Seattle still has a bunch of street clocks. (Those clocks on poles in the sidewalk.) Almost a dozen, which is more than just about any city out there. But, Seattle used to be known as the City of Clocks. There were street clocks everywhere, and most of them were made by Seattle’s own Joseph Mayer.

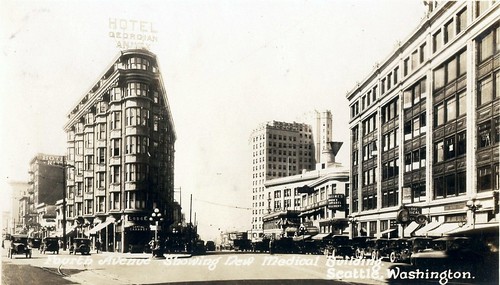

For example, let’s talk about 4th and Pike in 1930. 1930 was peak street clock time in Seattle, after the roar of the 20s, and before the depression of the 30s. At that one intersection, there were as many street clocks as we have street trees today. 16 clocks within a short distance!

On September 29th the Seattle Times ran a short editorial blurb:

“A reader submits the following:

‘A person standing at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Pike Street, Seattle, can see the faces of sixteen street clocks, not one of which is more than one block away.’

He could have added with a fair degree of accuracy that it is seldom that any two of the clocks show the same time.” ST 1930 09 29 p1

Ignore that jab at the end for a minute. 16 clocks is an astounding number. There were twelve within one block really, and going out another block covered a full 16. Even if you remember that Westlake continued all the way to the intersection of 4th and Pike back then to make a five-corners, that is still a tremendous number of clocks within a short distance. Even more were visible down the street from 4th and Pike.

In this article I will show you the 16 in pictures, and give brief accounts of the clocks and jewelers. Ten of them were designed by Joseph Mayer and two more street clocks came from Boston’s E. Howard & Company — at least one was brokered by Mayer.

East: The First Six

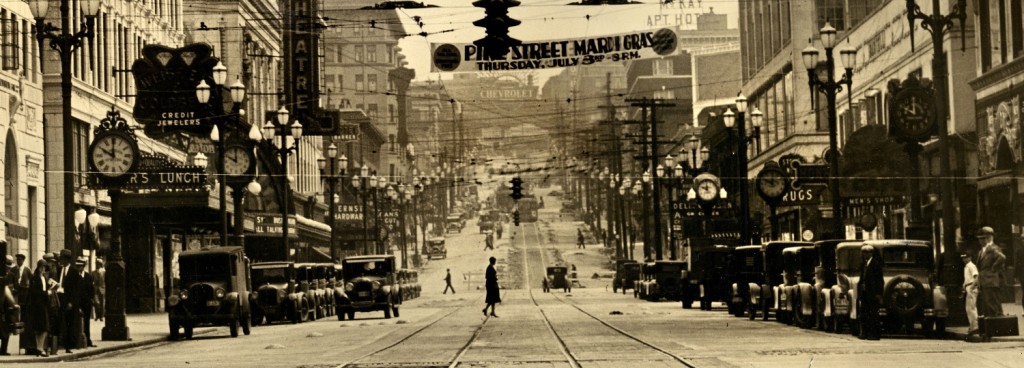

Here’s what the scene looked like three months earlier, in June of that year. In the distance, Pike Street rises and turns just before Bellevue Avenue on its way towards Broadway.

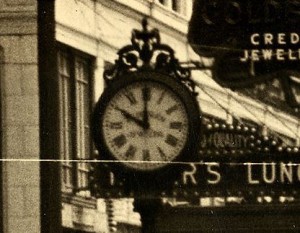

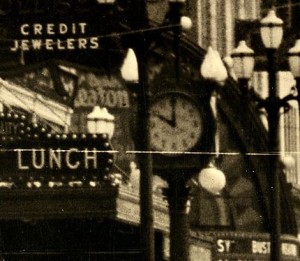

From this vantage we can see six of the 16 clocks. They’re a big variety. From left to right:

1. Jesse S. Hoeslich, 404 Pike

The first clock on our list was owned by Seattle native Jesse S. Hoeslich. Jesse was son of jeweler and Romanian immigrant Joseph Hoeslich and presumably nephew of jeweler Emanuel Hoeslich. The second gen Hoeslich was located here through the end of 1941, and the clock’s fate after that is unknown.

The clock was purchased by Friedlander, Hugh Harrison & Company at 925 First Avenue from E. Howard through Joseph Mayer in 1908. Sam Friedlander moved the clock to 1300 Second with his store in 1915. In early 1917 Friedlander purchased a new four-dial Joseph Mayer (the same style as Ben Bridge’s current clock), and this clock was purchased by Bailey & Brashem back at 921 First. Hoeslich then purchased it from them in 1924. The style is referred to as a fancy top 12 foot two-dial model.

2. Weisfield & Goldberg, 414 Pike

Weisfield & Goldberg started in 1917 as a small watch shop on Third and Union owned by Sam Weisfield. Sam’s cousin Ralph Goldberg joined him in 1917.

Weisfield & Goldberg’s clock was a massive eight-dial clock. It was so big that in addition to the four dials in the clock head, another four were placed at eye level for pedestrians to reference. It was designed and built by Seattle’s Joseph Mayer. Weisfield & Goldberg installed it in 1919 in front of their store at 302 Union. The clock cost $3600 at the time, about $50k today.

The clock moved to 310 Pike in 1924, and then to 414 Pike in 1926. That’s where we see it in 1930. It moved with the store to 420 Pine in 1958.

The fate of the W&G clock after 1967 is unknown. It was at 420 Pine Street at that time. W&G was renamed Weisfield’s in 1948 after Ralph Goldberg’s 1941 death. In 1967 Weisfield’s was the fifth largest chain in the country and still growing. It was recently acquired by the Sterling mega-chain and rebranded.

3. C. G. Sutherland, 520 Pike

Out in the distance on the left, in front of the Ernst Hardware sign, was the clock of Charles G. Sutherland. He came to Seattle from Minnesota in 1899, opening a watch shop on Denny Hill. In about 1909 he moved into an office in the People’s Savings Bank Building at 2nd and Pike. After working for jeweler Peter Michael for one year, Sutherland moved into a street level retail space at 5th and Pike in 1919. He purchased his clock in 1925, a late-model Joseph Mayer two-dial design. In 1932 Sutherland gave up on retail during the Great Depression. He sold his clock to Ryotaro Asakura, who had a successful jewelry shop on Jackson Street. Sutherland died of a heart attack in 1937.

An aside on Ryotaro Asakura. He was born in Japan in 1890, arrived in the US in 1904, and by 1910 lived in Seattle. He worked as a watchmaker and in 1917 opened his own shop on King Street. In 1921 he lost his license after the City of Seattle passed a racist ordinance declaring that non-citizens could not be pawnbrokers. Asakura fought this all the way to the Supreme Court and won. Unfortunately this was not on civil rights grounds but only because a 1911 US treaty with Japan said that citizens could work in each others’ countries. Asakura ran his business successfully through the Depression until his imprisonment with other Japanese in 1942. The fate of the clock at that point is unknown. Asakura and his wife apparently stayed in Idaho after their release from Minidoka, joining a large Japanese American community in the welcoming city of Ontario, Oregon. They are both buried there. His children seem to have returned to Seattle. A son died here in 2009 and a daughter in 2010.

4. S. Friedlander & Son, 501 Pike

Samuel Friedlander first appears in the Seattle city directory in 1909, in partnership with Hugh Harrison in a store at First and Madison. Friedlander’s advertisements later made the confusing statement that the store was established in 1886, but for example a 1966 article clarified that the 1886 store was in Columbus, Ohio. That same article said that Friedlander moved the business in 1904 to Seattle, but so far 1908 is the earliest confirmed date, when Friedlander and Harrison ordered the clock described above (Hoeslich). After Friedlander installed the Mayer four-dial clock at 2nd and University, he then later purchased this huge Mayer eight-dial in 1928 at Fifth and Pike.

The business was sold in 1986 to the Sterling Company, and still exists in some form at least on paper.

The last confirmed sighting of the clock was 1956.

5. W. F. Larne, 419 Pike

I wrote about this recently along with the history of Menashe & Son’s clock in West Seattle.

In 1923 W. F. Larne purchased a clock from Joseph Mayer and had it installed at 4th and Pike. It was mid-block on Pike on the south side. The area was already full of jewelers and clocks, but by 1930 4th and Pike had a ridiculous number of clocks.

The clock moved to the Junction in West Seattle in 1950. It was destroyed by a delivery truck and removed in the early 1980s.

6. Ben Bridge, 405 Pike

Samuel (or Simeon) Silverman immigrated to the United States from Russia in 1905. He brought his wife and three children over in 1906, and they eventually settled in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Samuel owned a jewelry store. They relocated to Seattle, joining his younger brother who was already established.

Silverman’s early years are a bit murky, with some details not well recorded or remembered by the Bridge family. When Ben Bridge retired in 1956, Silverman’s arrival in Seattle and store opening was mentioned as 1913, matching earlier accounts. By a 1972 ad, and continuing today, it was described as 1912. The first city directory listing for Sam Silverman was in 1914. I have not personally seen any direct evidence earlier than 1914.

Also, until the last couple of decades the first store was described as being at First and Madison, which matches the 1914 directory. However in Herb Bridge’s book Building Bridges, repeated from a 2000 interview, he described the first store as located at 1322 Third Avenue and included a photo of Silverman at a storefront that clearly says 1322. It can’t be 1322 Third because that was the location of the Federal Building (Post Office). Other blocks also don’t yield a good candidate. At this point I am suspicious that the photo may have been actually taken in Altoona, and hope to confirm that.

Update 2/10/2022: In an email from Zach Bridge in 2020 he shared that he had tracked down the mysterious “1322” to Silverman’s store in Erie, Illinois, before he came to Seattle.

Back to the narrative…

By 1914 Samuel Silverman opened a jewelry store at 1010 First Avenue working with his wife and son. A year later he was listed in partnership with Joseph Freeman. Ben Bridge married Samuel’s daughter Sarah in 1922 and joined the store as a clerk. In 1926 the firm became known as Silverman & Bridge, and in 1928 Ben Bridge took over sole ownership. In that year he also relocated from the Joshua Green Building (the 4th Avenue facade; Jacob Young, described below, replaced him) to the new Liggett Buliding (now known as 4th & Pike Building) across the street. He also purchased a Joseph Mayer four-dial street clock for the entrance to his store on Pike.

Since installation, the Ben Bridge clock has moved the least of any Seattle clock. It’s also the only clock still in the possession of its original owner, and one of two clocks (Menashe in West Seattle) still owned by a jeweler. The Carroll clock (described below) may be more ornate, but the Bridge clock is truly Seattle’s gem.

North: Four More

Pivoting left, the view up Westlake was quite different. The road was still open to Pike Street (it now terminates three blocks north at Stewart Street), and the annex of the Hotel Georgian graced the triangle that was later a short commercial building and now the fountain of Westlake Park. The Medical/Dental Building was new and half of its current width. The first view below is from 1926, the second from 1931.

7. Arne Sunde, 1514 Westlake

Sunde was located in the first floor of the Seaboard Building along the east side of Westlake Avenue. Sunde’s clock was installed here by 1916. It was a fancy top two-dial E. Howard design. Sunde was apparently not the first owner of the clock, because it doesn’t match remaining Howard sales orders. The serial number of the movement also is consistent with sale several years earlier. No definite connection has been made, although it could have belonged to Stacy Shown.

Sunde moved to Fourth and Union in about 1942 and was out of business by 1952. The clock had a series of caretakers from the retail storefront, and in 1967 the Alpine Restaurant did the unthinkable and covered the head with a cuckoo clock design for a time.

After moving to Eastlake, it was hit by a delivery truck in 2006. The remnants were rebuilt into a new clock that was recently sent to Canada. Likely it will be refurbished and be available for sale again. This clock should never have left Seattle, as it was a designated landmark.

8. Sam Kaplan, 1615 Westlake

In 1930 Sam Kaplan moved into a storefront not quite visible, in the distance on the west side of Westlake. He purchased a new two-dial clock designed by Joseph Mayer with an Howard-style base and fancy top.

Kaplan was brother of Morris Caplan (see below), and took over Morris’ retail space after he moved to Pike Street. He was father of cartoonist Irwin Caplan.

9? S&W Billboard, Westlake and Pine

I believe that this clock on a billboard for S&W Foods was one of the 16. The photo is from 1931. The clock was a block north on Westlake, at the northwest corner of Pine and Westlake. In later years this space had a Coca-Cola billboard with a clock and later still a Great Northern Olympian passenger train billboard with a clock.

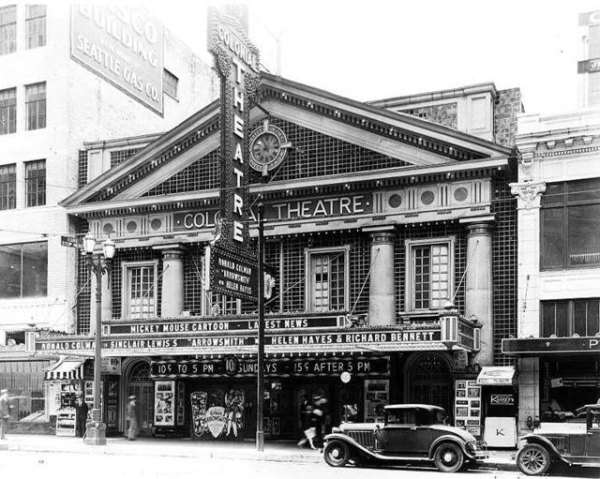

10. Colonial Theatre, 1515 Fourth

Built in 1913, the Colonial Theatre was on the west side of Fourth Avenue just north of Pike Street. The clock was centered near the top of the facade.

West: Eleven to Fourteen

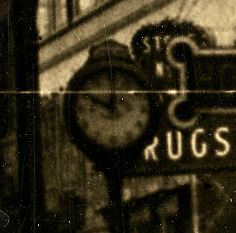

11. Thomas Carroll, 323 Pike

Just west of Fourth Avenue was this new, giant four-dial clock owned by Thomas Carroll. Carroll arrived in Seattle the year before the Great Fire, 1888. He worked for L. P. Smith, the city’s most established jeweler if not the earliest jeweler. Smith had been in Seattle for two decades at that point. During the Great Fire Carroll saved much of Smith’s stock by loading it into wagons and driving it uphill.

Carroll worked for jeweler Fredrick & Company (perhaps with Joseph Mayer’s brother Albert who was employed by Fredrick in 1889), and then by 1896 was in partnership with Winfield S. Morley at 208 Columbia. He continued with Morley for a few years until 1899. From 1900 on Carroll operated an independent store, moving to First and Spring and then in 1913 to the Joshua Green Building at Fourth and Pike.

The clock was installed in 1930, manufactured by Joseph Mayer, and came with almost every option he could get. It was Mayer’s tallest model and had carriage lights on top, ball lights on the bottom, mercury pendulum, and an elaborate bezel. (All it lacked was the extra pedestrian-level timepieces of the eight-dial models.) Carroll later moved this clock around the corner onto Fourth Avenue where Jacob Young’s store had been. The Carrolls closed their jewelry store rather than move when the building closed for renovations in 2008. They decided to donate the clock to Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry, where it has resided since that time.

Before Thomas Carroll had the beautiful 4-dial giant clock that is now at MOHAI, he had this elegant two-dial Seth Thomas. It was originally purchased by Albert Hansen in 1890, the second street clock to arrive in Seattle. It was owned by Burnett Brothers for a few years, who moved it just a few doors north to First and Columbia. By 1913 Carroll had purchased it and moved it here, just west of 4th Avenue on Pike Street. Its whereabouts after 1930 are unknown. At some point the knowledge of this first clock was lost, and the Carroll family’s history now mistakenly refers to the four-dial’s origin date as 1913.

12. Gus Cohn, 310 Pike

In 1915, Spokane jeweler Gus Cohn purchased a stake in Seattle jeweler Harry Silver & Company and moved west to Seattle. Incidentally, Harry Silver had been owner of Seattle’s third street clock (originally owned by William Gilger in 1893). Cohn established his own jewelry shop in 1917, and purchased this two-dial Joseph Mayer clock with lamps on top and sides when he moved to 1421 Fourth Ave in 1925. He moved it here on Pike Street just west of Fourth in 1928. It moved a bit in 1932 to 324 Pike, and then its fate is as yet unknown.

13. Morris Caplan, 206 Pike

Heading further west, Morris Caplan’s huge eight dial clock was installed at Second and Pike just a few months before the Seattle Times editorial was written. Caplan had a two-dial that was hit by a car in 1923, so he upsized with his next clock the following year. He moved it here in early 1930. Caplan moved upstairs in the building in 1932, and the city asked Joseph Mayer to remove the clock after the new retail tenant complained. Mayer apparently retained it in storage because Caplan could not pay the removal charges. It was installed on Dexter by Mayer’s successor after he died in 1937. The clock is currently (2015) under restoration and will be reinstalled on Dexter after it is done.

For a complete, detailed history of Morris Caplan’s clock, read this great article by Paul Middents of the local chapter of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors.

14. People’s Bank, Second and Pike

Morris Caplan’s store was in the west end of the People’s Bank Building. The east end was Second Avenue. On the corner of the building at Second and Pike, an O. B. McClintock clock hung at the People’s Bank. The clock was installed by 1927 and remained there for at least a few years. It may have been installed soon after Joshua Green purchased People’s Savings Bank in 1925 and renamed it People’s Bank and Trust Company. People’s Bank is now part of U.S. Bank.

That clock may be the one that now hangs at Sixth and Olive. In the 1920s there were two in Seattle, one at the Japanese Commercial Bank in Pioneer Square, and this one. There are still two McClintock clocks in Seattle, both nearby those two spots, so I will assume for now that the Law of Conservation is in play.

South: The Final Two

15. Jacob Young, 1433 Fourth

Jacob Young purchased this late Joseph Mayer two-dial clock in 1922 and installed it at Third and Seneca. He moved to Fourth at Pike in 1928, and continued until 1959 though he moved upstairs in the Joshua Green Building around 1950. His clock was purchased by Dean Black, who drove his family into town every weekend to wind the clock. Eventually they moved it to their home, where it was located during the Seattle street clock landmark designation. In 1984 it was acquired by Historic Seattle, rechristened the Earl Layman Street Clock and installed at First and Main. It remains there today on the Seattle Clock Walk, exactly as it looked in the 1920s.

16. Clement Coffin, 1426 Fourth

Clement Coffin moved to Seattle with his family at age 14 in 1888. He apparently left for a gold rush in Dawson, Alaska in 1889 but I have not been able to confirm exactly when and for how long. His obituary seems to describe it being from 1893-1897, but that is not true. He worked for jeweler Robert A. Morse in 1895, in a jewelry store at the northeast corner of Fifth and Pike where the Coliseum Theatre (Banana Republic) is today. Morse, like many men of that time, dropped everything in 1897 and headed to the Yukon gold rush. Coffin bought the store from him. Morse stayed in the Yukon until at least 1911.

In 1909 Coffin moved into the brand new Northern Bank & Trust Company building, now known as the Seaboard Building. That year he purchased an E. Howard two-dial through Joseph Mayer to place at his business. He moved around the corner to the east side of Fourth between Pike and Union in 1927. Finally he moved to Third and Pine in 1933, but there is no record of the clock moving with him.

Clement Coffin died in 1937. The fate of the clock after 1933 is unknown.

More Clocks Before and After

Visible a few blocks down the street there was a two-dial E. Howard pocket watch clock at William Clifton’s store, 108 Pike Street.

Earlier:

And here are the clocks that were within a couple blocks of Fourth and Pike before 1930 but removed prior to the article:

- Winters, in the late-1920s, 621 Pike. Permit signed by Mayer but no photographs yet found to identify the model.

- Segerstrom & Hagen, from 1919 to 1925 or 1926, 1608 Westlake. Mayer late production two-dial type with triple side lamps.

- I. M. Bennett, 1910s at 1536 Westlake near Pine, for part of 1919 at 1527 Westlake. Mayer early production with triple side lamps.

- UPDATE 2/16/2016: Jorgen Nelson owned a clock at 1511 4th Avenue from 1918 to 1920. It was moved to 521 2nd by Isaac Kay. Mayer 2-dial.

Later:

Here are the clocks that graced the intersection or nearby after 1930:

- Goodwins, 310 Pike, installed 1932. Mayer big box top four-dial.

- Green, 307 Pike, installed 1933. Permit signed by Mayer but no photographs yet found to identify the model. UPDATE 2/2/2016: This clock was recently spotted in a photo and identified as a 2-dial “wristwatch” style Joseph Mayer. It looked the same as the Kluh clock in Lacey.

- Burnett Brothers, 4th and Pike nw corner (installed 1936). Large four-dial Mayer clock.

- C. H. Larne, 1529 4th, installed 1938. Mayer designed Howard-style two-dial.

- Pike Place Market Clock, Pike Place, installed after 1937.

- Pre-Florsheim mystery clock, 1421 Fourth, unknown date before 1940.

Further reading:

I’ve shared blueprints of Seattle’s Street Clocks.

I’ve got this insane database of everywhere a street clock is known to have been in Seattle. It’s an open data sheet.

My history of the Menashe clock in West Seattle, with bonus discussion of W. H. Larne.

A couple of my first articles about Seattle’s clocks are rolled up in this discussion of Daylight Savings Time.

My self-guided walking tour, Seattle Clock Walk.

This article includes research by my friend Paul Middents. Here are two great articles by Paul:

- Paul Middents’ history of the Dexter street clock.

- Paul Middents’ Joseph Mayer research page.

Here are my other clock articles:

- The Curious Case of the Central School Clock

- Street Clocks and Stacy Shown’s Showns

- Mayer Brothers in the Klondike

- Seattle Street Clock Inventories, 1920s

- A Broadway clock that tells history, not time (on CHS)

- Time Travel to West Seattle

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.