of the professional class. Instead, they expressly reached out to laborers, porters, waiters, and restauranteurs.

Cayton’s call to “Come West, Black Man” apparently worked. After 18 months of NNPN’s initial run, Seattle’s population of Black people increased to an estimated 3000 at the start of 1909, up 500 during 1908. (see I. I. Walker, 1/2/1909 Seattle Times)

Solving racism: homeownership as citizenship

In 1906 the Caytons shared a Spokane Spokesman-Review summary of Harry Stillwell Edwards’ article “The Negro and the South,” which appeared in Century Magazine. Edwards illustrated a case for Black homeownership after his return visit to the Black community of Macon, Georgia in 1903. He previously visited there in the 1880s, when people were still struggling to make a living after the end of slavery.

“The community is on the high-road to a better civilization, because the male members command a higher scale of wages, and because they have become home-owners. And they command higher wages partly because the country is prosperous, but mainly because education has opened up to them a pathway for ideas and taught them to observe and think. For it may be stated as a fundamental that progress ever travels on ideas and abject poverty is embalmed in ignorance…”

“The happiness of home-owning strikes the American negro with particular force. The centuries have taught him that the people who command respect are the owners of lands and homes; and once in his own home, the home itself begins to teach him higher things. The home at once demands to be made attractive. It demands respect not only from its occupants, but from its neighbors. It demands safety from invasions. It takes on a sanctity that extends to every member of the family, and decent living is the rule… It has become the home of a self-respecting American citizen.”

“And having secured for himself a permanent home, the possessor adds himself to the higher class and demands that the public around him share the respect he feels for himself. Moreover he becomes amenable to the reasons which sway all other home-owners. He sees the force of arguments for low taxation, good streets, adequate police service, quick transportation, and fire departments. And seeing so much, he eventually learns that his ballot must neither be suppressed nor sold.”

Edwards, Harry Stillwell “The Negro and the South”, Century Magazine, 1906

Edwards’ article frames the idea of Black homeownership in important terms. The Caytons’ call to “Come West, Black Man” did not simply beckon individuals to personal success. On the contrary, it called on an entire generation to more completely realize freedom, liberty, and emancipation.

Unresolved racism: homeownership as invasion

Seen from today’s lens, though, Edwards’ article was problematic. It came from a segregationist perspective, characterizing Black families’ homes as expected to be separated from white families’.

The Caytons recognized the problems that racists caused for Black families who simply purchased a home wherever they liked. For example, when describing J. H. Doage’s home in Tacoma, they said, “His home is situated in a nice neighborhood, and he sees to it that it is kept looking just as well if not better than those of his neighbors, because he knows if he does not, his neighbors will be complaining about that ‘[N-word]’s shack on the corner.'”

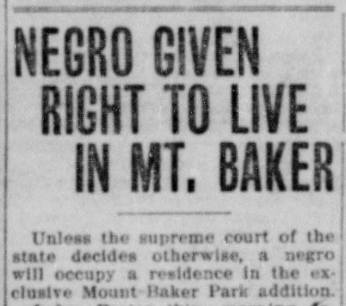

Indeed, the Caytons became victims of racism themselves in 1909. Seattle real estate broker Daniel Jones perversely sued them in April, claiming that their skin color was lowering home values. Jones didn’t even live in the neighborhood, though. Instead, his home was at the intersection of Broadway, James, and Minor, across the street from Castlemount, the Haller mansion. And 1909 was an oddity for him: Jones lived in hotels or the Rainier Club for most of his thirty years in Seattle.

Jones cared about the Caytons’ presence because he was a real estate broker. So he wasn’t personally affected, but was still willing to trade their happiness for money. He thought he could make more money selling property and houses at a higher price if there were no Black people living in the neighborhood. Later, Jones did the same thing in Mount Baker Park, which he developed as owner of the Hunter Tract Investment Company. There, he tried to stop Susie and Samuel Stone, and separately David Cole, from purchasing land and building homes.

Jones lost each of these lawsuits, against the Caytons, Stones, and Cole. The lawsuits came in rapid succession over ten months from 1909 to 1910. But was that the first time Jones took action as a segregationist and racist? And was it the last? Jones deserves a long look to consider what other racist actions he took as a real estate developer and city leader. As a broker, he bought and sold real estate during a long arc of Seattle’s rapid growth from 1888 to 1920. And these weren’t just scattered, single properties. At the other extreme, Jones owned or was primary sales agent for at least 15 different additions to Seattle, meaning that he controlled the original purchasers in 15 neighborhoods.

Daniel Jones partnered with the pioneer Phinney family for his entire career. In 1889 he built the Butler Block with Guy Phinney. In the 1890s he coordinated the sale of Woodland Park to the City of Seattle. For two decades he coordinated sales at Phinney family additions. And he partnered with son Arthur as Jones & Phinney at the end of his career.

Jones & Phinney developed the Carleton Park addition in Magnolia starting in 1919. Jones may have learned the wrong lesson in Mount Baker Park. Per newspaper articles, he included restrictive language in deeds. Racial restrictions may have been on the list, to preclude resale to a non-white person. Deeds have been found from 1928 with language excluding buyers of Asian or African descent.

“No person or persons of Asiatic, African or Negro blood, lineage, or extraction shall be permitted to occupy a portion of said property, or any building thereon; except domestic servants may actually and in good faith be employed by white occupants of such premises.”

Carleton Park Addition, per UW’s Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project

Those covenants spiraled through Seattle developments, and in the late 1920s transitioned to also include covenants signed by existing homeowners. Indeed, one eventually came to restrict the area around the Caytons’ former Capitol Hill home.

Jones lost his court cases in 1909. But he and his segregationist colleagues dictated homeownership for Seattle’s Black families for decades.

Additional Seattle Black families’ homes

In the October 2nd, 1908 Seattle Republican, the Caytons included a longer list of Black residents of Seattle that owned homes or buildings. That list is combined here with the 30 people from NNPN. Please feel free to send an email or leave a comment with any information you already have about these people and where they lived.

| Title | First | Middle | Last | Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W. | L. | Presto | ||

| Ben | Williams | |||

| W. | E. | Bennett | ||

| Benjamin | L. | Franklin | 1834 27th Av | |

| C. | H. | Harvey | ||

| J. | H. | Booker | ||

| Mrs | Frank | Marguson | ||

| F. | W. | Green | ||

| G. | W. | Thompson | ||

| Mrs. | W. | Taylor | ||

| Mrs | Eliza | Sheperd | ||

| Mrs | King | |||

| Mrs | Scott | |||

| W. | H. | Teemer | ||

| Maurice | O'Brien | |||

| Mrs. | Carrie | Selby | ||

| Samuel | P. | De Bow | 424 19th Ave E | |

| William | Creasman | 1014 31st Ave E | ||

| Mrs. | Mattie | Agee | ||

| Preston | Brown | 2614 E Madison St | ||

| George | Rowell | |||

| James | Allen | |||

| Mrs. | Miller | |||

| Frank | Anderson | |||

| C. | Brayshere | |||

| R. | W. | Butler | ||

| Joe | Moss | |||

| George | Bailey | 1023 S Holden St. | ||

| Will | Bailey | 1023 S Holden St. | ||

| Mrs | Bailey | |||

| Ben | Sellers | |||

| Mrs. | Jackson | |||

| J. | L. | Percy | ||

| Charles | Curry | |||

| W. | R. | Gamble | ||

| Ransom | Hutt | |||

| Eugene | V. | Galloway | 4209 S Orcas St. | |

| Marshall | C. | Calhoun | 4259 S Orcas St. | |

| S. | E. | Williams | ||

| James | Anderson | |||

| Milton | Roy | |||

| Peter | Clinch | |||

| Thomas | Payne | |||

| A. | J. | Jennings | ||

| W. | M. | Weathers | ||

| Mrs | Annie | Finny | ||

| Charles | Sims | |||

| W. | B. | Davis | ||

| Mrs. | E. | L. | Whitner | |

| Mrs. | S. | A. | Richardson | |

| Fred | Mitchell | |||

| J. | E. | Hawkins | ||

| J. | A. | Williams | ||

| M. | J. | Combs | ||

| Andrew | R. | Black | ||

| Thomas | McPherson | |||

| Mrs. | R. | Johnson | ||

| Calvin | Rhodes | |||

| Samuel | Turner | |||

| James | Allen | |||

| P. | E. | Ory | ||

| J. | Austin | |||

| Mrs. | Lovey | |||

| H. | G. | Jones | ||

| W. | H. | Henderson | ||

| A. | H. | Hall | ||

| J. | T. | Bailey | ||

| Jason | G. | Gayles | 323 21st St. | |

| Mrs. | A | Lawrence | ||

| Richard | Davis | |||

| B. | F. | Tutt | ||

| Mrs. | G. | S. | Bailey | |

| Mrs. | M. | B. | Mason | |

| C. | T. | White | ||

| John | Gibson | |||

| M. | J. | Shockley | ||

| Willis | Berry | |||

| William | Blockley | 1503 14th Ave S | ||

| Caroline | Campbell | |||

| J. | Bird | |||

| Barabara | Davis | |||

| Rev. | George | Manney | ||

| Mr. | Lavender | |||

| Mrs. | K. | Corum | ||

| Clark | Harris | 2619 W Lynn St | ||

| Mr. | Brewster | |||

| W. | C. | McClinton | ||

| Mr. | Prayto | |||

| Samuel | Thorn | |||

| Stephen | A. | Glass | 1619 N 51st St | |

| Hiram | Campbell | |||

| Mrs. | Wallace | |||

| Mrs. | Foster | |||

| M. | T. | Coma | ||

| W. | James | |||

| J. | P. | Ball | ||

| F. | N. | Harris | ||

| George | O. | Allen | ||

| William | M. J. | Wylie | ||

| Mrs. | Lillian | Wylie | ||

| J. | N. | Drake | 611 26th Ave E | |

| G. | E. | Hayes | 1617 Broadway E | |

| Henry | Gregg | 244 E Ahola St | ||

| John | C. | Robinson | 519 27th Ave S |

|

| Benjamin | J. | Angelle | 8825 2nd Ave S | |

| Fred | Mitchell | 607 N 51st | ||

| Sarah | Grose | 1729 24th Ave | ||

| Aurora | E. | Grose | 1703 24th Ave | |

| George | Selby | 2608 E Valley St | ||

| W. | H. | Teemar | 2633 E Valley St | |

| Thomas | McPherson | 4506 Holly St | ||

| James | S. | Murray | 611 27th Ave E | |

| Henry | G. | Jones | 825 29th Ave S | |

| Esther | Hayes | 2600 E Valley | ||

| Calvin | Rhodes | 1700 25th Ave S | ||

| W. | M. | Wylie | 2608 E Thomas | |

| Robert | J. | Turner | 1628 Boren Ave | |

| Walter | C. | Washington | 209 30th Ave E | |

| Richard | Johnson | 1714 25th Ave S | ||

| Charles | H. | Harvey | 308 29th Ave E | |

| William | H. | Henderson | 607 22nd Ave | |

| John | T. | Gayton | 436 26th Ave E | |

| R. | A. | Clark | 111 25th Ave E | |

| Isham | F. | Norris | 535 Federal Ave E | |

| Z. | L. | Woodson | 1510 12th Ave | |

| G. | W. | Turner | 1735 25th Ave | |

| Z. | L. | Woodson | ||

| George | Maney | 2209 S Lane St | ||

| Green | Fields | 1924 1st Ave W | ||

| Frank | Smith | 416 19th E | ||

| Z. | L. | Woodson | ||

| J. | G. | Gayles | 323 21st | |

| Edward | Hawkins | 201 Queen Anne Ave N | ||

| L. | P. | Ray | 2306 N 77th St | |

| Susie | Revels | Cayton | 518 14th Ave E |

Postnote

This article is based on the Caytons’ description of homeownership in Seattle, and sources that they cited. If you know of other contemporary sources, or scholarly or otherwise modern sources please share it in comments.

Below I will include relevant sources:

Mintz, Steven, “Sources of Variability in Rates of Black Home Ownership in 1900”, Phylon, 1983. This article describes the very low rate of home ownership by Black people in 1900 compared to white immigrants and US-born white people (9%, 1/3, and 1/4, respectively). It also highlights the wildly different ownership rates between cities for Black people versus stable city to city for white immigrants and native-born. Mintz points out other significant demographic data, such as half of Black people being below age 20 in 1900 in the United States. Detailed statistics are provided for a number of cities, but not Seattle.

Further reading

- The Black staff of Seattle’s Rainier-Grand Hotel

- Frank and Sadie Smith’s home

- Black residences in Pike/Pine in 1910 and 1920

- Auto Row Apartments

- The wedding of Ed Foster and Clara Miller, almost stopped by racists (on CHS Blog)

Seattle’s Black families’ homes on Twitter

I’ve begun profiling each of the homes in Northwest Negro Progress Number on Twitter. Moving forward, I plan to change at least some of these into articles on this site. Until then, you can get to the first tweet in each thread below.

Hayes home tweet thread:

Cayton home tweet thread:

Frank and Sadie Smith home thread:

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.