Construction of Seattle’s Montlake Bridge finished in 1925. In the 70 years before that, there were at least a dozen different ways to cross that land between Lake Union and Lake Washington.

I appeared on SPACE 101.1 radio in Seattle talking about Montlake crossings on March 5, 2023. You can listen to it on the Cascade of History podcast.

Portage trails – the end of 10,000 years of use

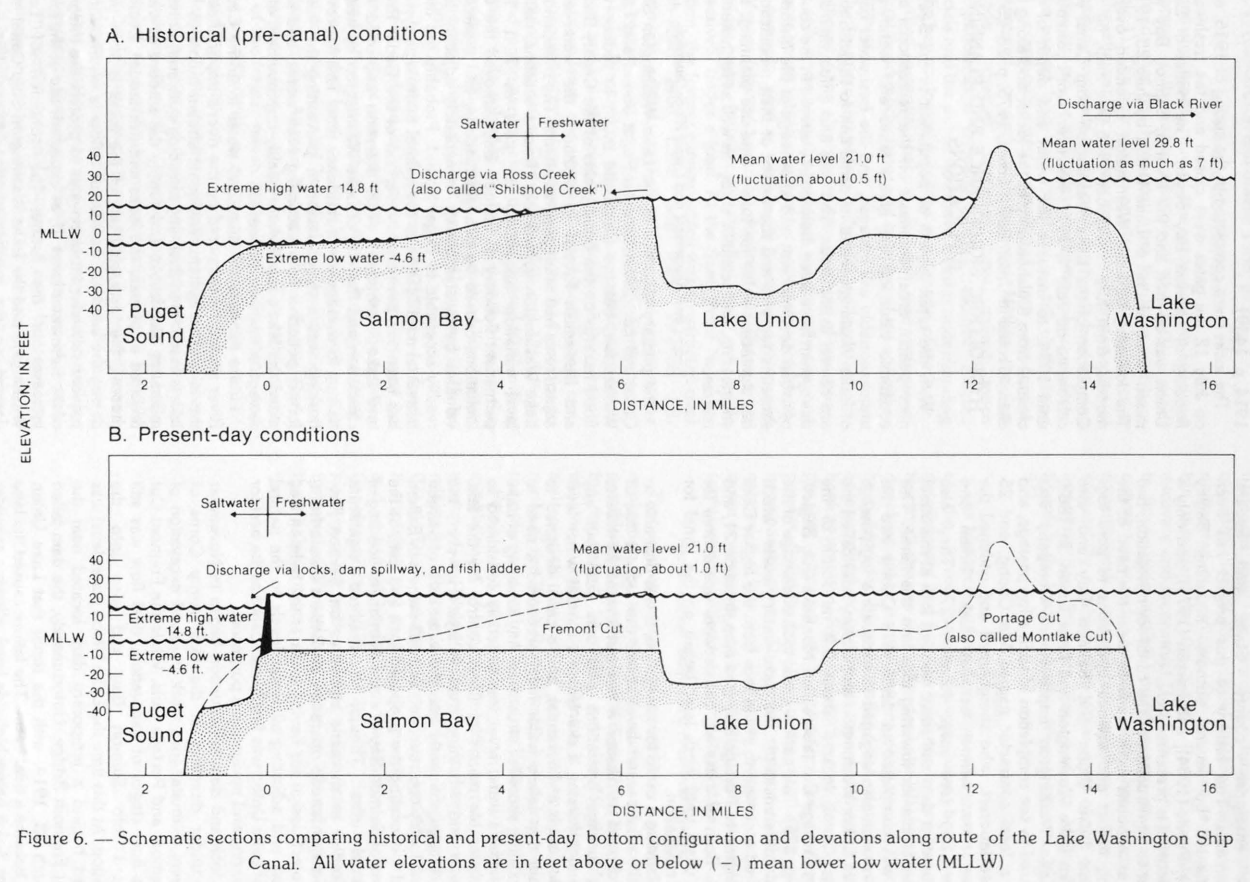

Lake Washington (Big Lake), was quite higher than Lake Union (Little Lake) back before first contact, when native people like the Duwamish and Suquamish traveled frequently between the lakes. A narrow stretch of land about 300 yards wide held Lake Washington back from Lake Union. Water flowed out of Lake Washington to the south on the Black River, so it would be a rare flood to see water course over the isthmus. It happened on occasion, though, forming a small creek.

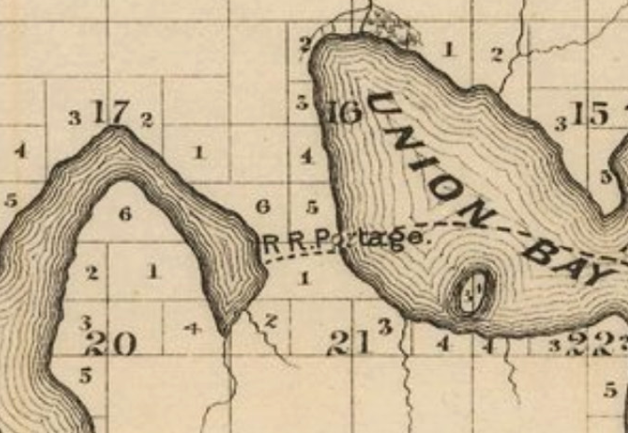

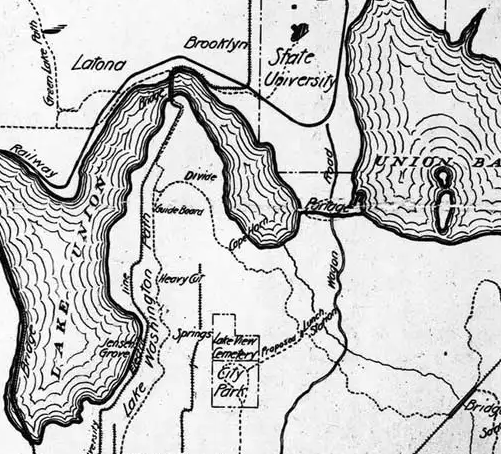

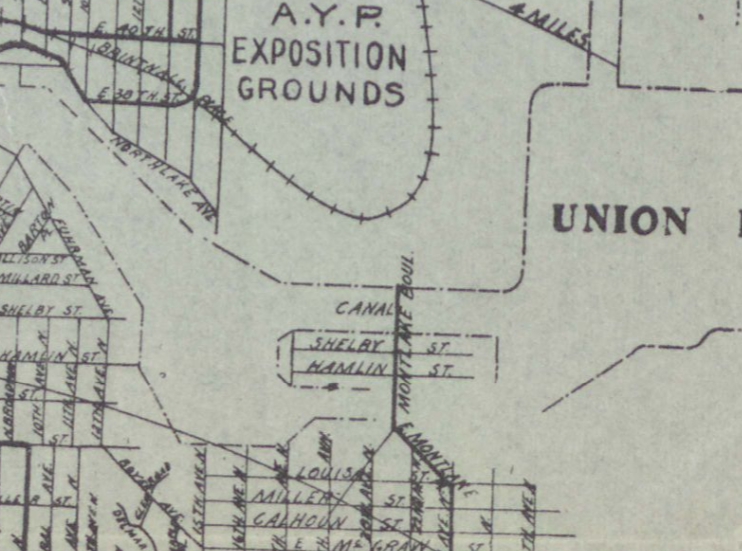

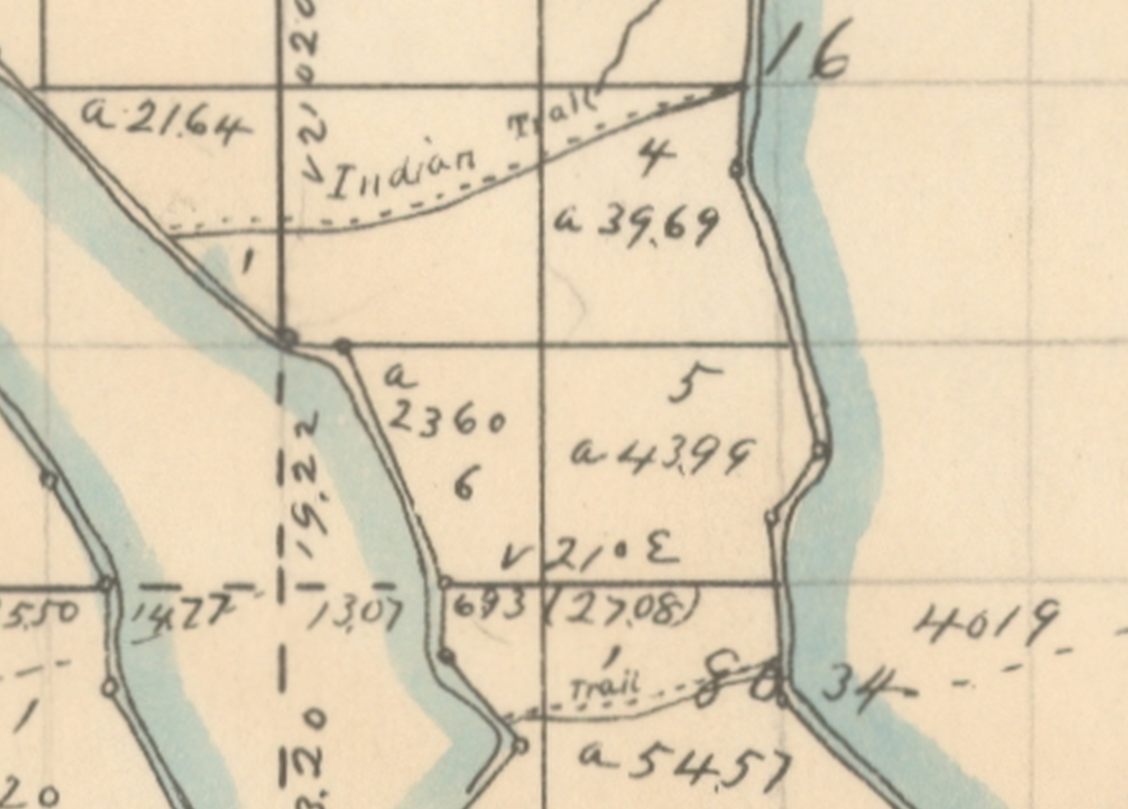

We refer to this stretch of land as a portage — as the portage — because of the two trails used by native peoples running east to west across it. They had a more specific name for it, stəx̌ʷugʷił or “Carry a Canoe”, part of the water trails that took them between settlements and to the backcountry. The trails are visible in the 1855 survey by Phillips and Strickler for the US federal government’s General Land Office, published as a map in 1856 (below). The sparse geographical notes that accompanied the survey of township edges and its lakes also mention the portage trails.

“Spring, Branch 2 links wide. Courses from west, at 9.00 chains north. Spring Branch 1 link wide, courses from S.W at 21.90. An Indian trail strikes lake, courses from west… [several entries later] At 50 links Indian trail strikes the lake, courses from west.”

1855 survey notes, BLM GLO

Other connections

These trails of the portage continued to serve the needs of native people after the arrival of white settlers, who came to claim chunks of legally unowned land. And the isthmus served as a north-south connection for the lake shores and ridges and the land beyond.

Along with the well-worn east-west paths, it seems like there should also have been a north-south trail. Maybe it was not much more than an animal track, though.

It’s important to realize that for centuries, for millennia perhaps, people were basically concerned about how to cross this piece of land from west to east and back. Contrast that with the past hundred years, when the difficulty has been getting between the south and north, particularly when the bridge is up.

Also, although the land had legal white ownership as early as 1854, native people did not disappear from the portage. For decades, the home of Cheshiahud and Tleebuleetsa was just southwest of the portage. And Dr. James Zackuse’s cabin was across Portage Bay from the west side of the portage. Both homes are visible in many photographs, and both families played significant roles in the early stories of Seattle the city.

Images of portage trails

1860s: Pike picks at the isthmus peak

The Washington Territorial University, now University of Washington, was authorized by the territory government and formed in early 1861. The territory set aside lands in 1854 and granted then in 1861 to fund the university’s development and operations, including the portage between lakes Union and Washington, with land to the south and much more to the north of it. The land to the north became the new home to the university in 1895 when Denny Hall opened.

The portage and land south was was given to Harvey Pike as payment quite a bit before that.

Harvey Pike and his father John Pike and their crew constructed the first buildings for the University of Washington from 1861 to 1862, on a knoll above the settlement at Pioneer Square. Their work included a main building, boarding house, and home for the president.

(I wrote about John Pike for Capitol Hill Seattle Blog in 2017. However, I incorrectly described John Pike as the owner of the portage land. I also incorrectly credited him as the eponym for Pike Street. Instead, as I will describe in an upcoming article on this site, Harvey Pike was the eponym.)

Pike starts digging

Sometime in the next decade, Harvey Pike went to work trying to dig a ditch between the lakes. He dug at the narrowest part of the portage, to the south near the southern native trail.

Most references to the digging say that the work started in 1860. For example, the current Portage Bay article on Wikipedia, but also at least as far back as Edmund Meany’s 1925 book The Origin of Washington Geographic Names. That doesn’t sound right, though. Prior to legal inception of the university, this was state land. You can’t just go terraforming public property.

The land transferred to Pike on June 12, 1861, which seems like the earliest date the digging could have happened. David Williams’s article about the digging is appropriately broad, saying “sometime in the 1860s”.

Working backwards, the work certainly wrapped up prior to 1871, when Pike formed the Lake Washington Canal Association with Robbins, Fairchild, Humason, and McNaught. Pike deeded land to that company after its formation.

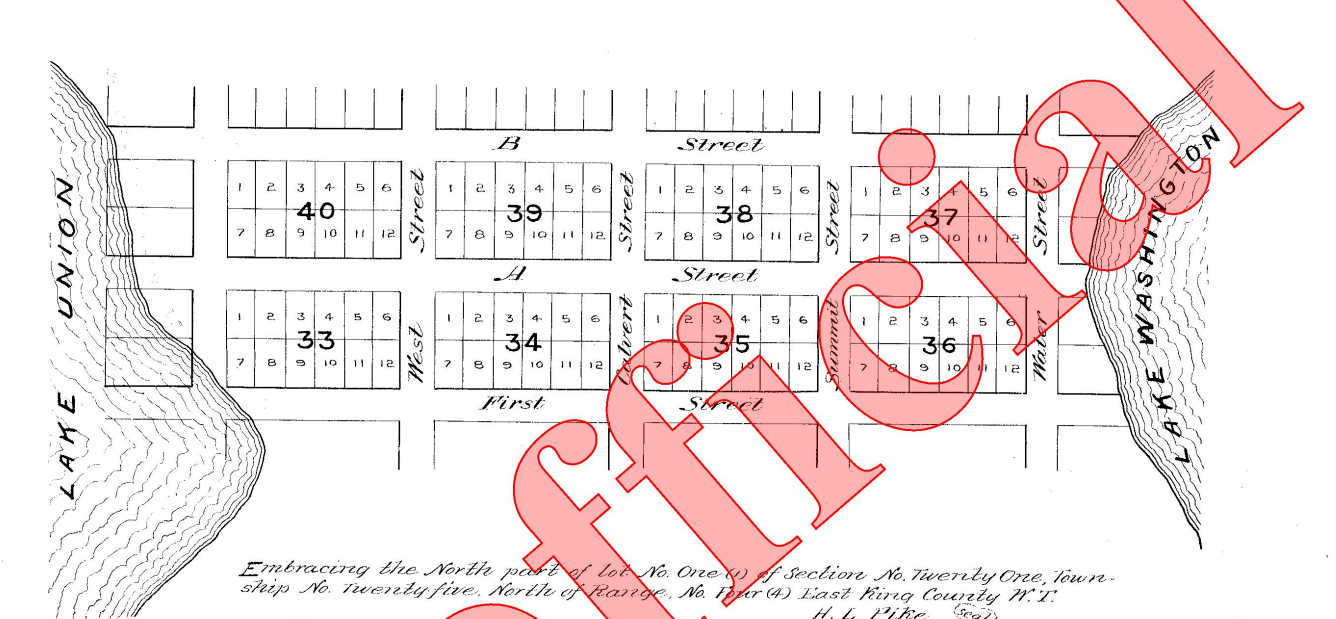

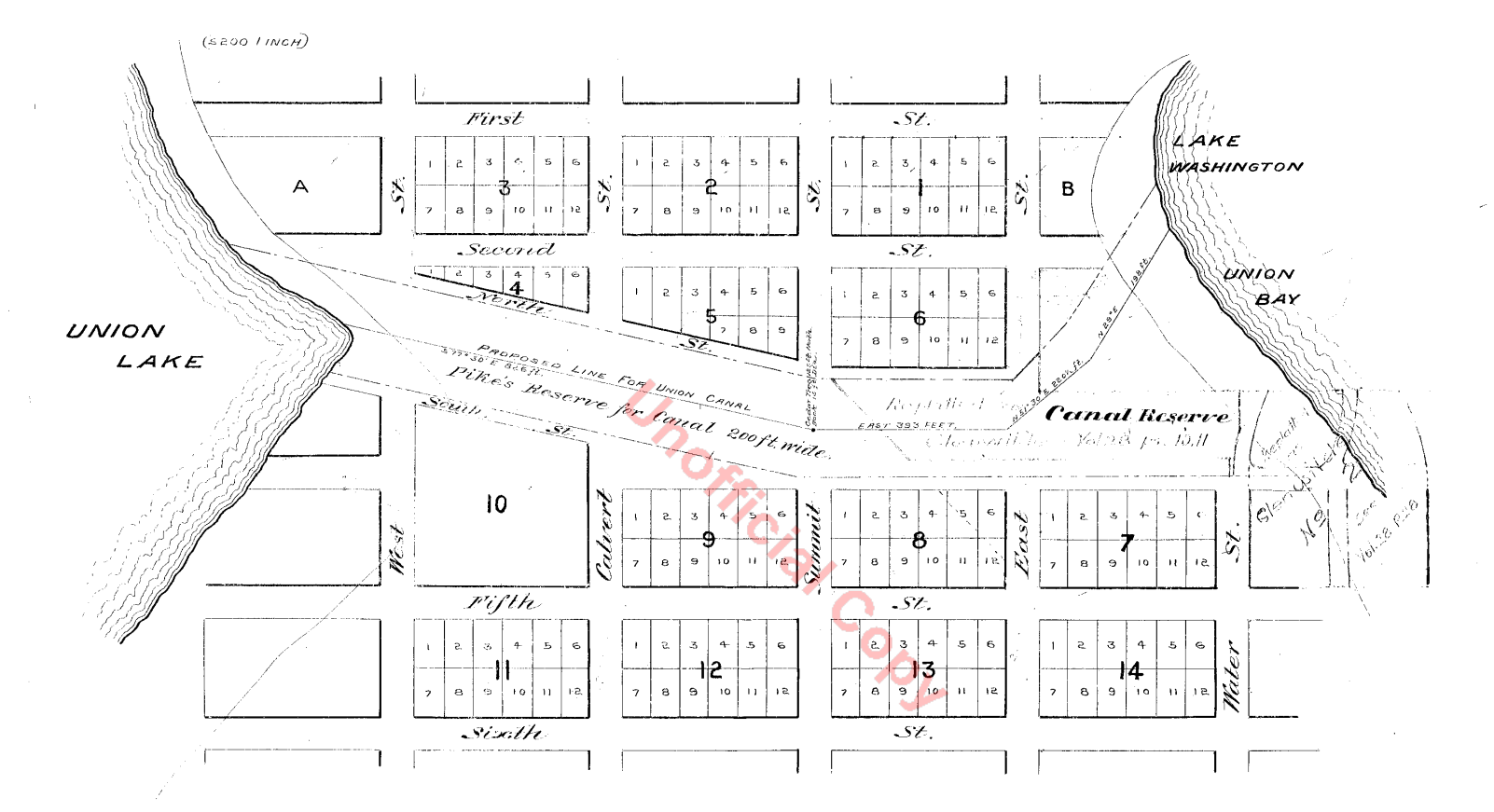

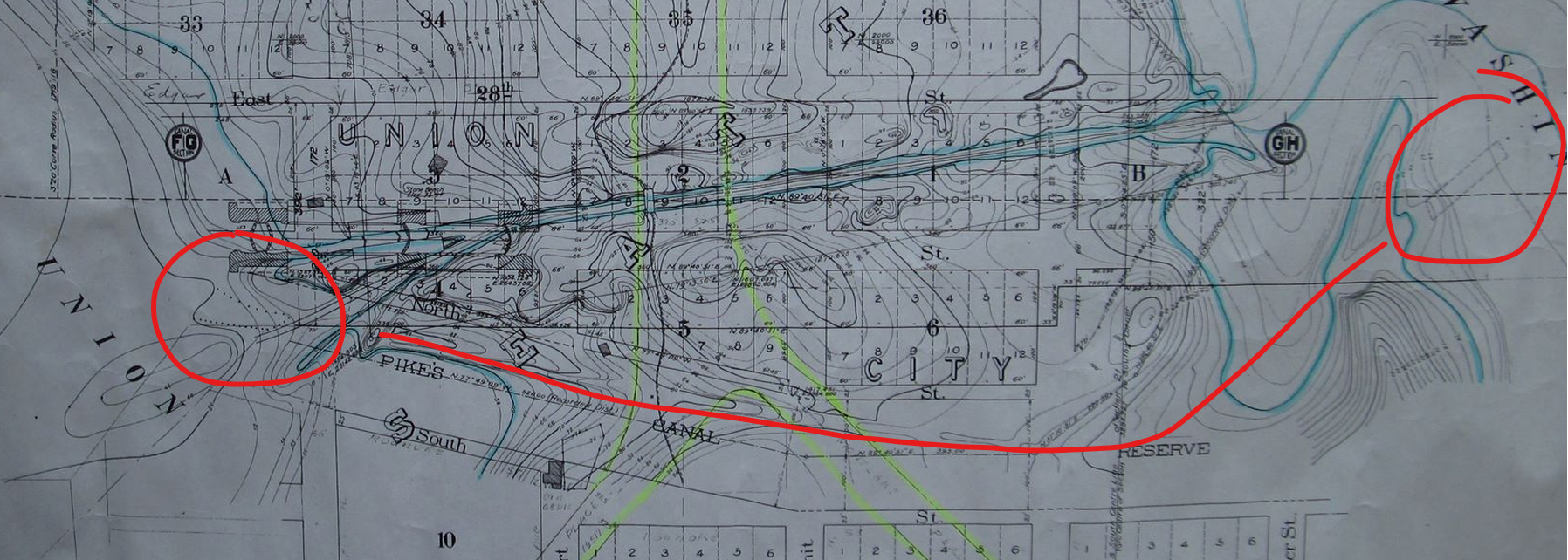

The digging plausibly could have been part of a publicity stunt for his 1869 plat of Union City, which set aside land for a canal, called the Canal Reserve. But Pike leased land for a canal to Henry A. Webster on May 25, 1868 for five years. So the reserve more likely was set aside for the leased land, and indicated a route that Pike already decided.

One source hints that the date was after late 1864. In a March 21, 1916 Seattle P-I article, UW history professor Edmond Meany spotlighted pioneer George P. Wilson. Wilson came to Seattle in late 1864 and worked clearing stumps from the new cemetery, now Denny Park. He recalled Harvey Pike, David Denny, and others heading past the cemetery on their way to locate a good spot for a canal through the portage.

In summary, it’s safest to date Harvey Pike’s digging sometime between 1861 and 1869. But my guess is that it happened in very late 1864 or in 1865.

No clear account is left stating exactly where Pike dug. There are many vague descriptions of his “ditch”, for example a November 1909 Seattle Times editorial. It described Pike’s work as “a six foot ditch, evidently to show that a ship canal could be constructed.” That article seems to draw from the account written by Army Corps engineer Clapp in 1903, which stated that Pike dug a “six-foot-wide, shallow ditch.”

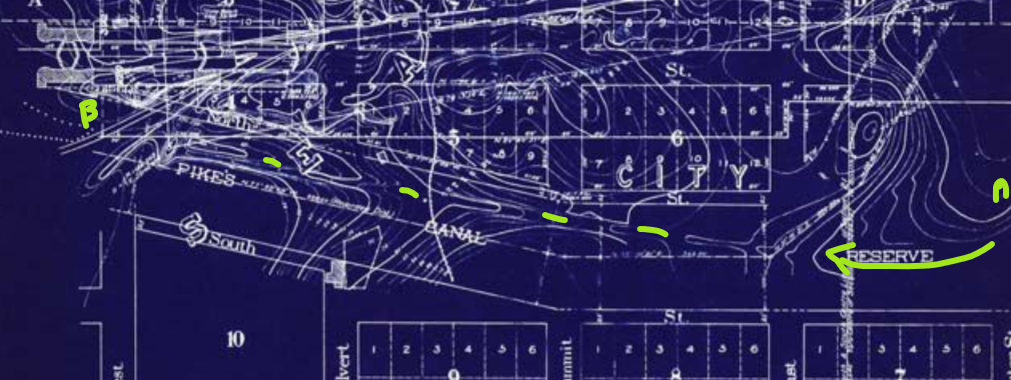

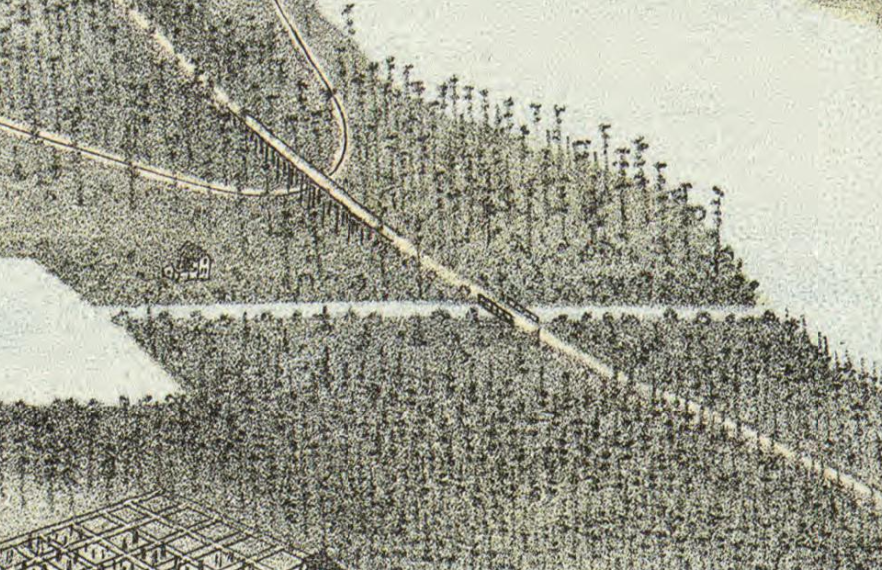

Surprisingly, as late as 1905 contours were visible on a topographic map that must have included Pike’s work. They may have also included a coal railroad, which became the next crossing of Montlake.

Images of the portage under Pike

1870-1878: Coal rails

Visible in a detailed 1905 topographic map, a long, straight line angled through the portage, a bit south of the southern of the two Duwamish trails. It was clearly man-made.

There are two possible explanations for the line. Maybe it was simply the result of Harvey Pike’s digging. But, more likely, it was the visible remains of a short coal rail line that cut through the portage in August 1870.

The cross-lake route

The coal arrived via the Seattle Coal & Transportation Company from a mine in Newcastle to the Seattle waterfront. First it reached the portage by barge from the other side of Lake Washington. Next, the tram cars of coal were unloaded onto rails and pulled across the portage.

Contemporary articles described the cars as mostly pulled by gravity down to Lake Union. For nudges and the return trip, mules or horses pulled them for the first four years. A small steam engine took over from them in 1875. Continuing on their journey at Portage Bay, a scow took the cars to the southern tip of Lake Union. At last, the cars again took rails from Lake Union to Seattle’s harbor on Elliott Bay.

Digging for the railbed started in August 1870 and rail laying finished in March 1871.

SC&TC completed additional track improvements across the portage in 1874 and 1875, upgrading rails and driving piles for new docks. With new engines for the other sections of the route, the small locomotive The Ant was moved to the short portage railway in July 1875. SC&TC thereby improved efficiency of hauling coal from Newcastle to Seattle.

But the rails and engine were only in use for a few years. In 1878, the SC&TC abandoned the barges and tracks, routing coal over the new all-land Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad connection between the Newcastle coal mine to Seattle through Renton.

Finding the tracks

The Newcastle Historical Society recently released an update to the book The Coals of Newcastle, based on an extensive canvasing of archival material and re-understanding of the early history of coal in King County. Two map sources that they uncovered show rough possible locations of the line.

However, combined with the obviously incorrect canal depictions in later maps, these don’t seem clear enough guides for the location of the line.

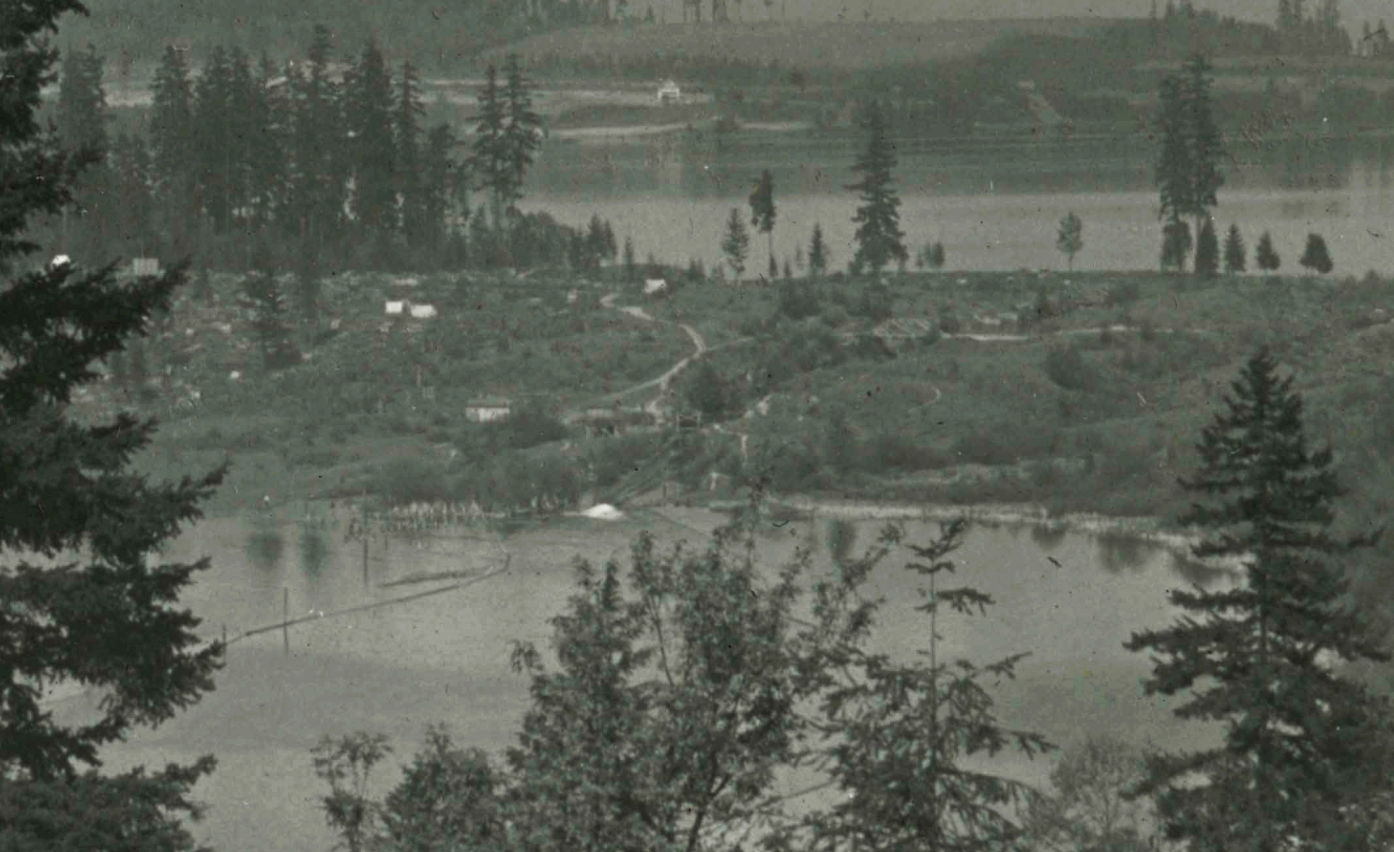

Pilings in Portage Bay and Union Bay seem to indicate the end points of the tracks and are consistent with the topographic map. One set of pilings is visible in all of the photos of the west end of the locks and flume that were later built in Portage Bay. Another was visible until at least 1909 in Union Bay to the east of a small bay that is now dirt and called the 520 Fill. These were at either end of the line in the 1905 map.

There is a stronger argument that the line on the 1905 topographic map was actually the coal line. In 1968, John Finger wrote a thesis for a doctorate in history at the UW, “Henry L. Yesler’s Seattle years 1852-1892“. It it he described Pike’s agreement in 1870 with Yesler et al’s Seattle Transportation Company, later the Seattle Coal & Transportation Company. Pike would lease land for a coal train tracks across the Canal Reserve. The straight line on the 1905 map was entirely within the Canal Reserve.

Where did the rail go?

The tracks were presumably pulled up in 1878 or soon after. Not only were the rails unused, they were also valuable. In a March 3, 1878 article, threats were leveled against thieves who stole “planks and iron” from the portage wharf. Those rails were valuable and could be reused.

With the rails gone, it seems that it would be used for portages instead of the old trail. Or maybe portages switched to the railbed in 1871, as soon as it was completed.

At least part of the rail bed continued being used for quite a long time. Later maps and photos, as late as 1900, include a footpath to Portage Bay that seems to be part of the old rail bed.

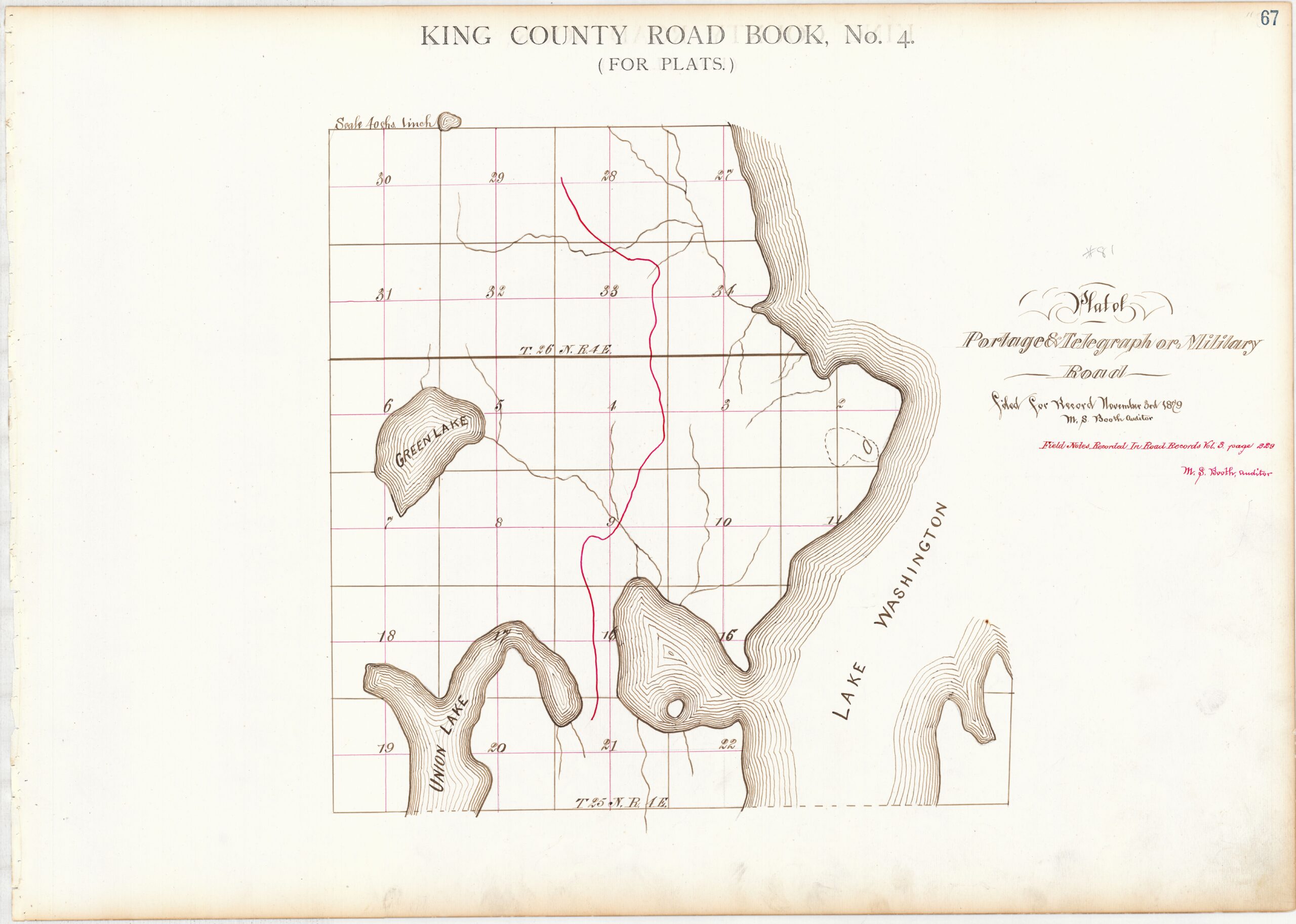

1879-1909: Portage Road

In April 1879, Robert Weedin successfully petitioned the King County commissioners to create a new road connecting the portage with the military road that came around the north side of Green Lake from the west and then headed north. His road would head to the east first, though, through the area that is currently Wedgwood and then Pinehurst.

The field notes of of Weedin’s Portage Road, written in August and filed in November, described the road’s start on the portage: “I commence at the terminating point of the Lake Union East Side Road… also on the Portage directly north of the old Rail Road track”.

Much later this road was known as the Snohomish Road, and was part of County Road Number 81. As Valarie Bunn recently wrote, Weedin had a land claim at Green lake and his brother had land at Wedgwood, so a road to the north directly benefited him.

David Denny petitioned the commissioners two months after Weedin to create a road from his house, through the land he owned that later became the Denny-Fuhrman Addition in Eastlake, and over the hill to Portage Bay and around to the portage. This was named the Road to Portage Road in his initial filing.

Later additions to the Portage Road stretched it directly south, eventually linking with 16th and Madison.

It’s worth mentioning that the survey notes for the Portage Road in 1879 said that it started “north of the old rail road”. However, that is not helpful for locating the coal train. The maps for Denny’s road and the Portage Road show the roads intersecting just east of center of the NW quarter section of section 21 of township 25N range 4E. This is currently on the entrance to the bike-ped 520 Trail across the bridge. That is north of the straight line on the topographic map, north of the portage ditch (described below), and north of the southern of the two native trails. So it does not confirm any routing.

Images of Portage Road

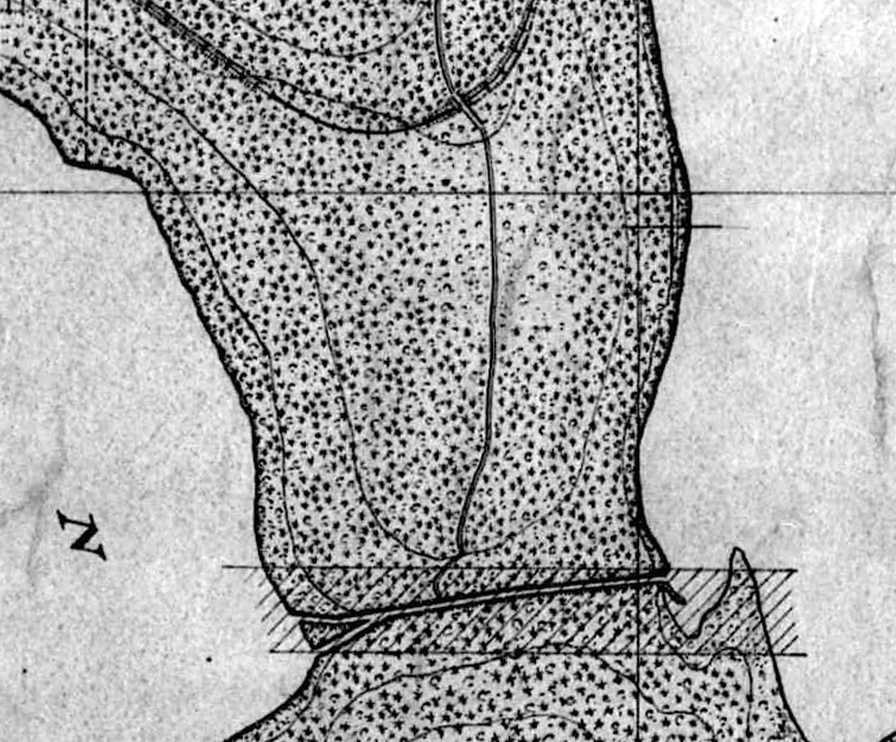

1885-1962: The Portage or Montlake ditch

In 1883, the Washington Improvement Company formed to turn the portage into a canal. Directed by leading citizens including David Denny (who purchased the Western Mill Company on Lake Union in 1882), Bagley, and Burke, the company intended to lower water levels in order to make more land available for farming and settlement, and to stop floods on the Black and Duwamish rivers.

WIC hired a crew of laborers to deliver on John Pike’s idea, aiming to dig a 16 foot wide canal 12 feet below the level of Lake Washington. After some initial work in 1884, efforts resumed in 1886. The final result was scaled back though, perhaps due to financial issues that they encountered.

Finishing in 1887, they dug a log chute or flume, or log raceway, that was able to carry logs down the seven or so vertical feet across the 300 yards through a gap cut in the isthmus. This is now referred to as the Montlake ditch, but at the time it was just the portage ditch — the name Montlake didn’t appear until 1908.

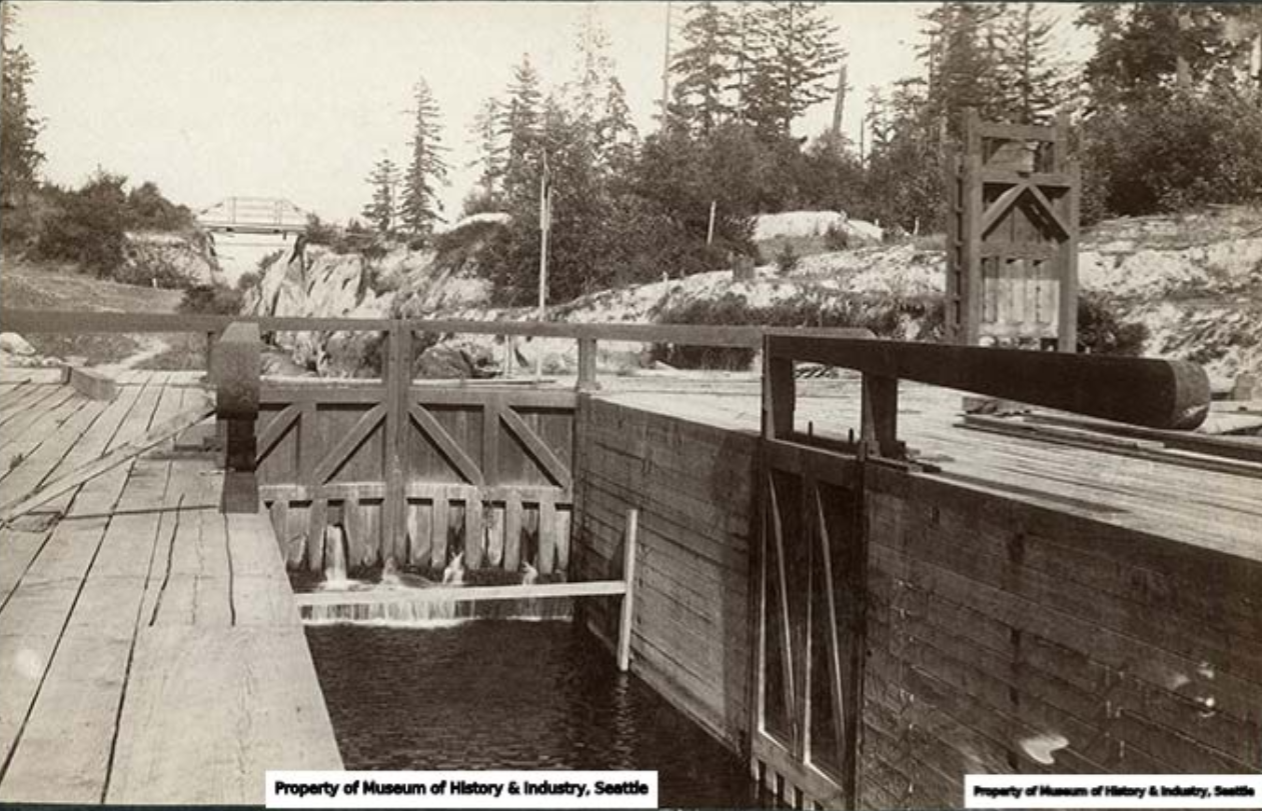

Anatomy of the ditch

The portage ditch ended on the Portage Bay side in a fork. To the north there was a small lock, but only the smallest of boats could get through the ditch. To the south a gate could be opened or closed, and on the other side a short aqueduct ended with a waterfall into the bay.

The effort wasn’t over for a larger canal, though. For example, an 1894 article proposed expansion of the ditch to solve severe flooding issues that continued in the river valleys that led to the Duwamish. Part of the proposal was that “the locks would be removed”.

“… and a small canal from Lake Washington through Lake Union and into Salmon bay. The latter is a small channel cut through the portage by the Washington Improvement Company for the purpose of floating logs into Lake Union and Salmon bay and running small steamers through.

September 16, 1894 Seattle P-I

Washington Improvement Company probably built its 1885 ditch on top of the old portage trail. Imagine why you would use the same trail for portage for centuries. It must have a shallow place to beach the canoe, and an easy rise on either end to carry it. No unnecessary hill would be crested and the shortest distance possible used between the beaches. The ditch’s general location and north/south angle were certainly a match for the old portage trail.

Images of the Portage ditch

1885-1909: Crossing the ditch

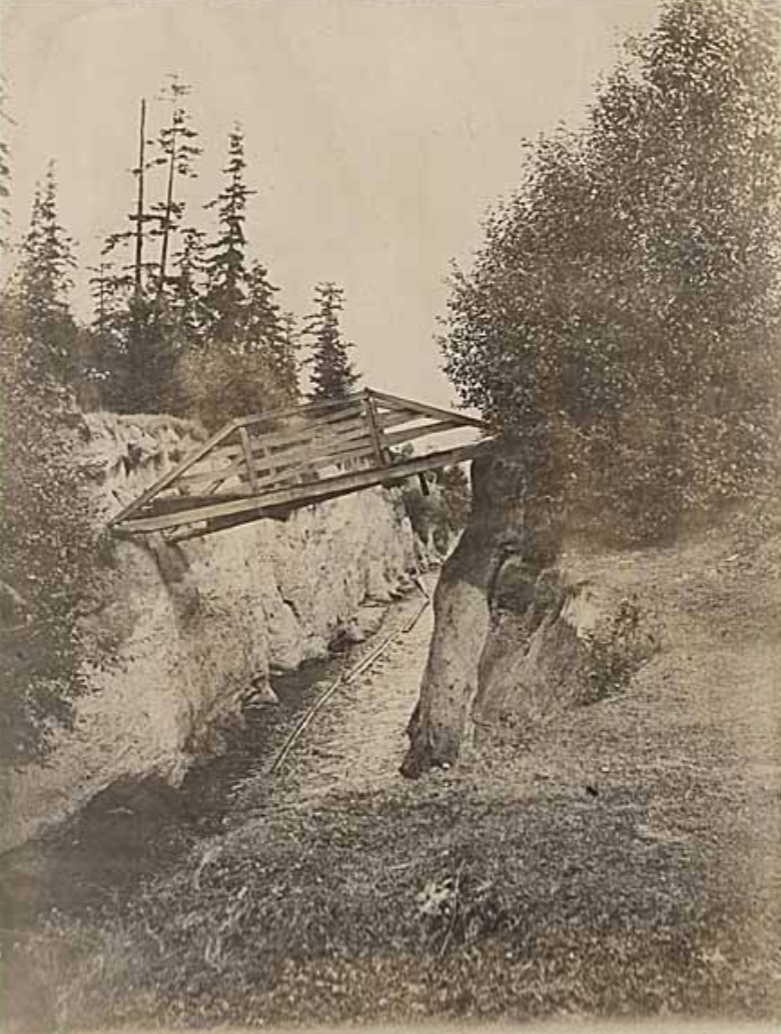

When WIC dug the canal from 1885 to 1887, the Portage Road needed a way to cross it. They laid a simple wood bridge across the ditch over a higher section in the middle, where twenty-foot cliffs dropped down to the water.

References to the bridge did not include a name. Probably the name was the Portage Bridge or Portage Road Bridge, but we could decide to refer to it as the Ditch Bridge (pronounced “britch”), or the Chutes Ladder.

After a decade of use, the the bridge was worn out. Indeed, in 1896 the Seattle Board of Public Works told Washington Improvement Company that its bridge was “so badly decayed as to be dangerous and unsafe for public travel.” That might have been when the north side of the bridge slid partway into the ditch after its footing eroded away, a scene visible in an undated photograph.

Ownership of the canal, locks, flume, and bridge switched from Washington Improvement Company to King County in March 1897. That was when King County condemned the entire portage including privately owned lots in Union City in order to transfer them to the United States government for a larger canal.

In 1898 King County contracted with John S. Brace, who operated the Western Mill in Lake Union. The contract made Brace the operator of the canal, letting him charge a fee to others who floated logs in the canal. In exchange he would allow the public use of the locks and pay for maintenance of the system. Presumably this included maintaining the bridge as well.

Images of the ditch bridge

1909-c1924: Montlake Boulevard bridge

It’s difficult to picture just how remote the portage remained in the early 1900s.

Until the Capitol Hill Additions began in 1901, there were only a few cabins north or east of Volunteer Park. In a 1909 aerial photo looking south at the hill, tents dotted the hillside in the Union City 2nd Addition.

The wagon road begun in 1879 was the only connection across the portage, even after Denny Hall (1895) and other buildings were constructed on the new university campus. So access to the university was by bicycle or streetcar to the west, across the Latona Bridge, where the University Bridge is today. The wagon road that stretched from 16th and Madison remained the only way north across the portage.

Montlake streetcar

Like the many failed attempts to build a true canal at the portage over the decades, it took several attempts in the early 1900s to build a road and streetcar from Madison to Montlake. Seattle Electric Company, the private monopoly streetcar operator, paid for the right to build north from Jefferson to Madison in 1902, but gave up even going that far and forfeit their franchise.

In 1905 the city proposed service on 23rd and 24th to the portage as part of a municipal streetcar system to serve gaps in SEC’s network. As part of their fight against the failed municipal system in 1905, SEC pledged to build a line on 23rd as far as about Aloha. While that didn’t happen immediately, SEC did work with the city in preparation for the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exhibition, Seattle’s first World’s Fair. So, real plans were discussed throughout 1907 and finally in November 1907 the plans were approved and franchise granted.

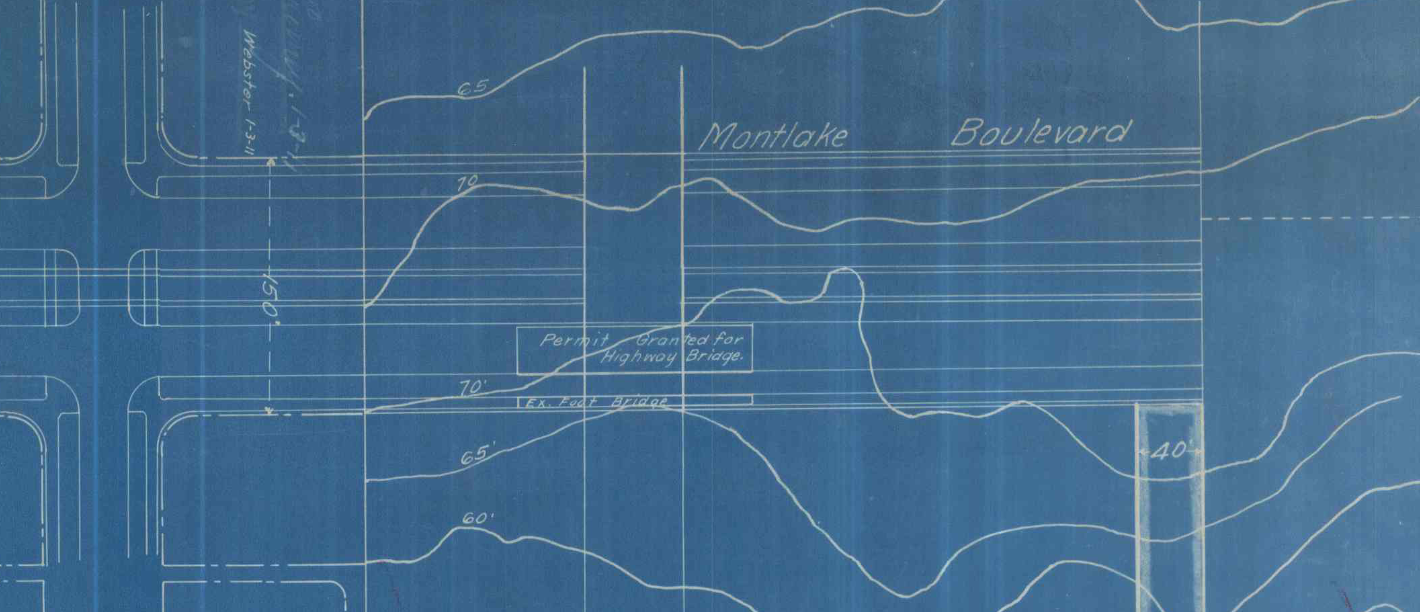

Finally, in early 1909 tracks reached the portage, with rail going in as the city built the road down the hill on 23rd, 24th, East Montlake Place, and then Montlake Boulevard, the latter a collaboration with the parks department. But the line was ready for opening day, serving a dedicated entrance at the southeast corner of the exposition grounds.

The old wagon road lay under the west edge of the boulevard, so its bridge was removed to make way for construction of the new boulevard’s bridge.

Montlake junction of Lake Washington Boulevard

Like with the road down 23rd, the parks board extended Lake Washington Boulevard north to a junction at the Montlake bridge. This looped along the shore of Lake Washington and Union Bay over a stretch described as the “university extension of Washington Park Boulevard”, and at least on one map called it the University Boulevard. The parks board employed a massive force to rush the road to completion. It opened on May 30, 1909, the day before the exposition.

As the exposition wound to a close, a new plat between the ditch and exposition ground was filed. The name was Montlake Park, after the new boulevard. Sales did not begin until 1914, though, as everyone prepared for the looming years of construction.

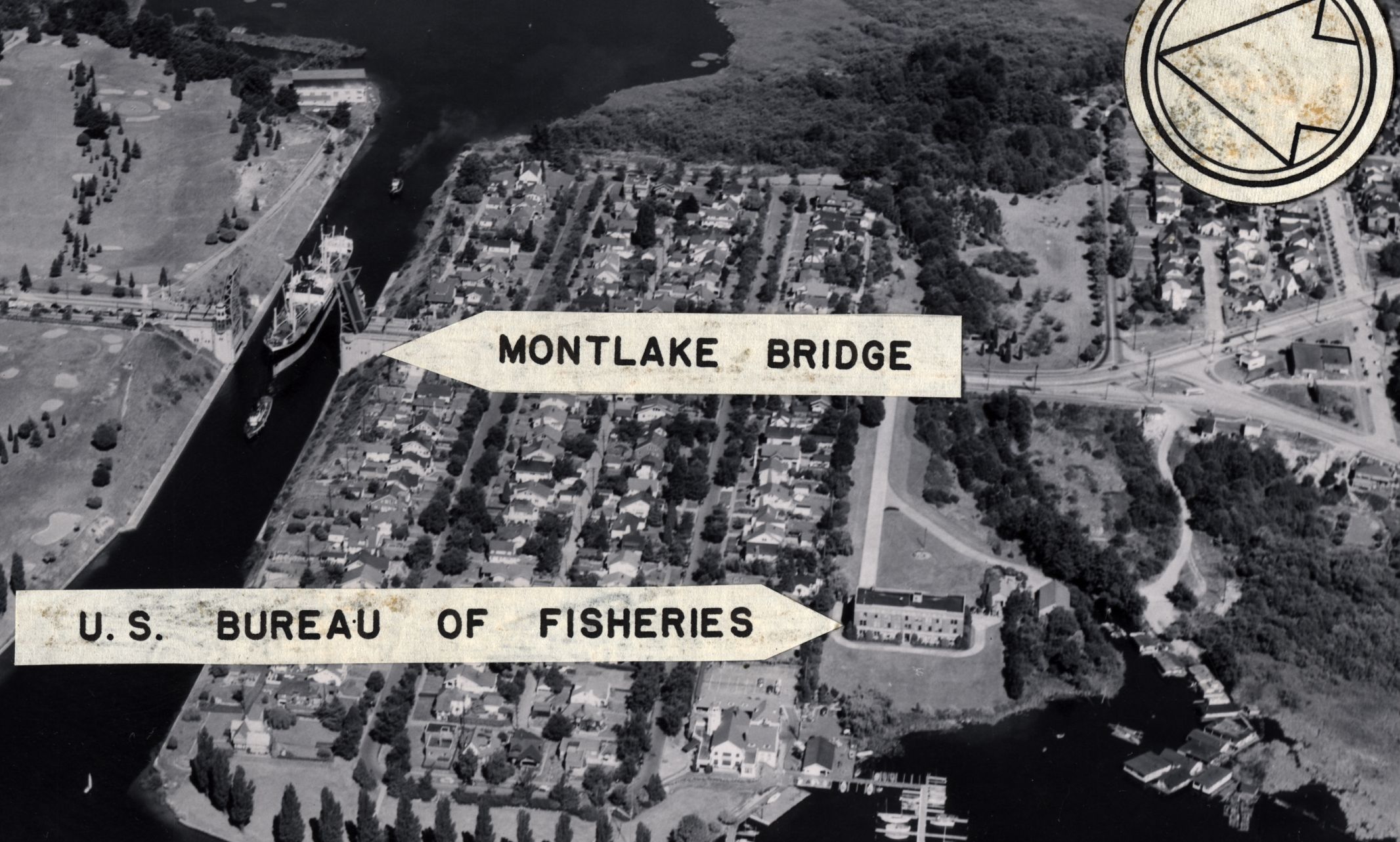

A fantastic photo, below, taken from a balloon ride at the exposition shows the new boulevard and Montlake Boulevard bridge.

A bridge is still included in street engineering diagrams from 1916, but the area under the bridge was visibly filled by 1929 aerial photographs. Perhaps construction for the Montlake Bridge in 1925 removed the temporary boulevard bridge.

Images of Montlake Boulevard

1910-1912: Footbridge over new canal

The AYPE World’s Fair ended on October 15, 1909. At the end of September, heavy machinery gathered on the portage, waiting to take action as soon as the fairgoers returned home.

Two weeks later, on October 27th, officials held the groundbreaking ceremony for a new canal across the portage. Two notable attendees were C. J. Erickson and John S. Brace. Erickson was the contractor for the canal work. Brace was the former manager of the ditch and Western Mill operator. He became the president of the Lake Washington Canal Company in 1907 and renewed efforts to create the canal.

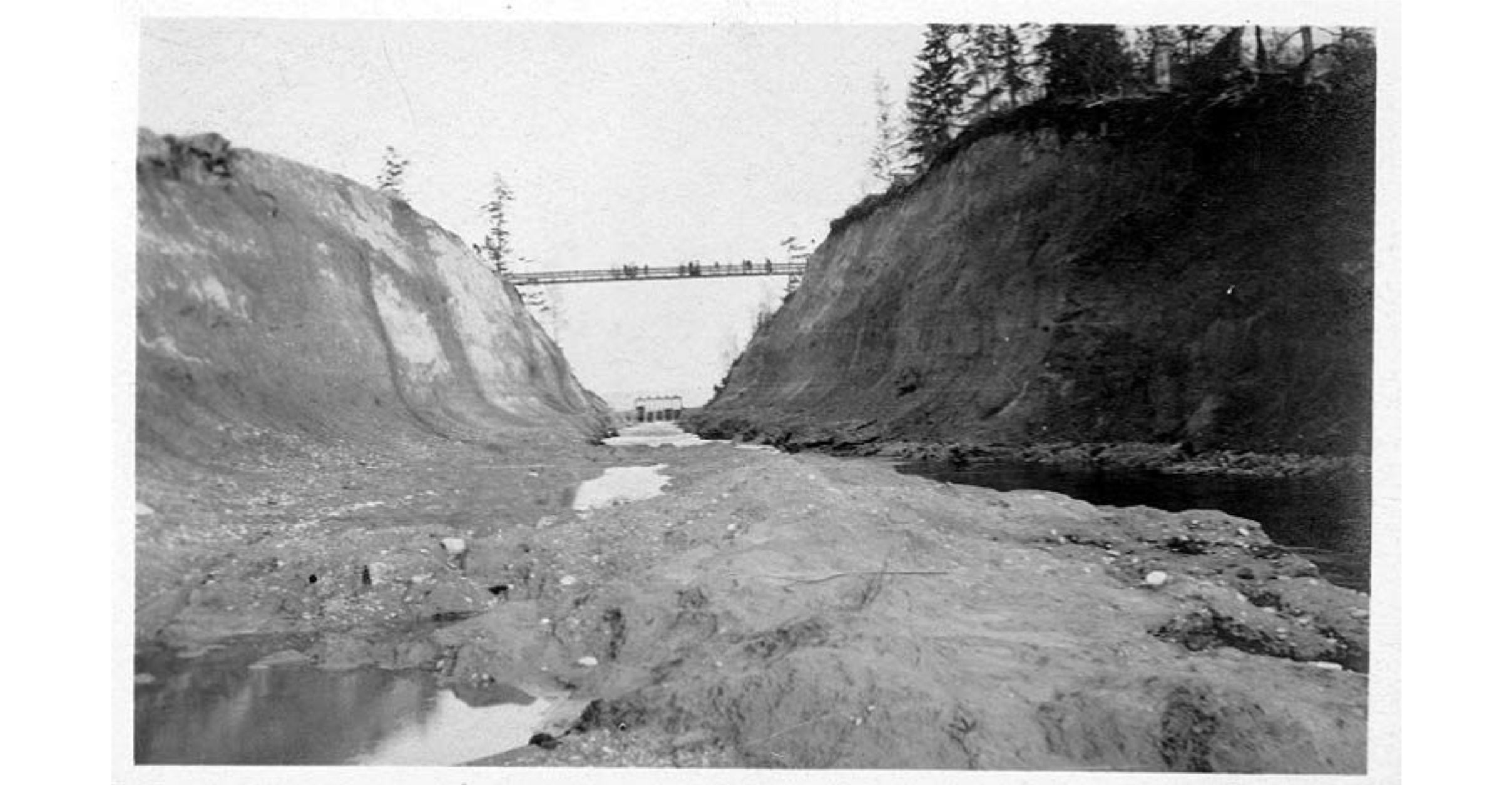

The common name for the new canal, the first stage of the Montlake Cut, was the Erickson canal. It was not navigable by boats, but only a gated spillway that could lower Lake Washington to its target height. Still, it was significantly larger than the ditch and a serious barrier to travel north and south.

Impacted citizens filed a petition in January 1910 for a footbridge over it. Seattle moved quickly. The city engineer filed plans in February, then signed a contract March for a bridge builder, and made payment for services in May. The contractor was Edwin E. Hall.

The city hoped to follow up with a horse, wagon, and automobile bridge in 1911. However, at the federal level the Corps of Engineers quickly denied the plan. Construction of the full Montlake Cut was looming, and there was no time for temporary measures.

Images of the canal’s suspension footbridge

1912-present: From portage canal to Montlake Cut

In 1912, crews deepened and widened the canal, removing the footbridge in May. The Montlake Cut opened to boats in 1916.

With the opening of the cut, Lake Washington dropped nine feet. One affect of that was to widen the isthmus, making it more difficult to visually match the landscape depicted on old maps or landmarks in old photos.

For many years, the only access to Montlake Park was from the south over the old portage ditch’s land, still held by the federal government. Of course, the UW’s boat house meant students could cross cut cut in their canoes and boats. And there was talk of a ferry that didn’t materialize. On occasion, particularly in the early 1920s, a pontoon bridge would link across the cut, blocking water traffic for an evening to allow foot access to a football game, fireworks, or other event.

After several attempts, Seattle citizens voted to put in the bascule bridge at Montlake that we have today, completed in 1925.

Images of the Montlake Cut

1962-present: Erasing the Montlake ditch

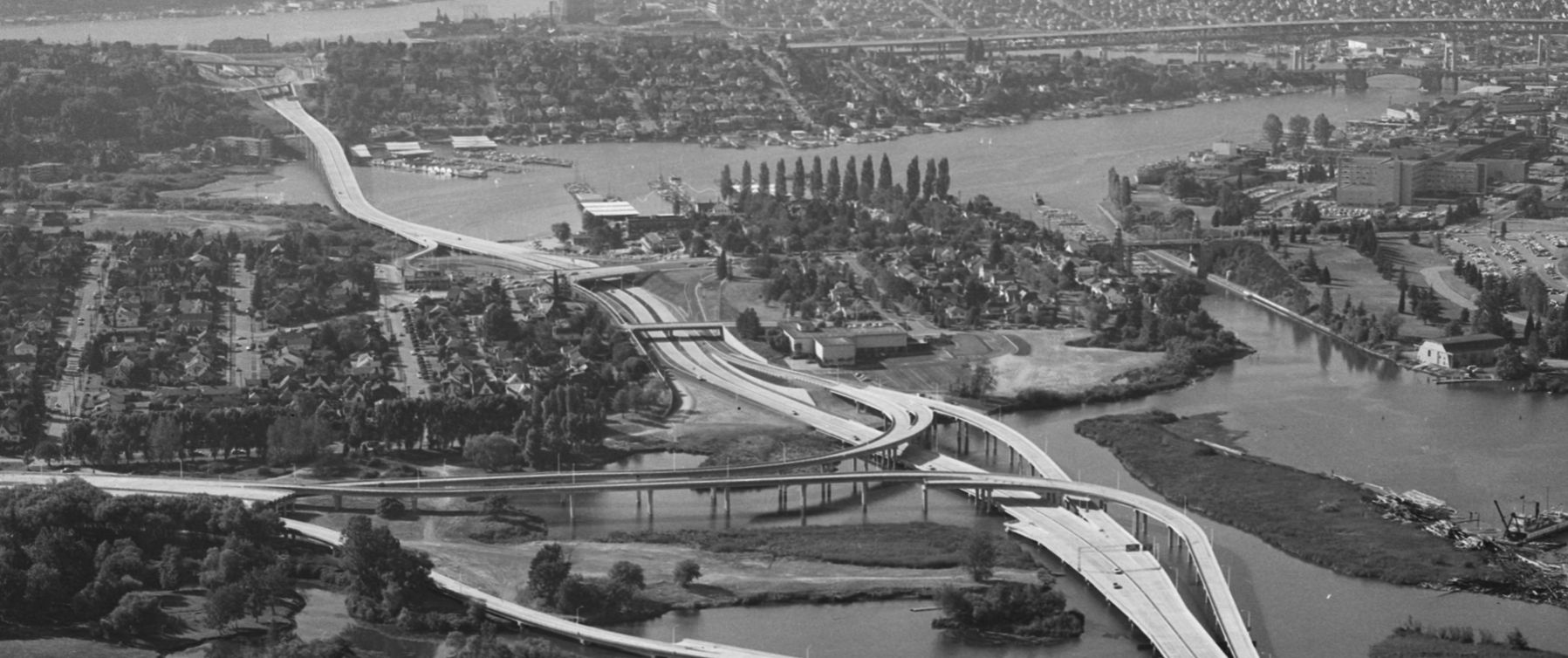

The federal government funded the interstate freeway system in 1956. Washington State and the City of Seattle promptly put together a plan for a network of freeways through the city. One important part of that was Primary Highway 1, quickly renamed State Route 520. It was built 1961 to 1963 across the portage. The highway arched over Portage Bay. It landed and dug into the portage, wiping out the remnants of the ditch. Then it floated off through Union Bay across Lake Washington.

Two new bridges were installed for city traffic, overpasses spanning SR-520. One carried Montlake Boulevard at about the spot of the 1909 Montlake Boulevard bridge. The other extended 24th Ave East north to the Museum of History & Industry.

Until SR520 construction, remnants of the ditch were clearly visible as a stretch of woods in aerial photographs. The pilings from the coal tram were already long gone, however. And the portage trails or wagon roads were distant memories.

Images of SR520 on the portage

Consolidated timeline

- Two portage trails east/west used by the Coast Salish people

- Bit of digging to try to improve the lakes’ connection by Harvey Pike in 1860s

- Coal tram tracks laid east/west across portage just south of southern portage trail in 1874, abandoned 1878

- Portage Road, a county wagon road, created north/south in 1879. Granted in April; map filed in November

- Ditch for transporting logs dug on about the site of southern old portage trail from, completed 1887, which included a bridge for the wagon road

- Boulevard bridge installed over ditch in spring 1909 along with Montlake Boulevard north/south over the portage replacing the wagon road

- Water spillway canal, “Erickson canal”, started October 1909 on site of current Montlake Cut

- Footbridge installed over new canal By Edwin E Hall in spring 1910, opening by May

- Footbridge removed in late spring 1912 to allow for completion of navigable canal

- Montlake Cut open for water traffic in 1916

- Pontoons used for special event access to UW from Montlake 1920s

- Montlake Bridge construction completed and opened to foot and vehicular traffic in June 1925

- SR-520 construction begins on Montlake, removing the portage ditch, in 1962

Closing the bridge

There are many other great sources that go into various facets of the portage in depth. But I must caution that there are many errors and omissions sprinkled across history, in particular of this place. Lorraine McConaghy, walking a loop of Lake Washington for her 60th birthday, put it this way:

The lakeshore is a manuscript on parchment so treasured, so rare, that it has been written over again and again… Some insight into the manuscript that had been overwritten. The lake and its shore is an enormous museum of sites, structures and stories, but the artifacts don’t speak for themselves, and the stories have fallen silent, not only muffled by the thunder of construction but the stilling of human voices through death and time.

Lorraine McConaghy “A history of Lake Washington, one step at a time”; and “Along Renton’s shore, pre-Boeing history has been erased” 2

The 1984 USGS publication Historical changes to Lake Washington and route of the Lake Washington Ship Canal is good overall. For the history and construction of the complete ship canal, see David Williams and Jennifer Ott’s book Waterway. Williams also has this overview on HistoryLink, and both have written more there. McConaghy highly recommended the out-of-print book Lake Washington Story by Lucile McDonald. Many other researchers have referenced it.

Finally, take an afternoon to dig through Paul Dorpat’s addendum to Jean Sherrard’s 2012 article “MOHAI’s Seattle Fire Mural”. He included many photos, descriptions, and thoughts that are all worth further inspection.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank a number of people for helping me reach a better understanding of Montlake’s history. The staff at King County Archives, Seattle Municipal Archives, and Seattle Public Utilities Engineering Vault. David Williams, Ron Edge, Valarie Bunn, Joe Mabel, Ben Lukoff, Matt McCauley, and indirectly Lorraine McConaghy and Paul Dorpat.

Please drop an email or leave a comment if you have a correction or question.

I expect to add to this article as I learn more. The article began with an attempt to understand whether it was possible to cross the portage on September 10, 1910. That was the day of the first hike by Boy Scouts in Seattle, from Ballard playfield to the Arboretum.

Further reading

Related articles that I wrote:

- Pike Street, University Boulevard, and other myths of Montlake – upcoming

- Seattle’s first Scout hike – upcoming

- Ice cream, beer, and the Montlake Drive-In Public Market (for CHS Blog)

- Renaming Seattle in 1906 – street names changes in Union City, later Montlake

- Roanoke Park and Seattle’s Broadway Steetcar

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One interesting thing about the old Canal Reserve is that it was the original location of the cherry trees that are now in the UW Quad. See https://magazine.washington.edu/feature/time-is-running-out-on-quads-signature-cherry-trees/ — I fear the couple of trees that weren’t moved to the UW were cut down during recent 520 construction, though.