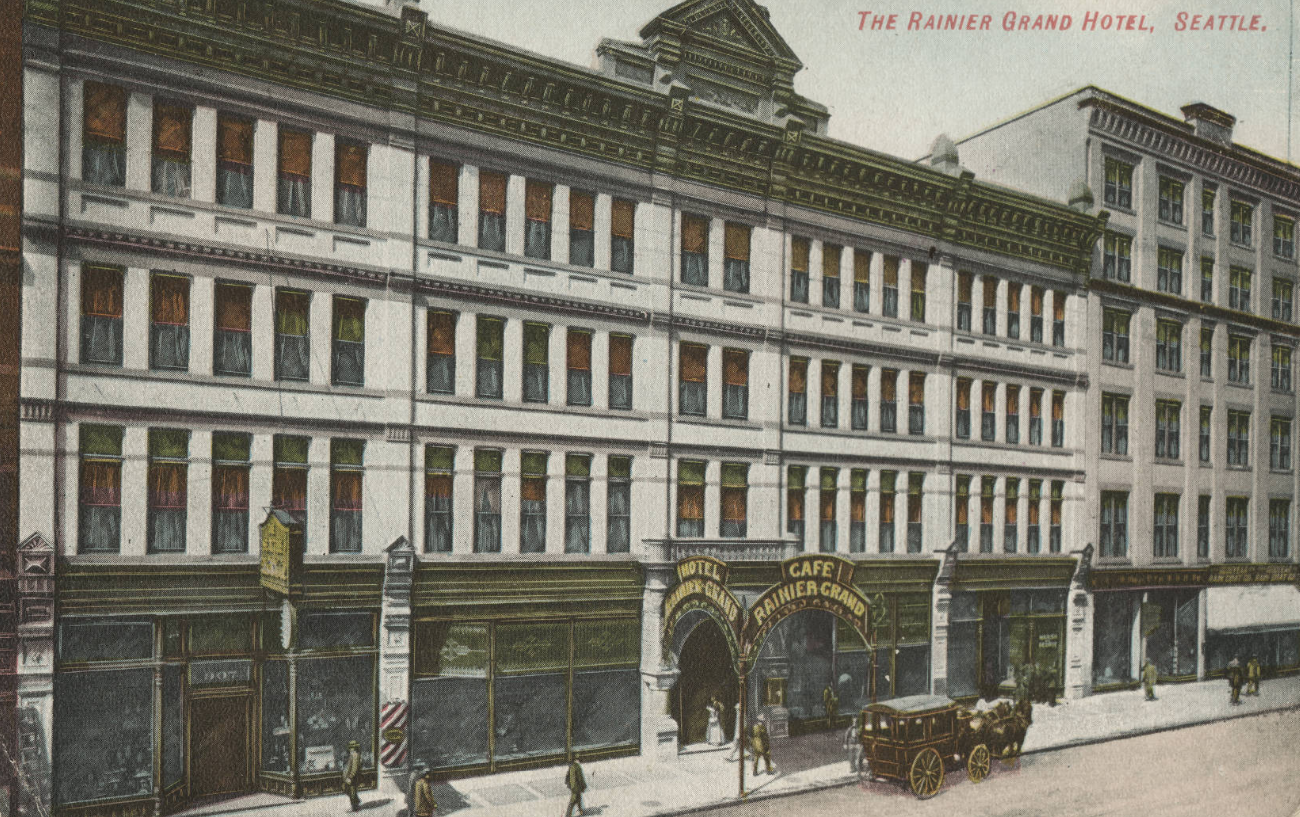

The Rainier-Grand Hotel stood over Seattle’s waterfront for four decades and served as Seattle’s premiere tourist hotel. This is the missing chronicle of the Rainier-Grand Hotel.

Born of fire

The Rainier-Grand Hotel was the descendant of two hotels: the Rainier Hotel and the Grand Hotel. Construction on both of the hotels was underway soon after the Great Seattle Fire in June 1889.

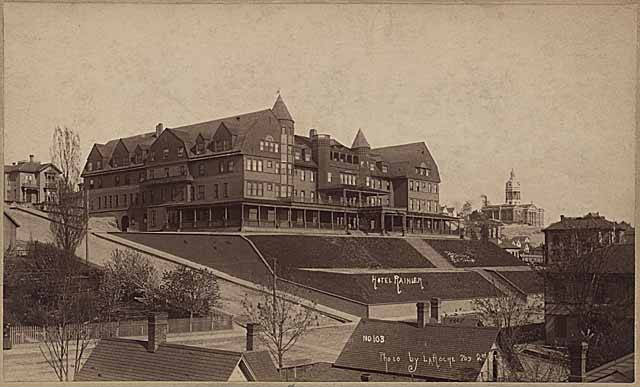

The Rainier Hotel was up on Fifth Avenue between Columbia and Marion streets. L. S. J. Hunt, involved in many city ventures, headed ownership of the hotel. It sat like a wooden castle atop the mid-hill rise at 5th and Marion, and had a commanding view of Elliott Bay from its back steps.

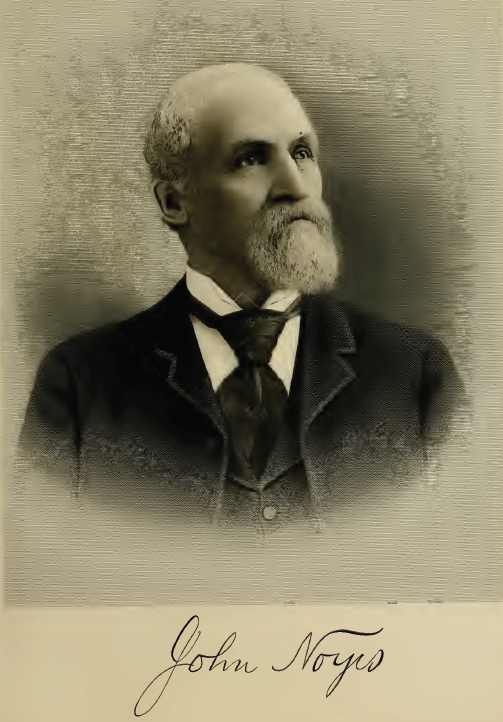

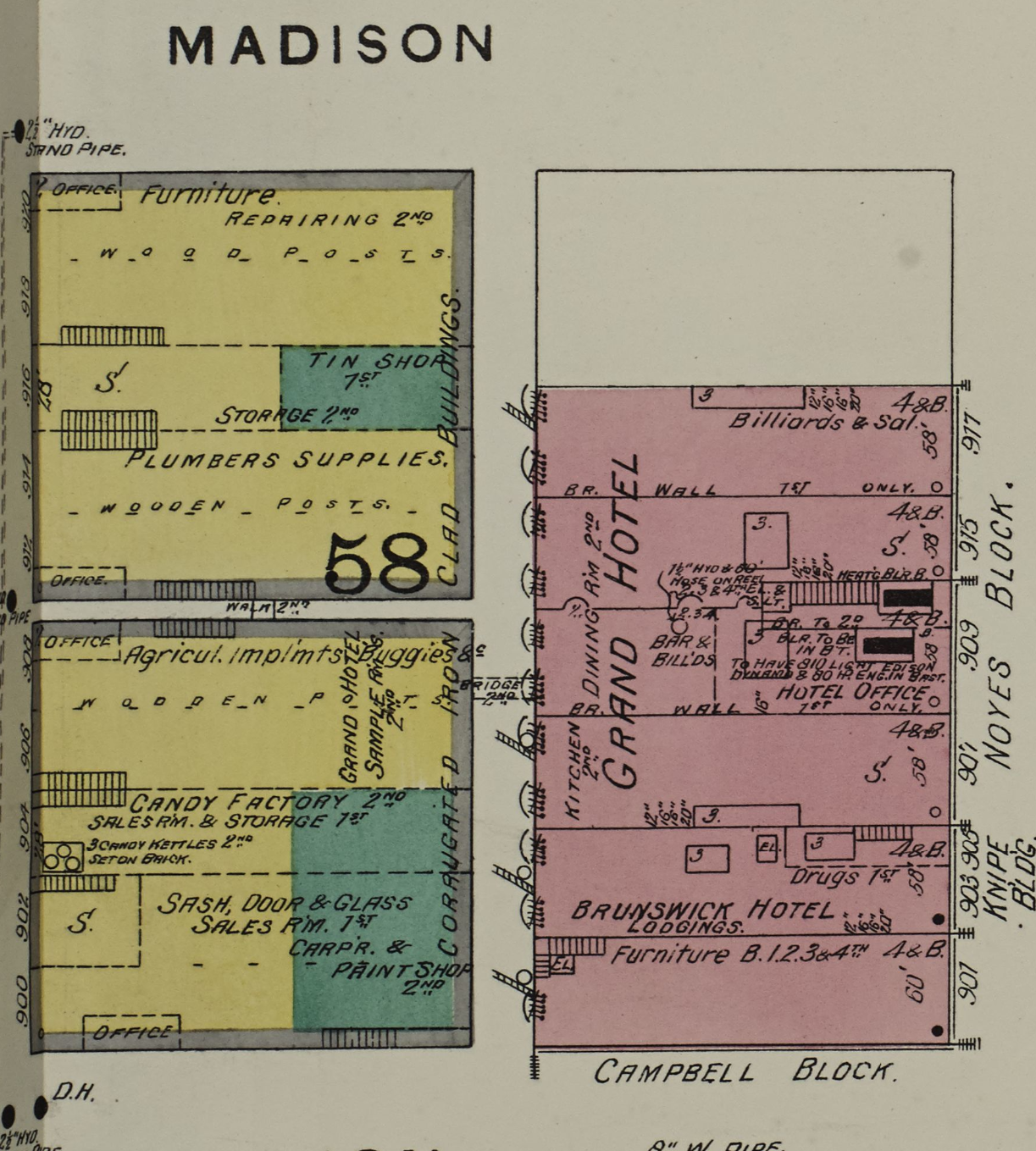

The Grand Hotel was in the Noyes Building down on First Avenue, mid-block between Madison and Marion streets. Initially the design of the Noyes Building was for three floors of offices. However, the opportunity to lease the entire building convinced owner John Noyes to convert it to a hotel.

Both the Rainier and Grand hotels were tourist hotels. They catered to people visiting Seattle for a few days or a month. Many businesses labeled “hotels” at the time were residential hotels, essentially furnished apartments with service. Before they fell to their demise, one of these hotels would transition to apartments.

Noyes

John Noyes, owner of the building with the Grand Hotel, was a remote owner. He lived in Butte, Montana, where he was a prominent citizen.

Starting as a young man with the 1849 California gold rush, Noyes prospected his way from state to state and even up to Canada looking for riches. He finally found true success with two mining claims in Butte in 1866 and bought significant property there.

When Butte took off with rail connections in 1881, copper mining in 1882, and finally a Northern Pacific Railway spur in 1889, Noyes’ land made him very rich. Noyes owned mines and other ventures like Wharton & Noyes grocers.

Noyes invested outside of Butte as well. That led him to buy a building in Seattle next to the waterfront and its slowly expanding rail facilities.

Ante-fire building

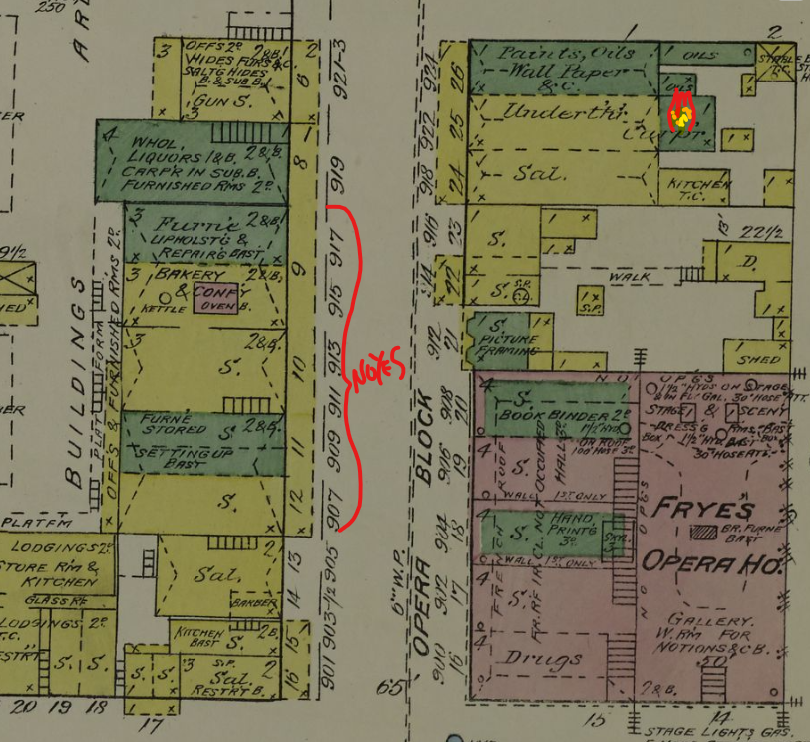

Prior to the fire, Noyes’ property had a two story building with basement opposite of Frye’s Opera House. It was mid-block between Madison and Marion streets on what we call First Avenue. First Avenue’s first name was Front Street because it fronted the water. Elliott Bay came right up to it until just a few years earlier. Behind Noyes’ building the ground fell away under piers for steamers and ships and suspended rail lines.

The 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows his building had rooms for rent and offices on the second floor, and shows the addresses for the storefronts. City directories for 1888 list the stores as a tailor, a general mercantile, a furniture store, a feed store, and a bakery. All of the stores had basements accessible from the rear, used as residences or storage.

An 1889 Seattle P-I article described the entire west side of the street, including Noyes’ building, as “Where the Denny row of wooden flats stood”. Implicitly Noyes wasn’t the original owner. That may have been Arthur Denny, who filed the claim for this land and platted it out. The building already existed in the 1884 Sanborn map of Seattle.

Noyes’ building and 40 acres to the south burned to the ground on June 6, 1889.

The fire started in the building across the street from Noyes’, at the carpentry shop of Victor Clairmont. One carpenter accidentally caught a pot of glue on fire, and another ignorantly tried to put it out with a bucket of water. The fire spread building to building through the basements, and under wooden sidewalks. It burned out the wooden water mains, eliminating any hope of putting it out.

Noyes Building construction

John Noyes’ new building, referred to as the Noyes Building or Noyes Block in papers, gave him more of everything. His burnt building had first floor commercial, separate basement space for each storefront, and a second floor with rooms rentable as offices or residential.

Seattle newspapers gave periodic updates on post-fire construction, including the Noyes Building.

October 1889: “The Noyes block, on Front, between Marion and Madison, will be six stories in height, will be up in sixty days, if weather permits. Brickwork on the first story commenced Monday, and the story with partitions will be up by the last of the week. The work is being rushed as fast as thirty or forty workmen can do it. The Noyes block covers 120×111 feet.”

Early November 1889: “The Noyes building, on Front, between Marion and Madison, has room for 8 merchants and 157 offices.” In the section “soon to be in use”.

Late November 1889: “The tug Phantom left last evening for Dog Fish point to tow up a scow of stone for the Noyes building.”

December 1889: “Where the Denny row of wooden flats stood, on the west side of Front street, in now the partially completed four-story Noyes building and the Knipe and Campbell & Atkinson buildings, both four story brick and iron structures. ”

January 1890: “John Noyes, business block, b[ric]k, stone and iron, four stories, 111×120 feet, Front, near Marion, incomplete; expended to date, $60,000; to cost… $150,000”

In April 1890, John Noyes stayed at the Rainier Hotel when he visited Seattle. But in July, he spent a month in the new Grand Hotel in his own building.

Noyes and Grand Hotel opening

The architect of the Grand Hotel, of the Noyes Building, is forgotten.

But we know who it wasn’t. It wasn’t Byron A. Pugin. Pugin came to Seattle from North Carolina just before the fire, and was ready to do work. He tried to win the job from John Noyes for his building, submitting a draft plan. Pugin claimed he received verbal approval, so he went to work creating complete plans. Noyes rejected them, and in 1890 Pugin sued Noyes for payment for drawing the losing design for the project.

Pugin lost the work, and he lost the court case. Summaries of appeals mention that of course there was another architect who won the work, but unfortunately not that architect’s actual name.

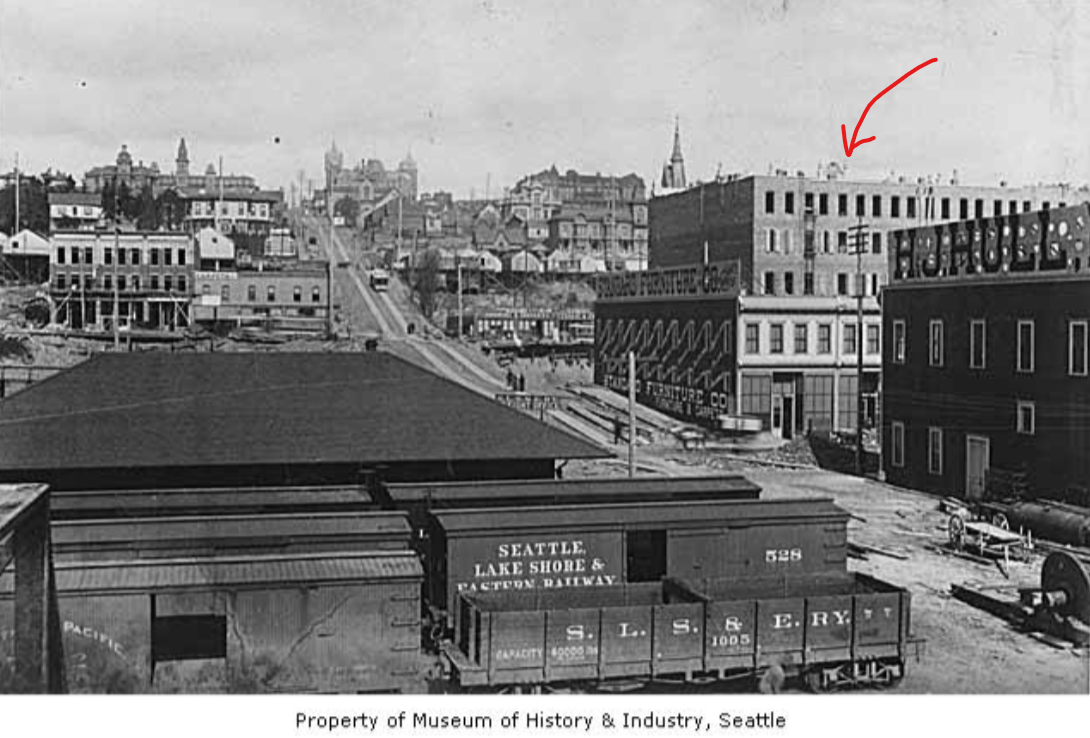

Photographs of the Noyes Building or Grand Hotel from the early 1890s are tough to come by. The back, west side along Post Street is visible in the below photograph from 1891 or 1892. This was looking east from Railroad Avenue (today Alaskan Way) up Madison Street.

The new building was much larger. It included a large basement space, used in early years by a vendor that sold off remaining stock of closed or bankrupt businesses.

The first floor included a range of tenants over the years. In 1890 that included Seattle Crockery, realtor J. Compton & Co’s endeavor The Fair, and D. E. Mulligan’s cigar store.

Soon after Noyes Building construction completed, E. Myer & Company leased the entire upper three floors, initially planned as offices. They opened it as the Grand Hotel. It was a pretentious name, but it accurately portrayed the hotel among the best of Seattle’s tourist hotels.

In 1892 the hotel lease changed hands to Thomas Guinean of Portland, who owned hotels in Portland and Sacramento among other cities.

Rainier-Grand: Life from death

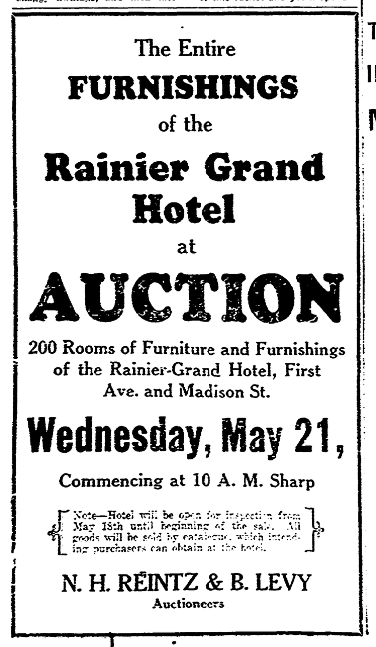

In February 1894 the Grand Hotel closed. The owner, Thomas Guinean, declared his intentions to leave Seattle. He leased the Imperial Hotel in Portland and moved there in February. Guinean had kind words for Seattle and the opportunity for hoteliers, but explained his desire to return to Portland. After a sale of the furniture, the Grand Hotel was empty for most of the year.

John Noyes needed a new tenant. In July he made his annual Seattle visit from Butte. For the first time in years, Noyes was unable to stay in the hotel in his own building, instead lodging at the Northern Hotel. The empty hotel drew unwanted attention. In August newspapers reported that a crooked electrician stole all of the light bulbs and switches from the empty Grand Hotel. Finally on August 16 the rumor first broke that Noyes had found his new business partner.

While the Grand Hotel sat empty, the Rainier Hotel up on 5th was in a failing building. It was simply built too fast. It truly went up in just 60 days, while the Grand construction stretched over half a year. The Rainier suffered from issues like wind coming in around windows and through other cracks. It needed repairs but in the middle of a financial downturn the building owners couldn’t afford to invest.

DeLorme Harbaugh, owner of the Rainier Hotel, decided to move to Noyes’ empty Grand Hotel space down on Front Street instead. Harbaugh said of the Rainier Hotel, “It seems too bad to leave the house, as it has a world-wide reputation of having as fine a view from the porch as any hotel on earth. One reason why I am leaving is that extensive repairs are needed, and the times are too quiet to warrant the proprietors of the property in making them.” Harbaugh included the distance of the Rainier from the waterfront as another major detractor.

After minor improvements finished on the Grand Hotel entry and dining area, and after the light bulbs replaced, Harbaugh closed the Rainier in about September 1894. He moved furnishings from the Rainier down to the Grand and began renting rooms at the Rainier-Grand Hotel in November 1894. The final stage was opening the billiard and grill in February 1895, completing the transition to the Rainier-Grand Hotel.

The “old Rainier Hotel”, as it came to be known, continued as a residential hotel until 1910. Per the October 12, 1910 Seattle P-I, the Fifth Avenue regrade was the reason for its demolition. “Wreckers are tearing the building down just as rapidly as possible,” they wrote.

Two years later the P-I interviewed renowned meat packer J. Ogden Armour during his visit to Seattle. He reminisced that he stayed in the Hotel Rainier on his previous visit, and congratulated Seattle. “I had no idea that Seattle had made such wonderful progress.” Like removing Denny Hill, the willingness to remove the formerly first-rate Rainier Hotel was seen as a step in the right direction.

Black staff of the Rainier Hotel

When DeLorme Harbaugh moved his hotel down to the Noyes building, he presumably took all of his staff.

That included 40 Black men and women who he brought from Chicago in 1889 to help open the Rainier Hotel. They worked as “waiters, chambermaids, laundry women, cooks bellboys, and elevator operators.” per Prof. Quintard Taylor in Forging of a Black Community.

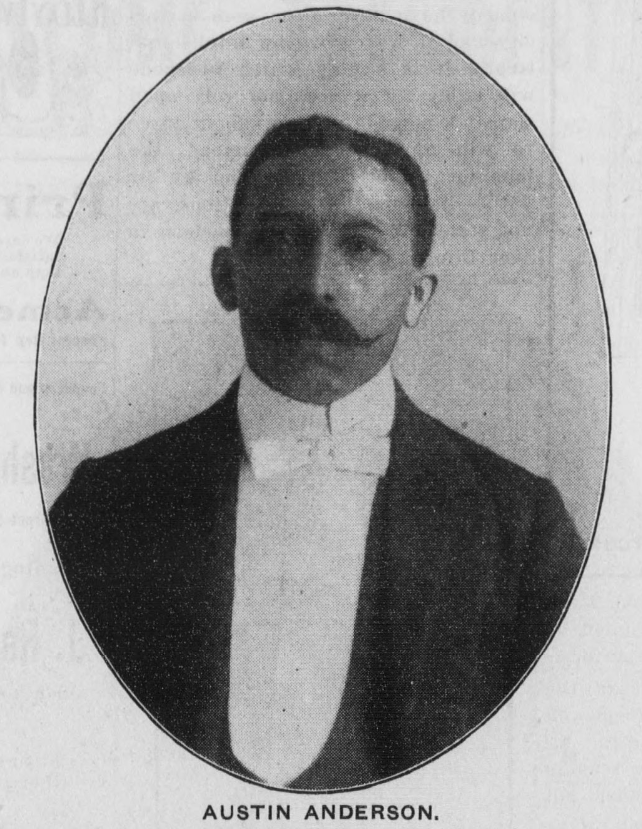

One Black waiter was Austin Anderson, though it’s unclear if he came from Chicago. He later worked as head waiter of the Rainier Club and then the Knickerbocker Hotel (1903).

Another known employee was waiter Lincoln Low (Seattle P-I 9/2/1890), who came to Seattle apparently from Los Angeles and joined the Rainier in about January 1890.

First expansion of Rainier-Grand Hotel

It’s important to remember worldwide economic context for the changes that led to the Rainier-Grand. In 1893 a financial panic gripped America, negatively impacting businesses and limiting investments. This malaise continued to depress the Seattle economy until the discovery of tremendous gold deposits in Yukon Territory, Canada in 1896.

The gold rush that ensued in 1897 then directly boosted Seattle’s fortunes as the launch point for prospectors purchasing supplies. It was also a common return point when they brought back their haul, including the starting point of the rush: the July 1897 return of the steamer Portland with a ton of gold.

The Rainier-Grand Hotel held a perfect location, just a half block from the waterfront. And as prospectors came back rich and unsure what to do with their money, hotel signs beckoned them even before they landed. It was the first high-class tourist hotel they would lay eyes on.

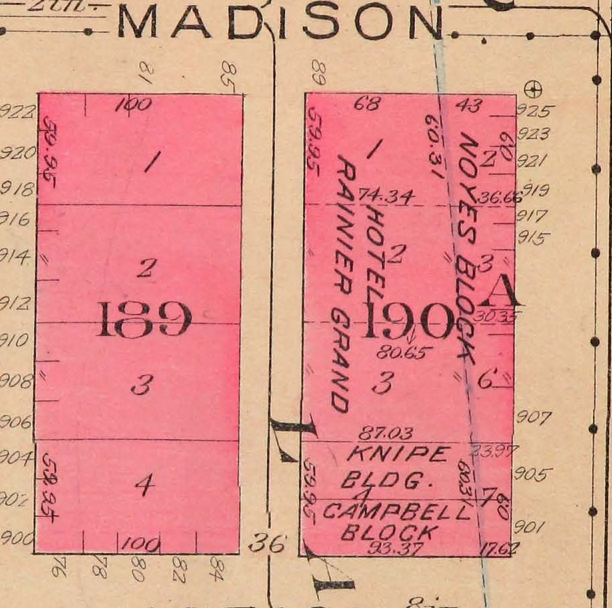

In that improved economic climate, John Noyes purchased the neighboring lot to the north of the hotel at the corner of First and Madison from Albert Pontius in 1897. The Pontius site had high fences used to post “flamboyant theatrical announcements” but was otherwise vacant for the previous eight years, since the Great Seattle Fire.

Noyes hired architect Albert Wickersham to design the new building. (A profile of Albert Wickersham appears on this site.) Wickersham drew plans for six floors in the new building, along with two additional floors on the old.

When Noyes got the construction permit in February 1898 the project was a bit smaller in scale. The old building received no height lift. Focused on the corner lot, Wickersham delivered a seven story corner building at First and Madison: six above First Avenue with a basement facing Post Street. Although papers once more called this new building the “Noyes building”, an annex or addition describes it better.

DeLorme Harbaugh did not continue the lease of the hotel when the annex opened.

Instead, partners Captain Rathbone and Clinton A. Harrison took over at the start of 1899, with Harrison managing. In February Rathbone incorporated the Rainier Grand Hotel Company to own the lease, and took over management. Then they reversed course yet again later in the year, with Harrison taking over management again in May.

Rathbone and Harrison left the scene completely at the end of the year. In January 1900, Horace (H. B.) Dunbar purchased the Rainier Grand Hotel Company. Previously Dunbar for many years ran hotels in Boston and Cincinnati before travelling to the Pacific Coast to find a new venture.

For his part, DeLorme Harbaugh ran the Nautilus Café for some time. When James Moore completed the Denny Hotel as the Washington Hotel in 1903, Harbaugh became its first manager. (More about the Denny Hotel in an article on this site.)

Scandalous gambling at the Rainier-Grand

In early 1903 a grand jury began investigating gambling at the Rainier-Grand Hotel. This led to a case against manager Horace B. Dunbar and indictments of running a rigged gambling room. The case sprawled into an investigation of corruption of the mayor, the city council, and the police department.

The grand jury summary reported on April 1st was no laughing matter.

“In one of the most prominent hotels of the city we found that a game had been running, with paraphernalia for winning money for at least two years, and the proprietors of these games we have indicted. We are satisfied that with an efficient police force such a state of affairs could not exist where men might be fleeced out of sums aggregating thousands of dollars, and this robbery go on unchecked indefinitely…

“This grand jury believes that the chief of police, his captains and detectives, and the patrolmen who had the beat in front of this hotel, were all well aware of the existence of these gambling games. Not only was the faro layout crooked, but the roulette wheel was so controlled, electrically, that a player had absolutely no chance to win. Even the money-paying slot machine in the barroom was so fixed that it was impossible for any one but a booster to win money playing it, and the cigar machine in the lobby of he hotel was doctored in such an extent that a player who won a cigar was looked upon with suspicion.

“The jury has the names of two players against the Rainier-Grand hotel games; one of whom lost $11,800, and another $23,000…

“The mayor and council, acting in conjunction with the chief of police, might have given us a morally healthy city, but the mayor seems to have misinterpreted the desires of the people in that he thought a wide-open policy, which he had promised them before the election, meant unrestrained vice.”

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Apirl 1, 1903.

Forces in Seattle were once again trying to eliminate the vice and corruption that plagued the city for so many decades.

A grand jury convened and indictments began dropping just past New Year’s Day 1903. Rainier-Grand manager Dunbar was indicted along with two card dealers on the first day. They were William Harry (W. H.) Fazon and Mark Hoff (or Huff), who ran the gambling room. Fazon fled from Seattle to Vancouver, B. C. Months later Colorado police arrested him on unrelated charges, but the governor refused to extradite him. Hoff was missing for weeks and eventually spotted in Victoria, B.C. Neither Hoff nor Fazon ever faced the grand jury.

In an interview with the Seattle P-I, Dunbar admitted that there was gambling happening at the hotel, like everywhere else, because the city was “wide open”. Dunbar opened a social club in the hotel just for that purpose. He objected, however, to the idea of illegal modifications to the gambling devices. Dunbar claimed that if they happened, he had no idea.

Among the dozen civic leaders that rose to Dunbar’s defense and funded his bail were Donald Frederick and Nels Nelson, the founders of Frederick & Nelson department store.

Various employees of the Rainier-Grand Hotel were brought before the grand jury as witnesses, including clerks and waiters.

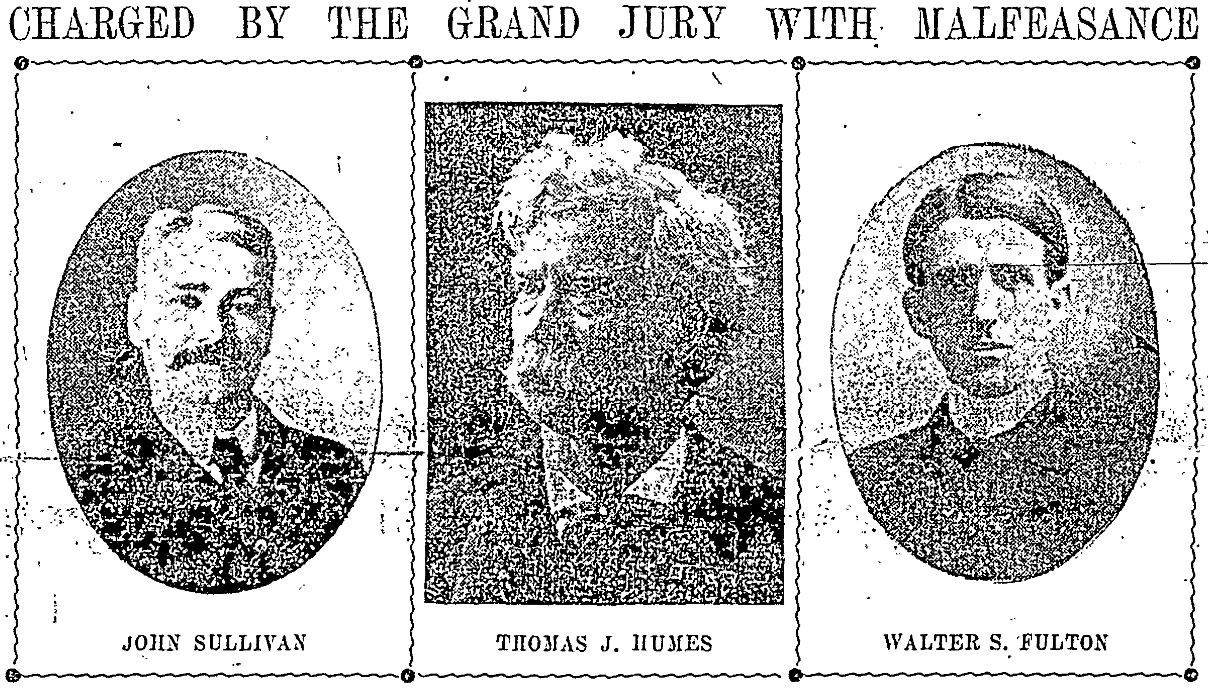

In March the indictments spread to Mayor Thomas Humes, Chief of Police John Sullivan, and former King County Attorney Walter Fulton. They were all accused of malfeasance in office and neglecting to enforce the ordinances of the city.

Get out of jail free

Almost two years after the case began, Dunbar was free and clear. The county’s victim in the case, Hermann Beckman, refused to return to Seattle to testify. He told the grand jury in June 1903 that he lost $3000 in a rigged game. But in December 1904 he wrote from Ohio saying that he would not testify at trial. The King County Attorney dismissed the cases against Dunbar, Hoff, and Fazon.

City officials were let off the hook much sooner. In April 1903, just a month after his indictment, Mayor Humes filed a demurrer against his indictment. In a demurrer, the defendant essentially says “If I did do it, I’m not guilty of anything.” Mayor Humes’ argument was that the city mayor has no obligation to prosecute people that they know have violated the law: that is the responsibility of police and the prosecuting attorney. Judge Bell agreed, and Humes was clear of his indictment.

Chief of Police John Sullivan escaped on a thinner tight rope. His trial was set for June but delayed to September after the death of his lawyer, John F. Dore. Just before it was set to commence, King County Prosecuting Attorney William T. Scott decided to drop charges. There was no real explanation for Scott’s action. His argument was that since Humes couldn’t be held accountable for failing to arrest criminals, neither could the Chief of Police.

A few weeks later, former King County Prosecuting Attorney Walter Fulton found absolution as well. In his case the prosecutor determined that because Fulton was a prosecutor, it was wrong to expect him to make arrests and find evidence against criminals. Since the Chief of Police didn’t bring him the cases, he was not guilty of malfeasance and failing to due his duties.

Along the way, Rainier-Grand Hotel waiter Frank Smith got caught up in the ordeal. He was accused of perjury by the grand jury, who couldn’t believe he knew nothing about gambling at the hotel and had never himself gambled in his entire life. Like his boss Horace Dunbar, Smith’s case was dismissed in December 1904. (A profile of Frank Smith appeared on this site.)

Noyes family takes control

John Noyes fell ill and died of pneumonia in March 1902 at age 73.

Ownership of the Noyes building passed to his estate, owned fractionally by his wife Elmira Mieklejohn Noyes and four children Alice, John, Thomas, and Ruth. Alice’s husband Wallace McClintock White and Ruth’s husband Arthur Heinze (brother of Augustus) also got involved in managing the Noyes Estate.

The gambling charges against Dunbar were too much for the Noyes family.

Even before his lease expired at the end of 1903, the family filed suit against him, hoping to remove him from the hotel. In early December they claimed $75,000 damages because of the hotel’s poor condition and reputation.

The Seattle P-I said, “It is specifically alleged that at divers times the defendant has used the premises for gambling purposes” and described an assortment of failed repairs and violations of contract.

Dunbar attempted to sue to stop the lease transfer but lost. The Noyes estate secured a writ in federal court, and on January 12, 1904, U.S. Marshals Tyler and Crosby forcefully evicted him from the hotel. Dunbar refused to leave, but moved himself in front of the open door so that Crosby could push him out with a “gentle shove”.

Dunbar moved to New Orleans where he took over the Hotel Denshaud. In a 1922 remembrance, the magazine Hotel World wrote, “He came near being a big man, but was a little short on ethics.”

The contract to manage the hotel stayed in the family. It was leased to a new firm, Wilson & White Company. “White” was Alice Noyes White’s husband, Wallace. “Wilson” was Hugh Wilson, who owned and ran the high-end Butte Hotel in Butte with his brother Frank. A third partner, Charles Perry, stayed at the hotel and ran day-to-day management.

In 1909 Alice Noyes White remarried Dr. Thomas J. Murray, a friend of the family. Wallace White remarried in 1912. Wilson & White continued to lease the hotel from the Noyes estate through 1916, so the divorce must not have been too messy.

Rainier-Grand’s Black staff

The way the Noyes family forced Dunbar out illustrated their dissatisfaction with the state of the hotel. It’s understandable that they would make staffing changes after the gambling trial tarnished the hotel’s image.

However, the change that did take place was disturbing. Despite initially announcing that Wilson & White would retain all of the Rainier-Grand employees, they quickly fired all of the Black staff.

Hugh and Frank Wilson’s Butte Hotel had an entirely white crew living on-site. It’s possible that like Dunbar they wanted to bring in staff that they knew and trusted. Another possibility, though, is that they chose not to employ Black people. Other hotels near Butte like the Montana Hotel in Anaconda, Montana or the Knutsford Hotel in Salt Lake City, Utah had Black employees. When the Wilsons visited one of those hotels they could see how it differed from theirs.

We know the stories of some of Rainier-Grand’s Black employees due to profiles in the Seattle Republican, along with other documents.

An extended biography of Frank Smith is appears on this site. His life after the Rainier-Grand is much better known than his life beforehand. He was born in Knoxville, and grew up in Indiana before coming to Seattle in his mid-20s.

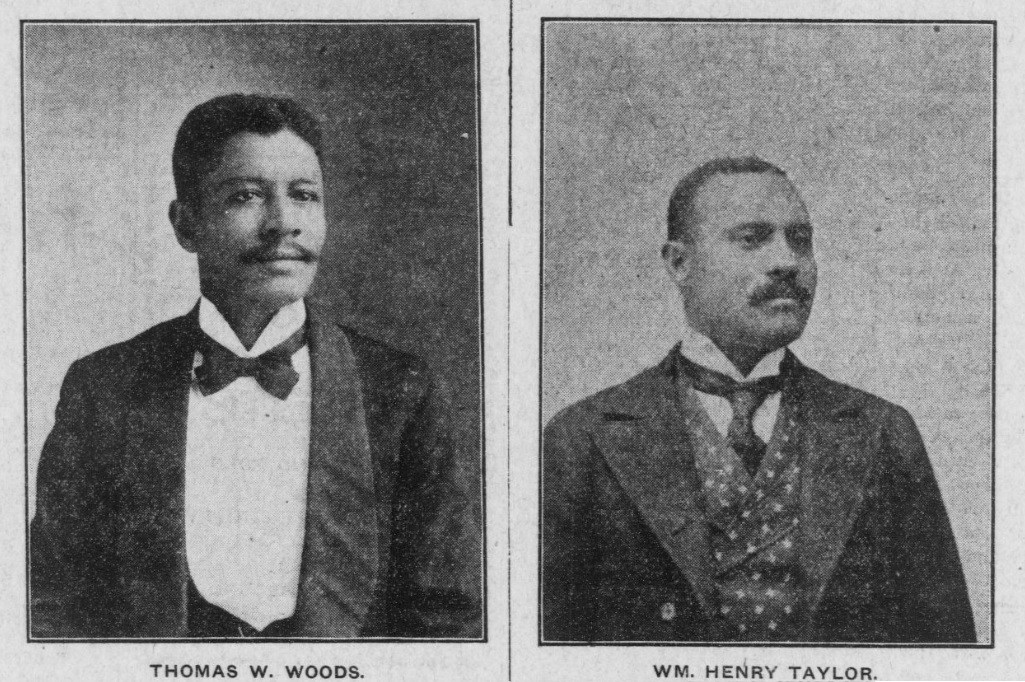

Two other Black men that worked at the Rainier-Grand were profiled by the Seattle Republican: William Henry Taylor and Thomas W. Woods. The text accompanied photographs (below) on the front page of the March 7, 1902 issue.

William Henry Taylor no longer worked for the Rainier-Grand by that time. Taylor was born in Princeton, Kentucky. After working in Los Angeles as second waiter at a hotel for a dozen years, he moved to Seattle in 1900. He worked at the Rainier-Grand Hotel for a short time as the “captain of the watch”. Within a year he moved on, joining the Rainier Club and returning to his position as second waiter.

Rainier-Grand head waiter Thomas W. Woods

Thomas W. Woods held a prominent role at the Rainier-Grand Hotel when his profile was published in the Seattle Republican on the March 7, 1902.

“Thomas W. Woods. Head waiter of the Rainier-Grand Café and professional caterer, was born in Birmingham, Alabama. When only eighteen years of age Mr. Woods was made head waiter of the Florence Hotel of that city, which position he held for nine successive years. Having a desire to come West, he pulled up in San Francisco in 1892, where for two years he had charge of the dining room of the California Hotel. The Alaska gold excitement tuned his attention toward the Northwest, and in company with a regular crew he came to Seattle in 1899, when he was employed as a waiter at the Rainier-Grand Hotel.

His ability to successfully manage a dining room soon asserted itself over his fellow waiters, and the proprietor was not long in discovering that Woods was the one for his dining room, and he was promoted to the head waitership of the Rainier-Grand, which position he has successfully held every since. His in-born Southern politeness is very cleverly handled by him and he never fails to capture the hearts of his guests wherever he is employed. With such head waiters as Mr. Woods the disposition on the part of the proprietors of large hotels to supplant the colored waiter with white waters will die ‘a-bornin.’ Mr. Woods is assisted in his work by an excellence crew and Mine Host Dunbar should feel himself exceedingly lucky in getting them.”

Seattle Republican, March 7, 1902

Thomas Woods left the Rainier-Grand in mid-1903 to move to the Hotel Washington (previously left unfinished as the Denny Hotel), where former Rainier-Grand manager Delorme Harbaugh became the hotel’s first manager.

The Seattle Republican again graced Woods with a profile after his move. They said of him “Who is both polished and polite, and, best of all, a captain of his profession, has been able to force those having his kind of business to be done to recognize him for his true worth… It was the masterly manner that Mr. Woods handled his subordinates in serving monster banquets from time to time in Seattle that prompted the proprietors of the ‘Washington,’ the largest hotel north of San Francisco, to offer him extra inducement to take charge of the dining room of that hostlery… He almost starts the new hotel off by serving President Theodore Roosevelt and his party, the most distinguished guest he has or ever will again serve.”

In 1904 the Seattle P-I profiled Thomas Woods as well with an autobiographical sketch. It incorrectly said that he was the first Black man to be a head waiter in Seattle. Woods described his background. He was born on July 4, 1869, and came to Seattle in about 1895. “I came to Seattle to take charge of the Rainier-Grand hotel [dining room], bringing with me a crew of men from [the Baldwin Hotel in San Francisco,] California.” He described the he at times employed white waiters, but that they were generally Black men.

After the P-I’s profile, Seattle Republican issued a correction, explaining that James Orr was the first, at the Arlington Hotel from 1882 to 1884. Orr moved to the Occidental Hotel after that. Then Thomas Johnson and a Mr. Wright were head waiters at the Rainier Hotel prior to Thomas Woods taking over at the Rainier-Grand Hotel, perhaps making him the fourth.

Woods ended his sketch in the 1904 P-I saying, “I hope the waiters in Seattle will hold the foundation I struggled so hard to build and give creditable service to the employer as well as to themselves.”

Edward Page and other Black men at the Rainier-Grand

In early 1902 the Seattle Republican newspaper ran an advertisement for a “Grand Masque Ball and Cake Walk” hosted by the waiters of the Rainier-Grand Hotel. The staff listed by name were Jack Bailey, George Davis, Al Duncan, W. Fields, Frank Smith, Richard Smith, Fred Burton, Ed Page, Richard Stevens, and Newton Williams. Frank Smith and Ed Page were definitely Black men, and it’s likely that all of these men were.

In 1902, Edward Page was the head bellman, valet, or messenger of the hotel. He worked for Horace Dunbar for 20 years per the Seattle P-I and came with him from Dunbar’s hotel in Cincinnati. The Seattle Republican said about his 1902 funeral that “the entire [Dunbar] family attended as well as all the clerks, and during the services it was plain to be seen that Mr. and Mrs. Dunbar were visibly affected.” Page meant more to them than an employee, and he and Horace “were nearly inseparable.”

Page died of kidney disease in 1902, two years before the Noyes family forced out Dunbar and fired the rest of the Black staff. The death registry inconsistently lists his age as 49 and his year of birth as 1859. Either way, he was born a slave in Kentucky.

At least four of the pall bearers at Page’s funeral worked at the Rainier-Grand: Thomas Woods, Newton Williams, W. W. Wheeler, and Frank Smith. Again, Woods and Smith were definitely Black men and it’s likely that the entire list were.

Many of the staff lived at the hotel. The “servants” listed in the 1900 census at the Rainier Grand Hotel included Ellen Mattson, G. H. E. Thompson, E. E. Caine, H. W. Johnson, R. Stokes, H. Dean, W. W. Wheeler, J. M. Bailey, H. Duncanson, H. Harris, G. Gordan, F. Wells, H Gaston, a Mr. Ryan, W. Austin, Robert Champ, and Thomas Woods.

All of these 1900 staff were listed as “white” in the census, but for example as described here Thomas Woods was definitely a Black man. Several other of these men were also Page’s pall bearers or in the masquerade event, so presumably most or all of them were actually Black people.

Another Rainier-Grand Hotel expansion?

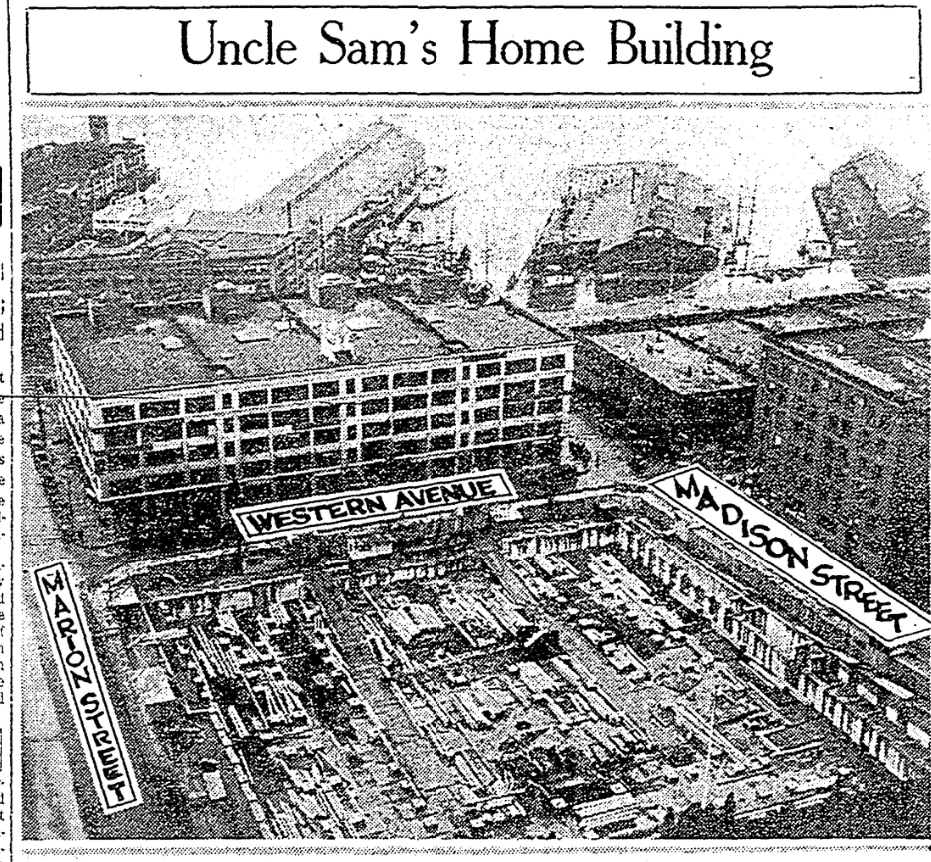

In 1909 Seattle hosted its first World’s Fair, the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition. Yet another boom for Seattle meant yet another boom for the hotel industry. The Rainier-Grand intended to join the hustle, but instead the Noyes family built a warehouse.

In 1908 the Noyes estate hired architect W. A. O’Brien to design a proposed annex on the west half of the block. This time papers called it the “Rainier-Grand Hotel Annex”.

The annex would fill from Madison to Marion, between Western Avenue and Post Street. It would be as tall as the existing hotel, which meant extra floors from Western Avenue’s lower elevation. Bridges would link the two hotels at each floor above Post Street.

However, construction faltered before it began, for an as-yet unknown reason. Perhaps it was due to the financial downturn at the time. Ironically, the Panic of 1907, began when Ruth Noyes Heinze’s brother-in-laws Otto and Augustus failed to corner the market on United Copper stock.

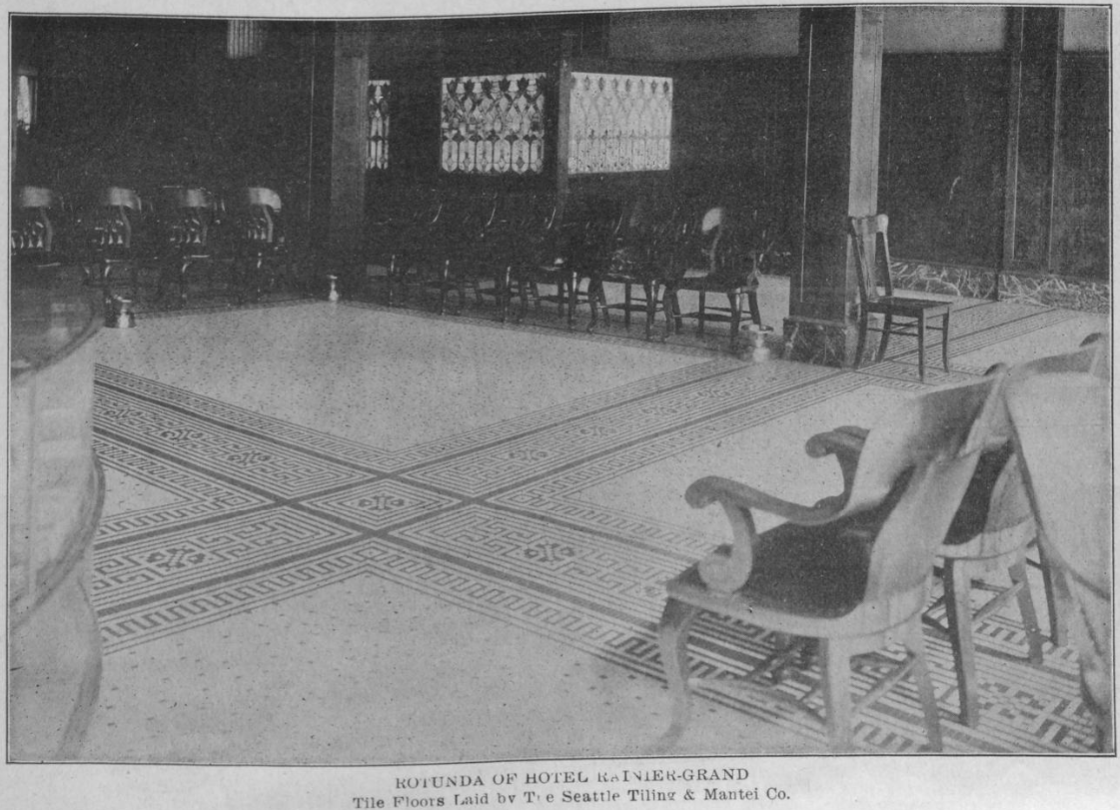

Just before the panic, the Noyes family completed a remodel of the Rainier-Grand Hotel rotunda with ceramic tile. Work was done by Seattle Tiling & Mantel Company. This earned them recognition in Pacific Builder & Engineer and the trade magazine Brick.

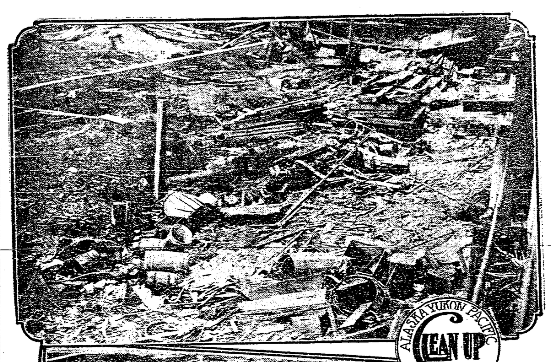

In April 1909 the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition committee celebrated a small accomplishment: the cleanup of the construction site. They pushed everyone to make the city tidy before thousands of visitors arrived. Left mid-work, debris covered the site, left over from either demolition or the delayed digging of the foundation for the new hotel.

Construction finally commenced after the close of the close of the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in 1909. An Asahel Curtis photo held the UW Special Collections shows progress underway in October.

Instead of a hotel annex, though, the Noyes family built a brick warehouse on Western Avenue. Several new high-class hotels opened while their project stalled, like the Perry and Sorrento up on First Hill. There was definitely demand for warehouse space on the waterfront. The apparently went after the easy money.

The Claussen Brewing Association quickly rented at least part of the building for offices and cold storage in March 1910.

Rainier-Grand leaves Noyes estate

In January 1916 Wilson & White sold the hotel lease. The hotel stayed in the family, though. The purchaser was Dr. T. J. Murray, the vice president of the Noyes estate and second husband of John and Elmira Noyes’ daughter Ruth.

Charles Perry left the hotel with the end of his company’s lease, heading out on two months vacation before finding a new position.

Two years later, the hotel lease changed hands again, leaving the Noyes family for the first time since they forced Dunbar out in 1903. Seattle businessman and art collector James J. Kelley took over the lease.

Kelley previously owned a saloon and alcohol delivery service. Both businesses became illegal in 1915 in Washington State. Years later the Seattle P-I shared his early biography:

“James J. Kelley, the present owner [of the Rainier-Grand], migrated to the West in the early days, became a cowboy and later was manager of the C-12 ranch in Wyoming and Nebraska with a range of seventy miles long and from fifteen to thirty miles wide. At one time this imperial holding, Kelley said yesterday, grazed 65,000 cattle.”

Seattle P-I, 1/15/1929

Kelley managed the hotel directly and installed his art collection on the walls. There’s no mention today of the artists mentioned in Kelley’s ads and promotional articles, but thankfully one old description remains from that same Seattle P-I article. “One of [Robert Swaim’s] quaint conceits is labeled ‘Seattle Spirit’. It represents an infant with a mischievous light in his eyes, smoking a pipe.”

The Kelleys frequently hosted public art events in the hotel to maintain its image. Kelley became a prominent hotelier and president of the Washington Hotel Owners Association.

End of the Rainier-Grand

In the late 1920s the United States government began looking for land for a new federal building in Seattle, to consolidate offices and provide a new post office. In 1929 they settled on the Noyes block, which still included two buildings under separate ownership on the southeast corner.

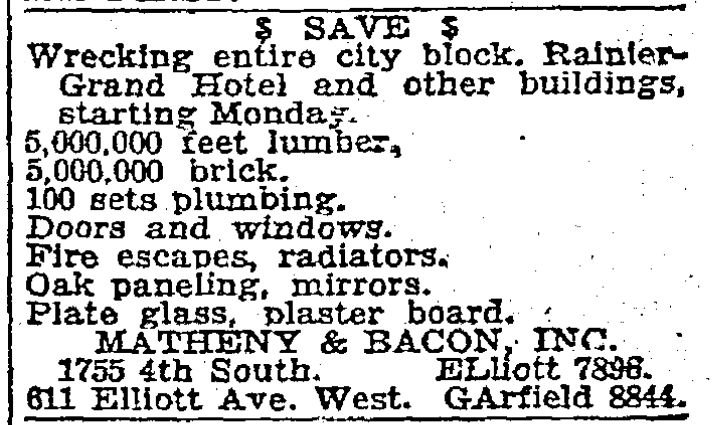

Demolition of the Rainier-Grand Hotel began June 1, 1930. Then, construction began for the federal building in January 1931 with soil samples, pile drivers, and foundation laying. After three years of work the new building opened in 1933.

Over the years the Rainier-Grand Hotel occassionally appeared in newspapers articles about Seattle history. Everyone remembered how glamorous it was, and what a fine hotel it was. And, like Armour after the Rainier Hotel demolition, Seattleites endlessly congratulated themselves for Seattle’s progress.

Getting rid of fine things simply to get new ones is apparently part of who we are.

The Rainier-Grand is no more. Basic facts like date of construction are wrong in authoritative sites. No history of Seattle spends much ink on it. Oddly, the only commemoration is a century-old false boast of the hotel.

On the Great Seattle Fire’s anniversary in 1952, assistant fire chief Robert B. Rogers held a media event at the Federal Office Building. He was a boy when the fire happened. He was part of a group that hung a plaque remembering the fire in the Rainier-Grand Hotel. The fire department salvaged that plaque in 1930 and kept it safe for two decades. It took six years, but Rogers’ plea to hang it again reached the right ears. The federal government finally worked through the approval process and added the plaque where it remains today.

The plaque claims this location as the starting point of the Great Seattle Fire in 1889. But as described at the start of this article, the fire did not start here. It started on the other side of First Avenue. The real significance of this plaque is that it previously hung at the Rainier-Grand Hotel, claiming a false place in history.

And forever, the Rainier-Grand Hotel will only remain as the genesis of err and confusion for Seattle historians.

Further reading on related topics:

- The story of waiter Frank Smith

- Seattle’s Black Families’ homes in 1909

- Revealing Albert Wickersham

- The Denny Hotel construction lasted one long decade

- Rebuilding Seattle after the Great Fire, all 1890 buildings

- 1895 street renaming

- Hoeslich and his street clock are mentioned in Pike’s Forest of Clocks

Also my book Lost Seattle is very on topic for this article.

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Your article asserts that the Great Fire started on the east side of Front Street, even marking the location on the Sanborn map, and I admit there is some evidence that this was the location of McGough’s paint shop, putting the Clairmont Cabinet shop beneath it. Not the least of evidence is the mention of 922 Front, and the listing for McGough in 1889 at the “s e corner” of Front and Madison.

However, there are just as many, in not more references to 921 and 923 Front Street, and the southwest corner of Front and Madison. And the contemporary accounts, written the day following, speak of the flames first going upward to the ceiling, which was the floor of the residence and boot and shoe shop of P.J. Madigan, 923 Front Street.

Many accounts speak of the businesses taken, in order, next. Each of these businesses, Dietz and Meyer’s liquor store where the barrels exploded, Queen City Bakery, Crystal Palace Saloon and Opera House Saloon, all occupy the west side of Front St between Madison and Marion, not the east.

The accounts the following day all point to the west side as the starting point. I can excuse a typo or an error by directories, showing McGough’s paint shop incorrectly on the southeast corner far more easily than all of the first-hand accounts the following day that clearly state that the fire began on the west side of Front.

I’d love to compare notes.