Cub Scouts in Seattle had America’s very first Cub Scout camp. It was a Paul Bunyan camp, called Blue Ox camp, open from 1930 to 1932.

Camp Do Your Best near Port Angeles was Western Washington’s first summer camp for Wolf Cubs in 1925. But it wasn’t an official Cub Scout camp, because the Boy Scouts of America didn’t officially start Cub Scouts until 1930. When that happened, the Seattle Area Council was first in the country to start a camp for 8 to 10 year olds.

Like many things on this website, the camp is not well remembered, nor its location, theme, nor staff. It is briefly mentioned in the local Scouting history of John J. van Velthuyzen in his “Other Camps” page. Unlike the other camps on that page, though, Blue Ox Camp was a themed event, not an actual place.

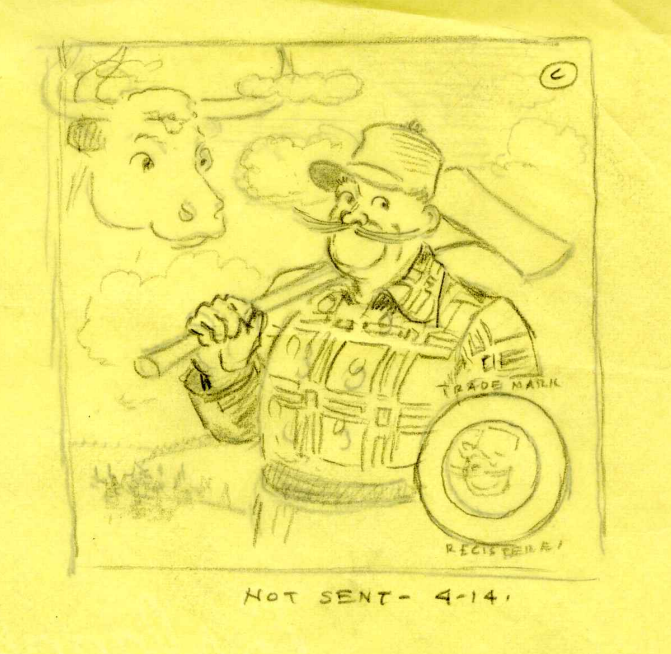

Paul Bunyan camp theme

These days, Chief Seattle Council’s Cub Scout camp is Camp Edward, located north of Monroe and adjacent to Camp Pigott, which is for older Scout troops and Venturing crews.

Camp Edward’s summer camp rotates through a number of themes. This keeps it different and interesting each year as Cub Scouts return for many of the same activities. The themes currently are pirates (Camp Pirate Cove), knights (Camp Excalibur), treasure hunters (Camp Jungle Adventure), and cowboys (Camp Blazing Saddles through 2021, with new name in 2025).

Likewise, Blue Ox Camp used a theme to lure cubs out of their homes for one to eight weeks of summer camp. Blue Ox Camp had a lumberjack theme. It used the newly popularized myth of Paul Bunyan.

Paul Bunyan origins

We don’t know exactly when or where lumberjacks began sharing tall tales of Paul Bunyan. Probably Wisconsin in the 1880s, per Michael Edmonds in Out of the Northwoods.

So far, the first known publication of a Paul Bunyan story came in 1904 in Duluth, Minnesota. Over the next two decades new stories emerged and morphed, and were captured in papers and advertisements from the Midwest to the West Coast. They even traveled to Europe during World War One with drafted U.S. Army soldiers.

The names of most of the characters come from lumber advertisements written starting in 1914 by W. B. Laughead. Laughead’s stories and characters became interwoven with stories told by lumberjacks and woodsmen. Later writers adopted them and expanded on them. The stories began leaving the camps and entering print.

The two Paul Bunyan tomes

By the time Blue Ox Camp opened, Paul Bunyan had crossed over into mainstream American culture. Popularization came in 1925 via two books written simultaneously near Seattle, Washington, both titled Paul Bunyan.

The first book, released at the end of 1924, came from academic folklorist Esther Shephard. Shephard completed a master’s thesis in 1921 at the University of Washington on frontier folk tales. She then expanded a section on Paul Bunyan into a book all about him, collecting stories from written sources across the country and pairing them with tales from local loggers. In 1924, she self-published this under the title Paul Bunyan. The book was picked up the next year by major publisher Harcourt, later illustrated, and kept in print to this day. Shephard lived west of Seattle across Puget Sound in Suquamish, and wrote book reviews and poetry for the Seattle Times. Later she returned to the UW for a PhD and became a professor.

Then in mid-1925, itinerate lumberjack and prospective author James Stevens collected the stories he learned at war in France, in American lumber camps, and in interviews of old timers in western Washington and Oregon. Like Shephard he simply titled his book Paul Bunyan. Stevens had been familiar with stories of Paul Bunyan for many years, and like other loggers slowly expanded the tales on his own. After reading plagiarized publication of Laughead’s stories in Century Magazine, Stevens decided to try writing his own. He started with a feature in H. L. Mencken’s new magazine American Mercury, published six months before Shephard’s book. Mencken’s publisher Knopf loved it and contracted Stevens to write a full book, which he wrote in Tacoma in the few months before Shephard’s book was printed.

Contrasting Paul Bunyan books

While trying to make the stories fit to read, both authors transformed them in seemingly opposite ways. Both authors chose light hearted retelling of the backwoods stories. But Stevens, the former logger, faked an air of credibility and provenance while embellishing stories and making up new ones. In contrast Shephard, the academic, tried to write in the style of a logger while mixing written stories with folk tales and restructuring them into a linear chronicle of Paul Bunyan’s life.

Both were successful. Together they took the stories out of the woods and put them into homes and libraries across America.

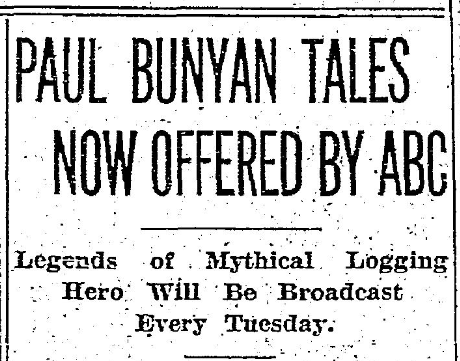

In 1929, Seattle-based American Broadcast Company radio network (unrelated to current ABC) commissioned James Stevens to write 35 stories for evening shows. Their Seattle channel was KJR 970 AM. They were recorded in Seattle, performed by Burton James and the Seattle Repertory Players, and was broadcast from January until at least August. ABC went through financial collapse during this period, and it’s not clear if all of the episodes were scripted and performed.

Inspiration for the theme of Blue Ox Camp surely came directly from Stevens’s radio show, which was a continuation of the popularity of his book and Shephard’s.

Paul Bunyan crosses over

In 1927 a review of a new children’s book about the myth of Paul Bunyan said, “The mythical Paul is just the type that would appeal to the mind that is just a little but not much too old for the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale… The Bunyan legends are essentially of the same sort of stuff from which the familiar fairy tales are made… Paul Bunyan is New World folk lore. The Bunyan exaggeration, the Bunyan direct and cumbersome humor scores instantly with the juvenile mind.”

That age range was exactly the target for Blue Ox Camp.

Camp location

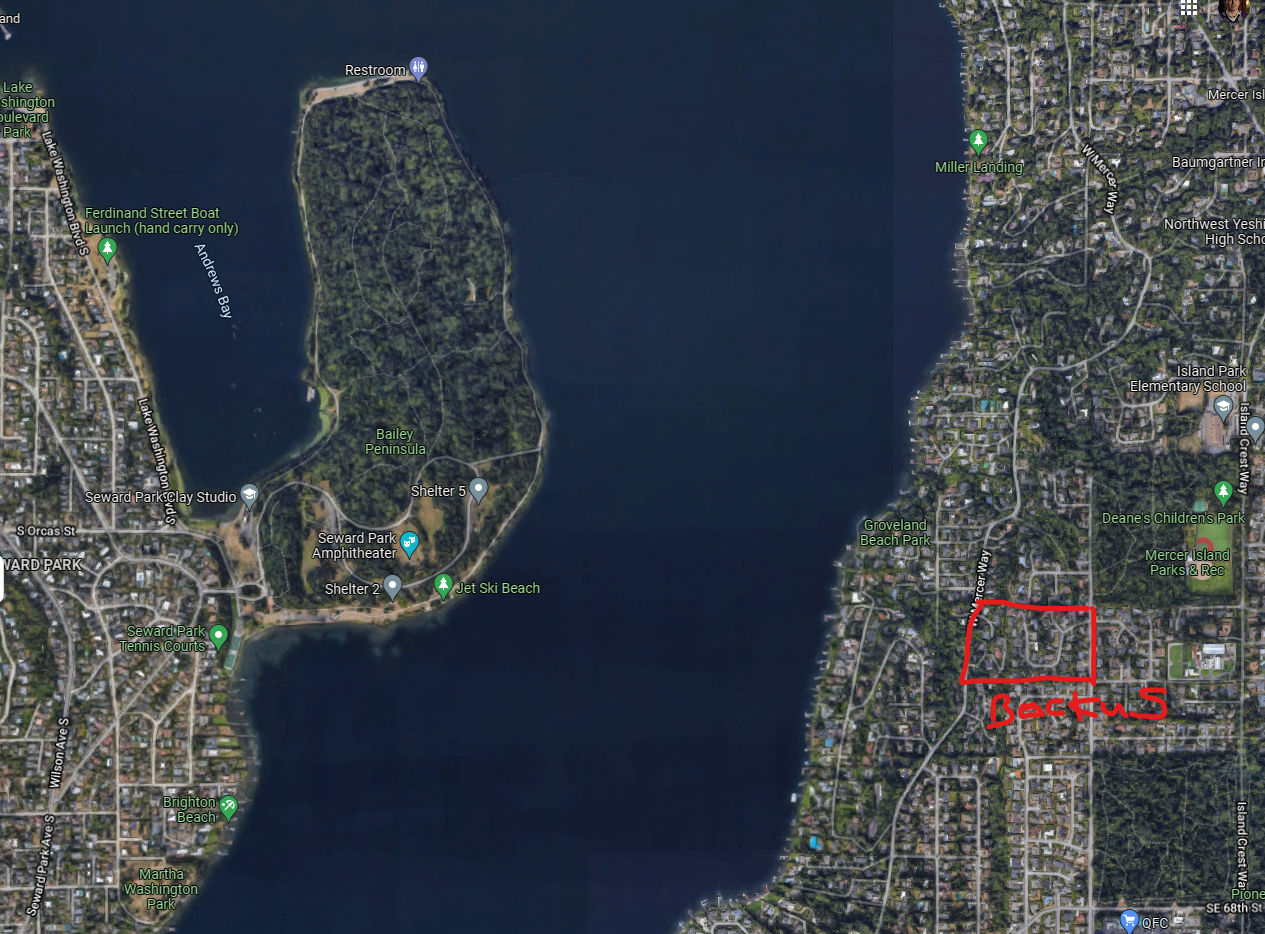

Blue Ox Camp was held on Mercer Island, which lies in the middle of Lake Washington to the east of Seattle on Interstate 90. Indeed, at that time the north end of the island was known as East Seattle. The interstate freeway and its bridge didn’t exist back then, of course, so Scouts got there by mosquito fleet passenger ferries.

The Cub Scout camp used existing facilities. It occupied Camp Backus from 1930 to 1931, and then Camp Rotary in 1932.

Camp Backus was donated to the Boy Scouts’ Seattle Area Council in 1925 by Manson Franklin (M. F.) Backus, head of the National Bank of Commerce, and his wife Elsie Backus. It covered 20 acres.

By 1967 the council had outgrown Camp Backus. They sold the land to raise funds to build Camp Brinkley on the Cascade Scout Reservation. Brinkley was recently rebuilt as Camp Edward, named after Edward J. Perry, and fittingly dedicated to Cub Scouts summer camp.

The Camp Backus property was purchased by Austin-Wilkins Company. Several months later the company sold the property to Byron Emory, a 1960s Mercer Island developer. He platted it as the Dawn Villa addition, sibling to nearby Dawn Terrace and Dawn Vista. He opened a model home at 8370 SE 61st by architects Paul Burckhard and David Hermans.

After the 1931 season, Blue Ox Camp moved in 1932 to Camp Rotary. This land was purchased in April 1925 by Rotary Club for Seattle Area Council Scouts, also 20 acres in size. It was “east of the main island road, one mile south of the county dock on the west side of Mercer Island, and includes twenty acres of wooded land”.

Camp director H. G. Clark

The first camp director was Harris Glover Clark, who played the role of Paul Bunyan in 1930. In his late 20s, Clark was an Eagle Scout and an experienced Scouter. He worked as field executive for the Seattle Area Council, and ran camps for the council’s Scouts in Alaska. He served as Scoutmaster for troops 5 and 12. Prior to becoming field executive, he ran the Scout shop and was an executive assistant. Later he took over as camp director at Camp Parsons in 1937, the year that the Cub Scouts’ Camp Meany was established next door.

Clark was married in early 1931, perhaps the reason he only worked at the camp in 1930.

Camp director Walt Woodward

Walt Woodward took over as director in 1931. He is the most famous, and for different reasons was also the most newsworthy in 1930. At the time, Walt Woodward was a UW pre-med student who made the sports pages as a long distance runner. He was an Eagle Scout. He staffed Blue Ox Camp as assistant director in 1930 and was director in 1931 and 1932, playing the role of Big Swede at all three.

Perhaps due to the popularity of Blue Ox Camp, Woodward was hired by the Bon Marche to create a Scout-themed activity area for boys called the Corral Club in 1932. He took the roll of Ranger Bill and led activities such as woodcraft, leather work, airplane and ship model building, photography, swimming, boxing, wrestling, baseball, and track.

After college Walt became a reporter and journalist. Before and during World War Two he was the editor of the Bainbridge Review. He used that forum to strongly protest the federal government’s imprisonment of Japanese Americans, and he was one of the few editors who spoke out.

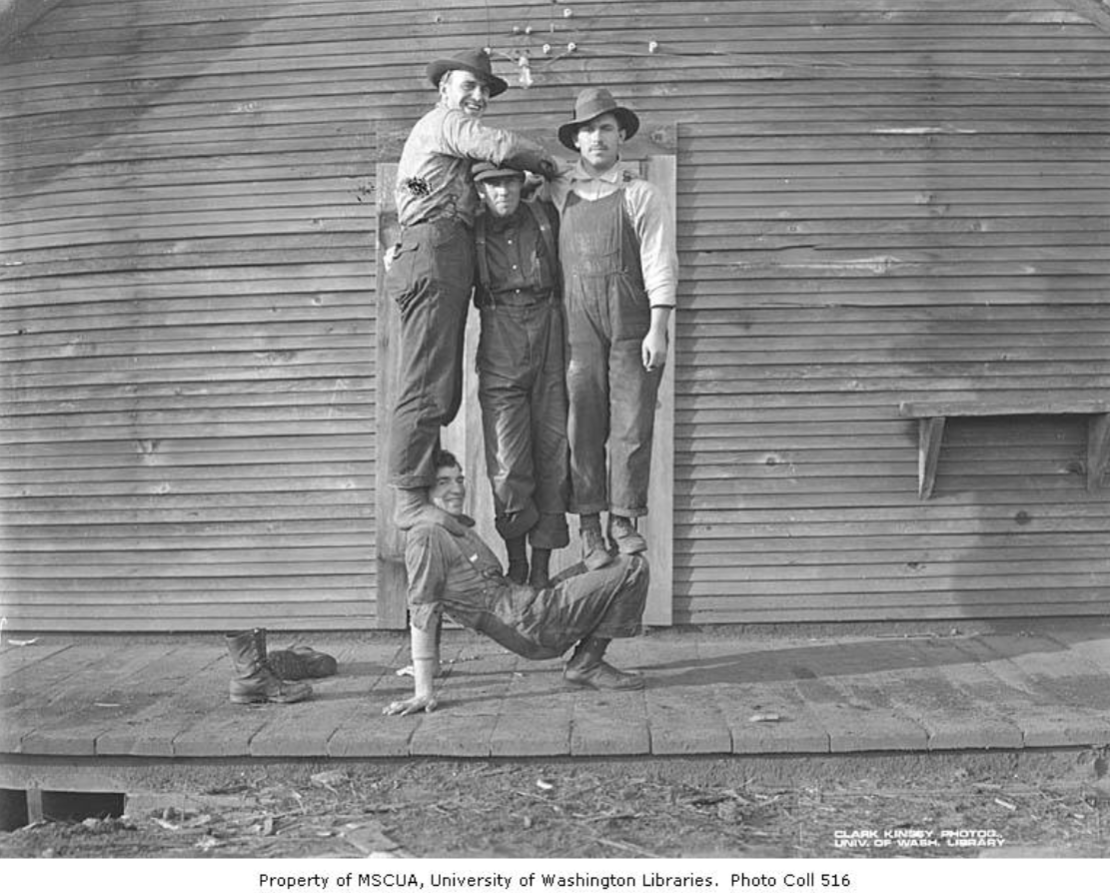

Camp staff

Other staff in 1930 were Laurence “Larry” Guise, William “Bill” Millington, and Judson “Jud” Hubbart. Millington continued in 1931 as assistant director.

Millington attended Garfield High School, where he was in a cross country ski team with other Scouts. He graduated in 1931 and entered the University of Washington. After college, he entered the Marines and learned to fly at Sand Point Naval Air Station. He became a flight instructor in the Marine Aviation Corps, and then led Corsairs in Squadron VMF-124 against the Japanese military in World War Two. Before retiring from the Marine Corps, Millington rose to Brigadier General. He later was president of the Seattle chapter of March of Dimes and Seattle Rotary, and led many other organizations.

Guise became a merit badge counselor and council leader after high school. He worked at Boeing’s airplane plant in 1940.

Hubbart attended the University of Washington as well. In 1935 he became a reporter for the Centralia Daily Chronicle. He spent a year in Tokyo working at the independent paper the Japanese Advertiser, and in 1937 went to work for the Associated Press in New York. He returned to Seattle to take an advertising job for Chevrolet, then became an officer in the Navy during World War Two. Hubbart remained in the Navy Reserve after the war, rising to captain. He returned to advertising and helped run Boeing’s ad campaigns into the 1970s.

Camp Staff – second and third year

Millington and Woodward were joined by their Garfield High pals Fred Thieme and Richard “Dick” Brookbank in 1931. Woodward’s coworker Julian Johnson joined staff in 1932.

Thieme attended Garfield with Bill Millington. They graduated together, and started the UW cross country ski team. Thieme was its first president. (More details on the ski team.) Impressively, in 1937 Thieme and another guide were the first to ascend Mount Rainier via the Sunset Amphitheater. Like Jud Hubbard, Thieme served as an officer in the Navy in World War Two. Then he returned to school for a PhD in anthropology. Subsequently, from professorship he entered university administration and he eventually rose to president of the UW.

Brookbank graduated from Garfield in 1932 and entered the UW. After graduating, he went to Munich, Germany to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. He returned to Seattle in 1939 and went to the UW again, this time as a German professor. During World War Two he joined the US State Department’s Office of Foreign Relief and Rehabilitation Operations (OFRRO), and worked with refugees in Italy, presumably German speakers. After the war he had a leadership position with refugee services at the United Nations. He returned to the US to teach German again at Rice University. In the 1970s he led the Seattle Opera endowment.

Johnson worked with Woodward at the Bon Marche’s Corral Club prior to joining Blue Ox Camp staff. He was a salesman for the Bon Marche but had a penchant for leatherworking and enjoyed all scoutcraft. Johnson took over as Ranger Bill in September 1932, signaling Woodward’s exit from Scouting after graduating UW. Later, Johnson moved to Los Angeles and by 1940 he worked for the Los Angeles-Seattle Motor Express freight trucking company.

Who played what character when

| Staff | Character | Years |

| Harris G Clark | Paul Bunyan | 1930 |

| Walt Woodward | Big Swede | 1930-2 |

| Bill Millington | Johnny Inkslinger | 1930-2 |

| Larry Guise | Hot Biscuit Slim | 1930 |

| Jud Hubbart | Shanty Boy | 1930 |

| Fred Thieme | Mark Beaucoup | 1931-2 |

| Dick Brookbank | Shanty Boy | 1931-2 |

| Julian Johnson | Old Doc Cowhide | 1932 |

Paul Bunyan camp characters from Laughead

The name “Big Swede” was used to refer to many different characters in various stories. Presumably this was meant to be James Stevens’ character, Paul Bunyan’s foreman, whose real name was Hels Helson. He was a giant too, but not as big as Paul Bunyan. In his primary story, he lead the logging of the Mountain That Stood on Its Head. Hels and Paul had a disagreement about how to do the logging, but worked it out in a huge battle which Paul won. Hels continued as his foreman happily. In other stories “Big Swede” is used to refer to “Big Ole”, Paul’s blacksmith, or to an unnamed cook. There were earlier stories with Big Swede as foreman.

According to James Stevens, Johnny Inkslinger joined camp because Paul Bunyan was spending so much time keeping track of the books and could no longer work with the timber. “Inkslinger” was a pejorative term used by loggers to refer to bookkeepers and clerks, but in this case it became a family name: John Rogers Inkslinger. Like Hels and Paul, he was a giant. But he was educated, and at work surveying of all of the American west. Johnny joined him to keep his books and give advice on efficiencies. This character was invented by W. B. Laughead in 1914 and appears in both Shephard and Stevens’ books.

Characters from Stevens

Hot Biscuit Slim was the chief cook of Paul Bunyan’s camp. He joined when his father, Sourdough Sam, blew his arm and leg off with explosive sourdough. Sourdough Sam was invented by Laughead, but Hot Biscuit Slim was James Stevens’ invention.

Shanty Boy had an entire chapter devoted to him in Stevens’ book Paul Bunyan. He was the greatest of the great performers at the evening campfires in Paul Bunyan’s camp. Shanty Boy could tell great tales, and dance with every part of his body, and his songs could pull out every emotion. He sang songs like Jack Haggerty, Island Boys, John Ross, and Bung Yer Eyes. He could also exaggerate like none other, right up to the brink of it being a lie. Shanty Boy was an invention of James Stevens.

Mark Beaucoup was one of Paul Bunyan’s best loggers, “a mighty man with both ax and pike pole”. James Stevens invented this character when he was in France during World War One.

“Old Doc Cowhide” was not a character in James Stevens’ book or any other Bunyan story. The camp doctor was Johnny Inkslinger. Back in 1930, a doctor would carry their instruments and cures in a cowhide leather satchel, possibly the inspiration for the name. Or perhaps he was a cowboy dressed in cow hide vest and chaps.

(If you happen to have access to this article via a college or private school account, let me know if Stevens explained Hot Biscuit Slim, Big Swede, or Shanty Boy.)

Camp activities

In 1930, camp took place in July during two, two-week sessions. The following year, it expanded to eight one-week sessions. In 1932 this was cut down to just four one-week sessions, perhaps due to availability of director Walt Woodward. Some Cubs continued for multiple consecutive sessions.

Per the July 4, 1930 Seattle Times, the camp had “many of the features of a lumber camp.”

Program activities described in the Seattle Times and Seattle PI included, “games, hiking, swimming, campfire, and, far from least, eating.” (7/31/1932 ST) Also water sports and woodcraft.

Presumably activities at the Bon Marche’s Corral Club were also done at camp, like leatherwork and model building. And with the number of sports played both at Camp Do Your Best and at the Corral Club, there must have been plenty at Blue Ox Camp. Sports such as boxing, wrestling, baseball, track, and maybe even golf and tennis.

Blue Ox Camp ended in 1932, perhaps due to Walt Woodward graduating from the UW and needing a real job during the Great Depression. After Blue Ox Camp, Cub Scouts met at Camp Parsons near Brinnon on the Olympic Peninsula for two or three weeks during the summer when no older Scouts were there. In 1937, Camp Meany was dedicated to Cub Scouts adjacent to Camp Parsons. It is now the east half of Parsons.

Acknowledgements

Tall Timber Tales is the best original research chronicle of early publications.

And several key texts:

- Esther Shephard’s 1924 Paul Bunyan

- James Stevens’ 1925 Paul Bunyan

- Michael Edmonds’ 2009 Out of the Northwoods

Further Reading

- Cub Scouts began in Port Angeles (part 1 of this series)

- Camp Do Your Best (part 2)

- Wolf Cubs Lost at War (part 3)

- What they sang at Blue Ox Camp (part 5)

- Cub Scout Alphabet

My other articles on early Seattle Scouting:

- The Start of Scouting in Seattle

- Seattle’s first patrol leaders

- Seattle’s first Eagle Scout

- Elmer Katayama at Camp Parsons opening

- George Nakashima and Scouting

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.