Social media and web historians do a disservice to the memory of Seattle’s Shigeo and Chiseko Nagaishi. Photographs of racist vandalism that their family endured have become standard imagery for discussing the unlawful imprisonment of Japanese Americans during in the 1940s. But somehow Chiseko and Shigeo and their family are barely mentioned as people. And, discussion of their lives is nowhere to be found.

Let’s put those photographs back in context.

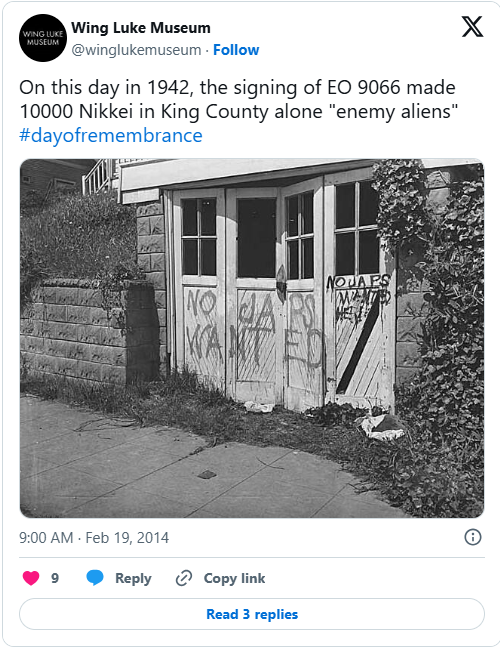

The Photograph

On May 10, 1945, husband and wife Shigeo and Chiseko brought their three children home to 1610 South Walker Street in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. It was the end of a three-year journey of unjustifiable imprisonment.

Their eldest daughter Haruko was now 6, half of her life spent behind barbed wire. Their two-year-old Kikue Minnie (born days after arrival at Minidoka, and her middle name taken from the camp) and one-year-old Amy Emiko lived their entire lives being punished as potential enemy agents of the United States of America.

The family was greeted by racist graffiti scrawled across their garage “No Japs Wanted” and a direct threat on their lives with “Death” and a skull and crossbones painted on the steps to their front door. The windows of their garage were bashed in, and the electrical wiring of their car cut up.

Shigeo, the father

Shigeo was born in Tacoma, Washington on June 15, 1900. In the Pierce County register his father’s name was left blank with only his profession, cook, filled in. He was the eldest of 12 children of father Matsujuro Nagaishi and mother Taku Yamaguchi. Shigeo’s place of birth is often mistakenly listed as Seattle.

The family did move to Seattle by 1906 where Matsujuro was eventually joined by his sons to work at his Oriental Fish Market. Shigeo’s relocation records list him as a “retail manager / fish / meat cutting”, reflecting his work with his father as well as later at his own store after his father died in 1936, Nisei Market.

The records also show that he only had an elementary school education from his time living in Japan, where he was sent to live with relatives.

Chiseko, the mother

Chiseko was better educated and a bit younger. Her relocation records show that she was born in Auburn on July 22, 1912. She completed high school there, growing up on a White River Valley farm with her parents Moritsuchi and Yoshi Murakami along with five brothers and four sisters.

Seattle’s Japantown merchants and South King County’s White River farmers were the two archetypes of Japanese American life before World War 2. Shigeo and Chiseko had both covered. If this were a novel, you’d dismiss the author for lack of originality. As a true story it’s pretty awesome.

The girls

I don’t believe Haruko ever married. Kikue and Amy did, though, and Shigeo had six grandchildren when he died in 1982.

I am providing a GEDCOM genealogy file for the family’s basic details, attached: Nagaishi-Family-Tree. However, I suspect that the family is very private and I have not attempted to develop the tree below the three daughters. I don’t see any interviews with them in Densho. No family memories are in the Nikkei Heritage Association’s Omoide series. Simple web searches don’t bring up anything.

I am very glad that they shared their plight with us in 1945 and that should be enough. I have to admit, though, that I’m curious to hear more.

The home

The photo with Haruko and Kikue and their parents in 1945 never has their names listed. So it’s no surprise that the location is not mentioned either.

The family had only lived at 1610 South Walker for just a couple of years before being sent to prison camps. Before that they lived close to their store on 7th and Main Street.

Staring at the graffiti, Shigeo and Chiseko told reporters that they would have to find a new home, unwelcome back in their neighborhood. I really want to know what happened next, after the photographers and journalists left.

Because the family did not leave. They spent more than six decades in that house. When Chiseko passed away in 2007 her three daughters sold their childhood home, ending a chapter of history.

Further reading:

Executive Order 9066, which led to the creation of prison camps for regular people like the Nagaishis.

Minidoka Irrigator, including an article about the Nagaishis.

Minidoka: An American Concentration Camp by Teresa Tamura for general context on the camp they lived in.

Here’s the Wing Luke Museum tweet and discussion that led to me writing this page [The opening sentence of my article was not intended as a criticism of Wing Luke. Individually I appreciate every time that the photos of the Nagaishi home are shared. As an aggregate, though, it’s disappointing that no text book author or social media publisher got curious enough to dig this story up before. We have amazing information at our fingertips now that previous historians did not. Be inspired!]:

Author’s note, April 2022: I recently noticed and corrected an odd and sexist phrasing in this article. I had written “so and so and his wife”, rather than presenting them as equals. Today I found another example of it. I’m very disappointed in myself, because I’m very aware of the slant that records and history have towards men, and especially white men. While proof reading the rest of the article afterwards, I suddenly realized that I used “internment” everywhere. This article dates from 2014, and clearly I had no problem with the term at that time. Later, I learned to favor clearer terms that everyone understands: Japanese Americans were imprisoned. I’ve left the article’s title as is for now but edited away other uses.

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this – I’d love to know what happened next, too.

Just this morning I was listening to the podcast of stories and jazz inspired by the Seattle area Japanese internment here http://kplu.org/post/panama-hotel-jazz-steve-griggs