Any historian would be satisfied with the simple anecdote of Jennings and his Jennings’ Addition street names. It is a relative spoil of humorous riches hidden in old archives. But I stumbled upon another fun anecdote for Arthur Jennings in Seattle: a spite mound.

Led to water by the old Seattle P-I, with records from the Seattle Municipal Archives, and with further Washington State Archives records dug up by my friend Valarie Bunn, I bring to you the story of Mount Jennings. It’s the two-part conclusion to our series.

This is part 6 of a 7-part series Summiting Mount Jennings. You could start at part one.

Spite mounds carved from nature

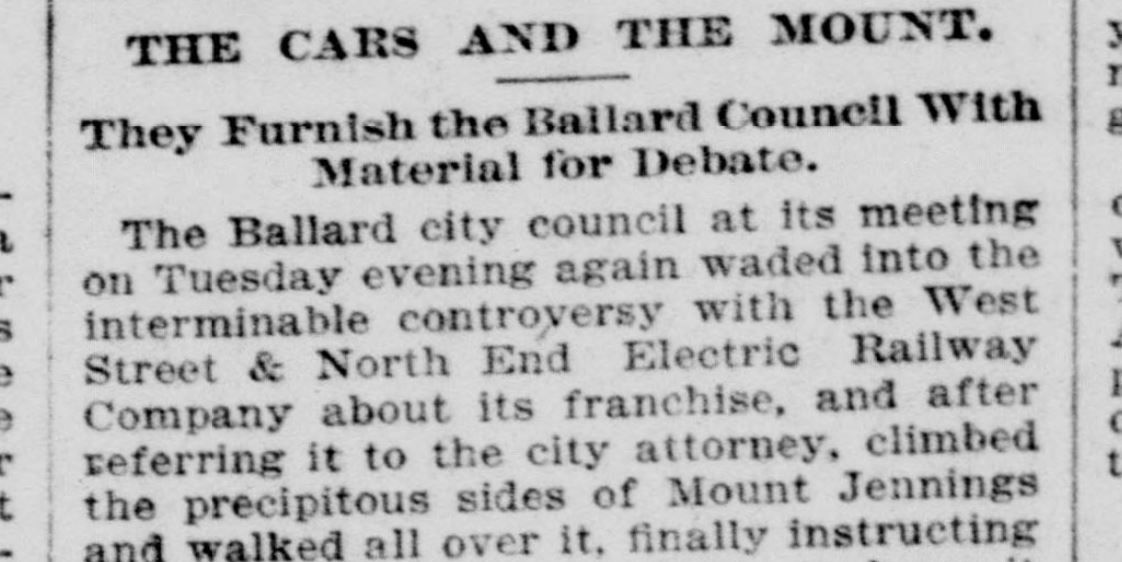

Mount Jennings, named after A. B. Jennings, can’t be found on any current map of Seattle. If you were back in early Ballard, though, it was an infamous landmark. The Seattle P-I described its origins simply for us on May 3, 1894:

When the city graded Ballard avenue Jennings got an injunction restraining the city from removing the earth from the front of his lot. There is in consequence an unsightly obstruction, called Mount Jennings, extending half way across the north end of Ballard avenue, which impedes traffic and is a damage to Jennings’ property as well as to the city.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 3, 1894, p5.

The landscape in downtown Ballard doesn’t at first seem altered by man. It’s hard to imagine an impassable mound anywhere in Ballard. It’s all a gentle slope up from Shilshole Bay now. The steepest piece is the grade change on 22nd Ave N.W. from Shileshole Ave to Ballard Ave. No buildings are raised above the road.

But the roads are too perfect, a fact that’s particularly obvious on Leary. When a road in Seattle has a constant upward slope over so many blocks, it’s a clear reveal that there used to be high and low spots that were scraped away.

Ballard scraping by R. H. Thomson

Soon after Ballard incorporated in November 1889, they hired R. H. Thomson to survey the city, plan street improvements, and undertake other engineering work. Thomson is famous for later leading the regrading of Seattle, including leveling Denny Hill.

Thomson was Seattle’s city surveyor from 1884 to 1886, then worked as chief engineer of a local rail line from 1886 to 1889. Every biography of Thomson and even his 1950 autobiography next skips forward a few years to 1892 when he returned to Seattle again as city engineer.

Missing in all accounts of his life is his work for Ballard for at least two years from its inception: 1890 to 1891.

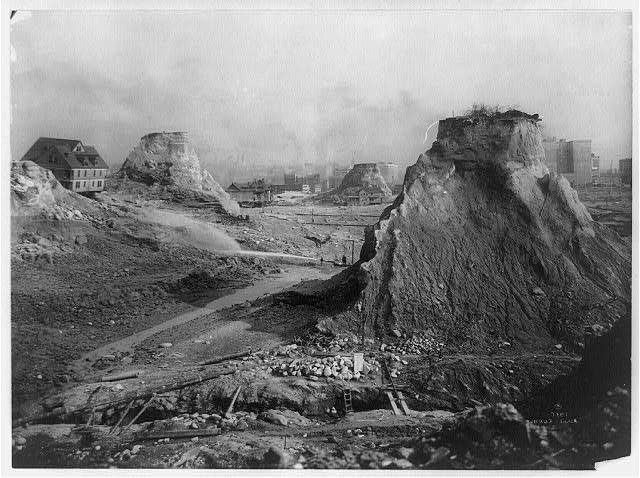

Spite mounds were budget buttes

An iconic image of the Denny Hill regrade features pinnacles of earth with a residential yard perched atop. From the beginning they were called “spite mounds” or “spite hills“, and there was apparently immediate misconception in 1910 that the owners were in protest to the regrade.

It’s an understandable mistake. Over beyond Broadway and First Hill, property owners honestly fought against the 12th Avenue regrade in 1908. But as David Williams describes in his book Too High and Too Steep, the major papers – Seattle Star, Seattle Times, and Seattle P-I – all made pains to explain that Denny Hill’s spite mound owners were only protesting the high cost.

Everyone chipped in to pay for the lowering of public land, but each individual property owner had to pay for their own vertical slice to be washed out to sea. As was the case in other regrades, some property owners were remote and didn’t know they were being asked to pay. Others were adamant that a scam was being perpetrated by City Engineer R. H. Thomson and wanted to pay less.

These buttes were budget problems: unable to get money from remote owners, and unable to convince some owners to pay without a court hearing. But none of the owners actually wanted to stop the regrade.

Always spite, not always a spite mound

Thomson should have expected difficulty resolving the grade of at least a small percentage of properties of Denny Hill.

Because he had experience with protests. First he watched as the grades he surveyed for the city of Seattle from 1883 to 1886 were protested by property owners one by one, every time.

But even more, he had personal experience as the city engineer in Ballard in 1890. His very first regrades were met with protests over financial costs.

And in one Ballard case the fight went all the way through the courts, and Thomson lost.

Mounting a spite mound

That Ballard case was the civic embarrassment called Mount Jennings. It was an earlier, if less lofty and dramatic, example of a budget butte. It was a remnant of one of Thomson’s Ballard regrades, right in the middle of Ballard Avenue, in the heart of the new city.

Arthur Jennings was a remote owner, but he knew about the assessments and began his fight at the start. Jennings protested the cost, he protested the necessity of the regrade, he protested its damage to his property, and he protested the right of Ballard to charge him since his ownership predated the city.

His argument against damages was a winner, and his mound became a short-lived landmark of civic failure.

Like the Denny Hill protesters, though, he was just budget-conscious. Once the specter of payment went away, he was happy to have the street lowered in front of his building.

In the final part of this series we’ll learn the details of Mount Jennings.

Further reading

- Previous: Ballard Streets named by A. B. Jennings, part five of Summiting Mount Jennings

- Next: Finding Mount Jennings, part seven and the finale

- Rebuilding Seattle after the Great Fire

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.