A few significant Boy Scout expeditions shaped the self-identity of George Nakashima and his appreciation for trees and the natural world. These are those adventures.

Notice: Oden Annual 2 features my article “The high country trail food of George Nakashima”, focused on the food that Nakashima ate on the 1920 trek over the Olympics. The zine can be ordered for a limited time in 2022.

George Nakashima, woodworker

George Nakashima is remembered as a national treasure and as a leading innovator who embraced the natural beauty of wood in his furniture.

His studio in Pennsylvania is a national landmark. It is now run by his daughter Mira Nakashima, who continues to create handmade, one-of-a-kind treasures that celebrate individual pieces and cuts of wood.

The impact of Scouting on George Nakashima

While reflecting on his life in his autobiography, Soul of a Tree, George Nakashima looked back to his childhood to explain his early inspiration. He briefly described his time exploring the mountains around Seattle as his first memory of his connection with the outdoors, and of exploring the wilderness in search of himself.

Nakashima only shared a bit more in an oral history interview story about hiking over the Olympic Mountains. Even that has been overlooked by his biographers, so profiles of him repeat the simple fact in different ways: “As a child he was a member of the Boy Scouts;” “The future master woodworker was an Eagle Scout who fell in love with nature;” or “As an Eagle Scout, he spent a lot of time in the forests.”

The most provocative of these statements comes from his own woodworking gallery: “George Nakashima opened his woodworking business simply to earn a living using the skills he had learned as an Eagle Scout in the Pacific Northwest…”

Our teenage image of George Nakashima is based on our shared appreciation for Scouting, its values, and its embrace of adventure. But it lacks any specific facts or knowledge of his life.

Luckily his time in Scouting in Seattle lives on in the archived, printed word of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and Seattle Times. He was part of a few early, exciting events that hold, or deserve to hold, a place in local Scouting lore.

George Nakashima enters Scouting

He was was born on May 24, 1905. In his era there were no Cub Scouts, and boys entered troops starting at 12 years old. So George’s time in Boy Scouts was from about the fall of 1917 until he turned 18 in the spring of 1923 near the end of his senior year of high school.

Scouting came to America in early 1910, and was in Seattle by late summer. That put George in about the eighth group of new Scouts.

Rather than advancement, Seattle Scouting at the time was focused on outdoor activities and being helpful and brave. Newspapers chronicled their helpfulness raising money for Red Cross, selling war bonds, and other civic tasks. They also pushed themselves on long urban and mountain hikes. Although the Eagle Scout rank was first earned in New York in 1912, it took until 1920 for Seattle to award our first Eagle.

George was no different. His recorded rank advancement came in the summer of 1919, after one or two years in Boy Scouts. But despite possibly being an unranked Scout, in December 1918 he already set out on a snowshoeing adventure, the first known Nakashima activity. It was chronicled in the Seattle Times and even with a film shown in a downtown theater.

George Nakashima snowshoeing the Cascades

Nakashima’s first known Scout adventure took place during the school break between Christmas and New Years 1918.

This was the second published snowshoeing event for Seattle area Scouts. The previous was in January 1917, during a visit to the Mountaineers’ lodge at Rockport, just west of Snoqualmie Pass. But while that featured a series of day hikes, Nakashima’s 1918 trip started with four miles of snowshoeing over snowy terrain.

34 Boy Scouts and six leaders set out early on December 26th on a Northern Pacific passenger train from King Street Station, known as Union Station at the time, to the railroad service town of Martin just on the east side of Stampede Pass.

Their original plan was to take a Milwaukee Railroad passenger train which passed nearby their destination, but a washout earlier in the week closed that line temporarily. That required a change in plans, including a snowbound trek.

The Scouts were lucky to make the trip at all. A Scout event the prior week was canceled due to the influenza epidemic and because so many Scouts were sick.

The snowshoeing adventure

From Martin the Scouts set out on snowshoe for four miles to Lake Keechelus. A brief description of the hike in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer is reminiscent of Klondike Derby events that started four decades later. “Besides having a pair of snowshoes for each member in the party, they have been provided with two Alaska dog sleds that will be drawn by the scouts themselves and on which the provisions for their stay in the mountains will be carried.”

Their destination was the Mountain Goat Lodge of the College Club, located on the west side of Lake Keechelus at Roaring Creek. The cabin was “ideally located and amply arranged” according to the P-I, and “one of the best-equipped in the Northwest” per the Times. Cookware and mess kit awaited them, along with a mattress and cot.

Several articles in local papers reported on their adventure, which is why we know so much now. And at the Liberty Theater in downtown Seattle, a short film of their trip was shown. It’s unclear who in Scout leadership had access to a film camera in 1918, and unfortunately the film did not survive.

George Nakashima’s First Troop

On the trip with George were boys from many troops. Reviewing just ten of the 34 Scouts revealed five different troops: Troop 1 (at Broadway High), Troop 4, Troop 19, Troop 20, and George’s unit, Troop 35.

Troop 35 met at Lakeside Methodist Episcopal Church at the corner of 38th and Dakota in Columbia City. It was just a block from George’s family’s house at 38th and Genesee, possibly indicating he chose it through convenience and not church membership. However, in a 1985 oral history interview, George Nakashima mentioned that his parents Katsuharu and Susu did not hold firm religious convictions and instead were some-time members of Shinto, Buddhist, Methodist, or Baptist congregations.

At least four other boys from George’s troop attended. One was Ralph Northern, son of an engineer and teacher, who later went to work at the Mare Island Navy Shipyard. Another, George Bryant, was raised by a single mother a block from George, and later became a streetcar driver and bus driver.

Japanese American boys in Troop 35

There were also two other local Japanese American boys in his troop on the trip. Iwao Watanabe lived with his single mother and many siblings not far from the church and the Nakashimas. He went on to the UW with George and Elmer Katayama, and later lived in Chicago, first on work release from the Minidoka prison camp.

The other Japanese American boy was Rio Kashiwagi, whose extended family ran Seattle Tailors at Third and Main but lived within a couple blocks of the church, the Watanabes, and the Nakashimas. Rio later joined his family’s business, then moved with his wife and daughter to the densely Japanese American neighborhoods of South Los Angeles, specifically in Exposition Park, where they were neighbors with cartoonist Bob Kuwahara. The Kashiwagis returned to Los Angeles after their time in prison camps.

Scout leader’s son

One name stands out among the boys of the other units on the trip: R. B. Parsons. Reginald Bemis Parsons was the son of Reginald Howland Parsons, who was president of (Chief) Seattle Council. One of the council’s staffs’ tasks that winter was to secure a site for Seattle’s first remote summer camp. Of course they succeeded, and we now have Camp Parsons.

George Nakashima at Camp Parsons

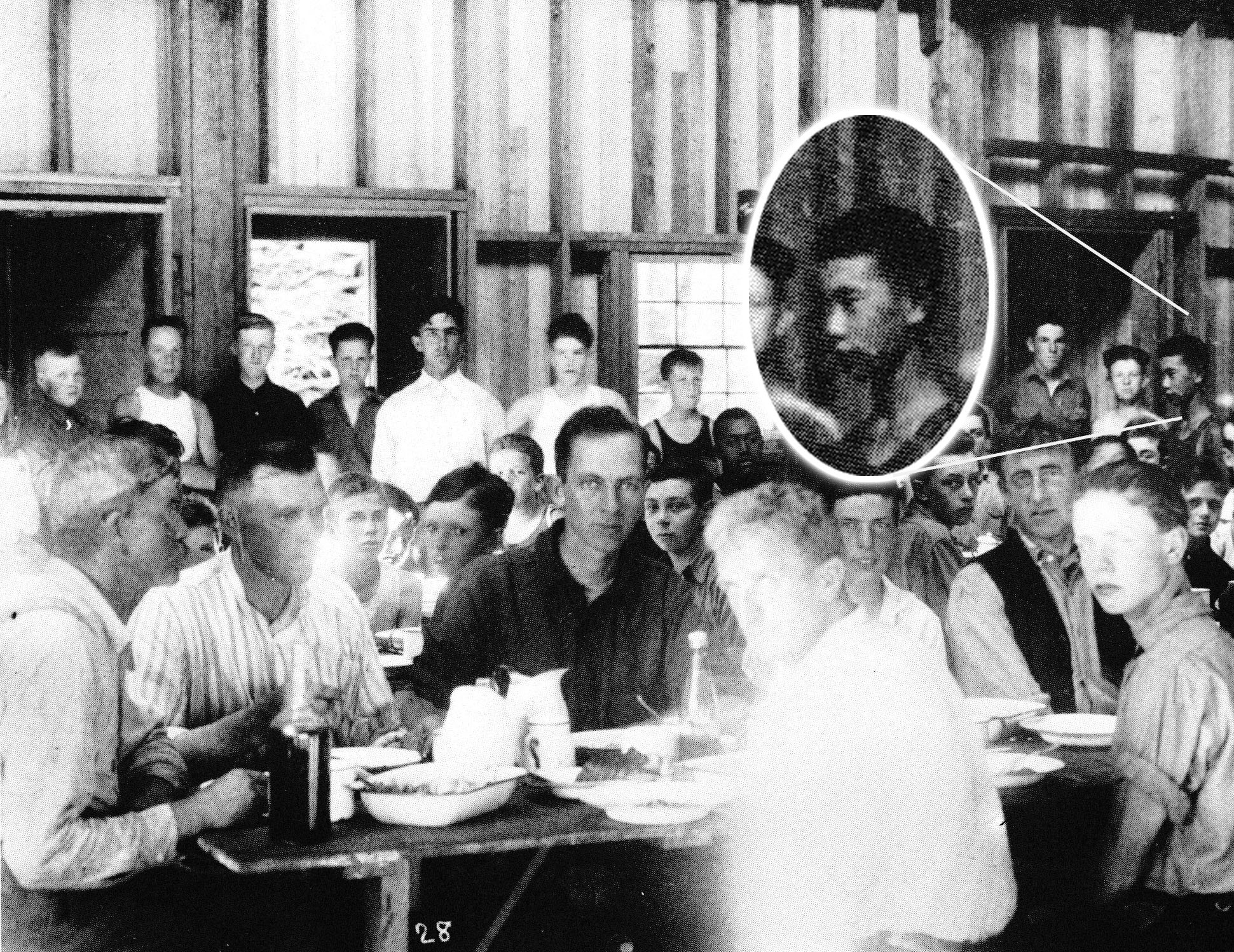

He attended the first summer of Camp Parsons in 1919. There, he met up with many of the Scouts who attended the snowshoeing event. The first year at Parsons was four weeks long, and Scouts could attend for as many weeks as they liked.

George apparently stayed for all four weeks of camp. Camp started on Monday, July 7th. By Sunday, July 27th he completed First Class. This entailed a fourteen mile hike, accurately guessing size, weight, and count of items, and identifying ten species of trees and plants. He may have also completed Tenderfoot and Second Class during the start of camp, because no other record remains of his advancement.

On the 27th he was photographed at the first meal in the mess hall, and in a campsite with Elmer Katayama’s family who visited from Seattle.

Camp ended after four weeks and officially closed on Tuesday, August 5th. After returning to Seattle, Nakashima used the swimming skills he built at Parsons in a city-wide athletic meet not far from his home at Mount Baker Park. Representing Columbia Playfield (now Rainier Playfield), he had the fastest time in the city for boys in a 50 yard swim on Lake Washington on August 7, 1919.

Becoming a “First Class and merit badge” Scout

In the Seattle PI’s July 27th article, Nakashima was not included in the lists of Scouts who earned merit badges or the camp emblem. However, by camp close on August 5th he earned the emblem and his first merit badges.

In 1919, merit badges could only be earned after First Class. So, the next achievement for him at Camp Parsons were merit badges: swimming, lifesaving, and craftsmanship.

The salt water of Jackson Cove in Hood Canal is still considered a difficult place for a young Scout to simply pass the swim test and play in the water. George Nakashima seemingly thrived in it. Exceeding simple qualification, he completed not only the Swimming merit badge but also Lifesaving.

Swimming required demonstrating proficiency at breast, crawl, and side strokes, as well as swimming 100 yards and 50 yards on the back.

Lifesaving required bringing a ten pound object from seven feet below the surface, carrying a heavier person twenty yards with two swimming forms, swimming fifty yards in clothes and shoes then undressing and returning to the shore, demonstrating an early form of CPR, and showing how to break a death grip, a practice that is no longer recommended or taught.

Building these skills and using the playtime pushed George to become the best open water swimmer in Seattle in 1919.

First experience as a wood craftsman?

Considering that Nakashima later became one of the world’s most famous wood craftsmen, it’s worth digging into what Craftsmanship merit badge entailed in 1919.

Craftsmanship merit badge went through tremendous change from 1915 to 1926. Here are the original requirements from the 1911 BSA Handbook:

To obtain a merit badge for Craftsmanship a scout must

Build and finish unassisted one of the following articles: a round, square or octagonal tabouret [stool]; round or square den or library table; hall or piano bench; rustic arm chair or swing to be hung with chains; or rustic table

He must also make plans or intelligent rough sketch drawing of the piece selected.

1911 BSA Handbook, Gutenberg

So, the original requirements all involved designing and building a piece of furniture, with unspecified materials.

In 1915, the requirements expanded to include eight very different options. A Scout could do work in metal, leather, basketry, pottery, cement, bookbinding, woodcarving, or wood. The requirements for “Craftwork in Wood” were almost word for word the same as the original Craftsmanship requirements.

This poses a very tantalizing possibility. George Nakashima’s first experience designing and crafting wood furniture may have been at Camp Parsons, during its first summer in 1919. Perhaps we can all agree to believe that it’s true?

Incidentally, BSA split Craftsmanship into eight different merit badges in 1926, allowing Scouts to complete more than one of the options. The original Craftsmanship merit badge became Woodcraft.

Headquarters troop

For a time, George Nakashima was a member of Chief Seattle Council’s headquarters troop. The headquarters troop assisted the council office in planning and carrying out events. They were also available to troops across the council for demonstrations and training in scoutcraft like signaling, first aid, fire making, and camping, as well as Scouting concepts. All members were First Class or above and members of another troop.

This was created after Harry Ellison moved from Rockford, Illinois and shared his own experience as a member of a headquarters troop there. Ellis became assistant Scoutmaster of Seattle’s HQ troop. The troop started on the Sunday of Thanksgiving weekend, November 30, 1919.

The troop was mostly First Class Scouts, including Nakashima and Aldus Hoopman. Seattle only had three scouts of higher rank: Loring Salinger, star scout; Frederick Held, Life Scout; and Wilden Baldwin, Eagle Scout. They were patrol leaders and senior patrol leader.

Easter Hike to Echo Lake by George Nakashima

At the start of 1920, the Seattle Council renumbered troops in north and south Seattle, separating three districts with 100s in the north and 200s in the south. George Nakashima’s troop was renumbered from 35 to 205.

Troop 205 went on a backpacking trip to Echo Lake, now known as Lake Desire, during Seattle schools’ Easter vacation. That stretched from Saturday March 27 to Sunday April 4, but their hike was Monday to Friday. Their trip was recounted by troop scribe Bernhardt Jacobsen. Although he provided many details, he did not give names, so we don’t know which of the characters was George.

The hike was six miles, but the Scouts only stayed together for one mile. Then six took off running to the start of the trail. There, three left on their own while others waited for the rest of the troop. The first three left the trail at some point and got lost in the woods. They finally made their way back to the start, arriving in camp two hours after the others.

With no shack to camp in, the Scouts all made their own shelter to sleep. Again, two Scouts split themselves from the rest. Scared or a perhaps just lonely, the two begged to join the others’ shelter in the middle of the night.

After climbing Echo Peak (then known as Echo Mountain) on Tuesday, their plans were hampered on Thursday when snow began to fall. This continued into Friday, totaling more than six inches. The troop hiked out in the snow, cutting their trip short.

George Nakashima visits Camp Parsons again for Olympics trek

In its second year, Camp Parsons only allowed Second Class and above Scouts. However it also opened to youth outside of Seattle. This drew in boys from around the region. Seattle Council’s new executive director, Stuart Walsh, relocated from Chicago, and a group of Scouts came from there to visit him and Camp Parsons in 1920.

George Nakashima was one of the first to sign up during early registration for summer camp. As a result, he earned a pre-camp ride around Puget Sound on the council’s new boat, the Rolling Hitch, purchased with a donation by R. H. Parsons. It was a 39 foot patrol boat with small gas engine and a sail.

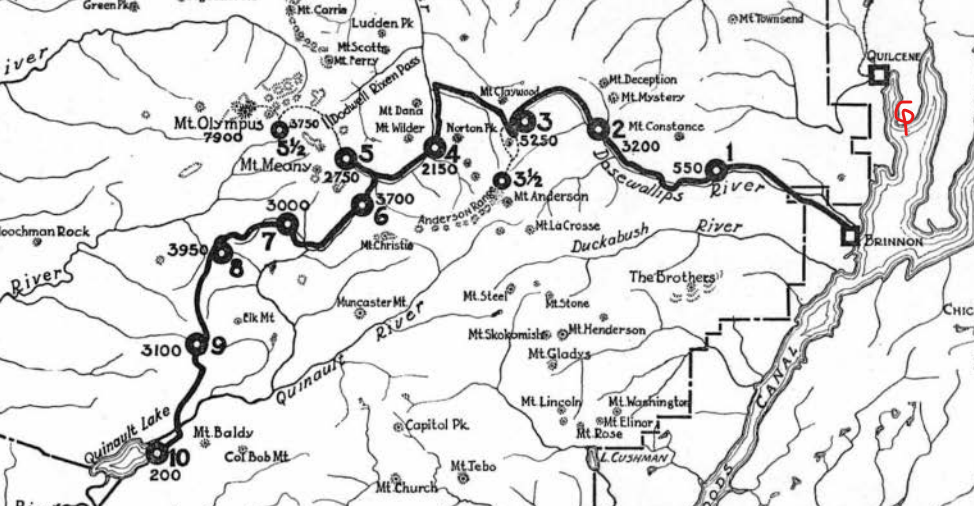

Parsons ran in 1920 for a period of twelve weeks, in two week blocks. George Nakashima registered for the fifth and sixth two-week sessions of Parsons, which should have meant from August 10th to September 5th. However, this really allowed him to participate in an adventurous hike that he remembered for decades.

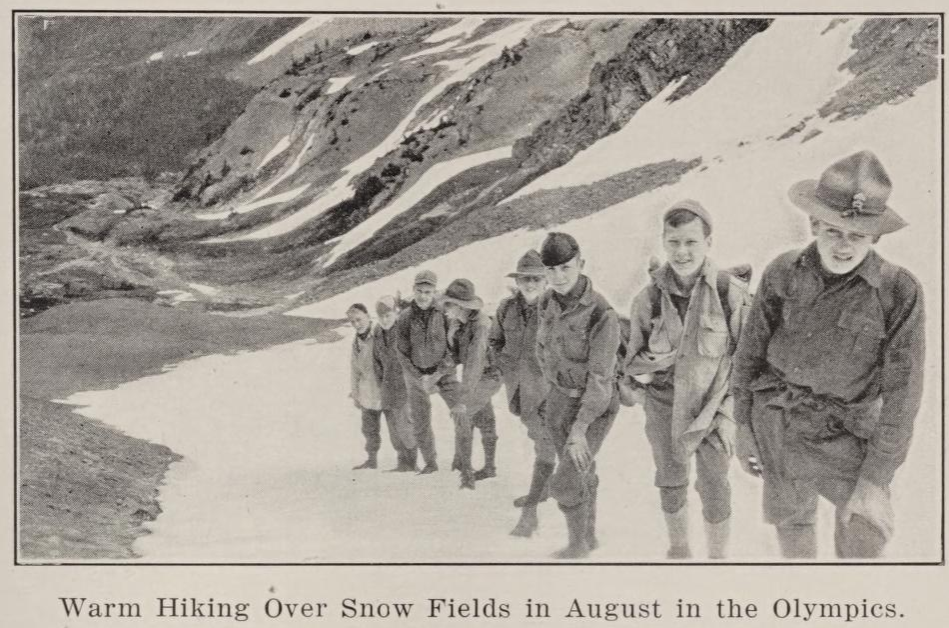

Hikes in the Olympics in 1920

The camp featured long hikes into the Olympics to Two Brothers, Mount Constance, and across the divide to the Pacific Ocean. It was the hike to the Pacific that drew Nakashima. In an oral history and his own writing, George referred to his time in Scouting by saying how much he loved hiking and being in the woods. Starting at age 12, he began carrying all of his supplies on his own shoulders for yearly, week-long trips. He loved roaming the mountains and hills and valleys. Fishing, and hunting sometimes. Crossing divides and looking over the other side. He loved what we would now call nature bathing, but he liked it as an extreme sport.

In particular, his oral history focused on the hike that he took over the Olympics from Hood Canal to the ocean. It was a backpacking trip from Camp Parsons that started on August 20, 1920.

Nakashima followed in the Mountaineers footsteps

George Nakashima’s backpacking trip headed on the same route that adults in the Mountaineers embarked on three weeks prior. But unlike the Mountaineers, who used a pack train to carry their supplies, the Boy Scouts carried everything on their own shoulders.

To understand the experience of the Scouts, we can look more closely at the group that blazed the trail over the Olympics for them. The Mountaineers are still an organization focused on encouraging and facilitating high country adventure. In the 1910s and 1920s they published an annual describing their activities, and through it we can understand the context of the Scouts.

Several years earlier, the 1917 Mountaineers annual strongly encouraged members to begin through-hiking. While most members focused on long trips with pack animal trains, or summiting peaks in fast or new ways, a group were drawn to the idea of taking all that was needed for multiple nights on your own shoulders. They would loop a long route, or travel between points reached by train, boat, or car.

The most significant problem for through-hiking was apparently planning lightweight but hearty meals. Indeed, the annual included precise lists of food to carry, 1 to 2 pounds per person per day.

Inception of the Sky Line Trail

However, many Mountaineers trips, including the one that preceded George over the Olympics, used donkey or horse trains to carry gear and supplies to forward spots on the trail.

80 Mountaineers set out across the Olympics at the end of July, arriving at the ocean after a leisurely trip of 21 days. Most of the Mountaineers 1920 trip covered pre-existing trails in the Olympics. But one section was brand new, the Sky Line Trail. The Mountaineers negotiated with the forest service for four years before it was finally created. It was so new that the Mountaineers had to delay their trip for several days, waiting for it to be completed.

On current National Parks Service maps, most of the Sky Line Trail is still labeled as “primitive”. A 1928 U. S. Forest Service trail inspection report described it as “Not for the careful or timid”, and it is still considered very challenging, as this recent backpacking report recounts.

The Mountaineers experience

The Mountaineers were delighted that it was the driest three week trip anyone could remember in the Olympics. It only rained on them one day.

Much of the 1920 annual’s description of the trip focuses on the first ascent of Mount Anderson. But there is a long section on their stay at Dosewallips basin from August 2nd to 8th. This captures some of the beauty that the Scouts saw soon after, and the views that deeply affected George Nakashima.

Quotes from Mountaineers 1920 Annual

The Dosewallips camp was voted by the party the most attractive of the outing. The river heads in one of those charming open parks such as one finds about Mount Rainier and in other parts of the Cascades, but which are of rarer occurrence in the heavily forested Olympics where rugged rocks, snow-pocketed, rise abruptly above the forests. On an upper terrace under the shadows of Hayden Pass camp was located. The whole place was bright with flowers, grassy stretches leading off to groves of alpine fir and hemlock. A barrier ridge headed by mount Sentinel, dropping to the saddle known as Haden Pass and continuing to the summit rocks of Mount Claywood cut off distant views but challenged all who would greet the snow peaks to come higher. The effort of a climb to this garden wall was well rewarded and few there were who let a day pass without a look over the edge.

From there the most immediate and commanding object was Mount Anderson, its broad flank glacier-clad, double summited, sharply cutting the sky with broken toothed edge. Far to the west, beyond a network of valleys and somber green hills, rose the vast bulk of Olympus, king of the group, and attending him, as if obeisant, Mounts Queets, Meany and Seattle. At times off in the southeast Rainier could be seen framed by a notch in the eastern Olympics.

Mountaineers Annual 1920, page 13

The Mountaineers trip day by day

| Date | Miles | Notes |

| Jul 31 | 5 | Logging trail from Brinnon to Elkhorn camp |

| Aug 1 | 12 | Upriver to Northeast Burn behind Mount Mystery |

| Aug 2 | 7 | To Dosewallips basin through forest and meadow. Camp for 5 days. |

| Aug 8 | 11 | Across Hayden Pass, along the Hayes trail, up Elwha to Letha Creek |

| Aug 9 | 9 | Elwha basin, making five river crossings. Camp for 4 days. |

| Aug 14 | 7 | Return on Elwha then up to Low Divide. Camp 1 day. |

| Aug 16 | 6 | Up Promise Creek from junction with North Folk Quinault on new trail |

| Aug 17 | 8 | Head of South Kimta Creek on new trail and met crew (Sky Line Trail) |

| Aug 18 | 13 | Three Lakes trail to near head of Round Lake trail |

| Aug 19 | 14 | To Lake Quinault. The next day across and to Taholah by canoe. |

McKanaugh, a lone through-hiker

Another hiker was out in the Olympics in 1920 before the Boy Scouts, and even before the Mountaineers.

Henrietta McKanaugh spent 16 days crossing the Olympics. She was a reporter for the Oregon Journal, and enjoyed long distance hiking. After hearing about the Forest Service’s new trail work, she decided to give it a try, alone, under the guise of travel writing. She set out on July 16 from Brinnon and reached Lake Quinault on August 2.

In the early days she had it easy, assisted often by Forest Service employees and trail workers. For example, she got a ride up the first 10 miles from Brinnon along the Dosewallips. And the next day a pack horse carried her backpack.

Here are some quotes from two articles that McKanaugh published in the Oregon Journal.

McKanaugh’s first impressions of the Olympics

The miles in the Olympics are about twice as long as anywhere else. The reason for this is that miles are measured on the level, while Olympic trails are all of the corkscrew order. Thus it takes about 10,000 linear feet to make a mile. Dosewallips Meadows was a paradise of wild flowers nad mountain streams, surrounded by snow capped mountains. Through it I started in the morning up over the divide, but [losing track of the trail] I waited and allowed the trail openers to go ahead and pave the way. We wound our way up over the divide and watched the horse and held the guns while the forest service men with shovels scooped out a path over the soft shale on the steep mountain side… It rained as we climbed over the divide and witnessed the panorama of the vast and jagged system of Olympic beset by storm clouds with rumbling thunder in the distance and flashes of twisted lightning darting from peak to peak… That night the horse became frightened at a bear or cougar and broke his tether and made for home, necessitating a return trip by the trail workers. I shouldered my pack and turned to the left…

Oregon Daily Journal, Aug 08, 1920, page 10.

Lone hiker McKanaugh on the Elwha River Trail

“Elwha basin is one of the most wildly beautiful spots in the entire country. Completely surrounded by mountains, from whose sides roaring waterfalls, fed by milky glaciers, plunged hundreds of feet into churning torrents, only to plunge again into series after series of mountain streams below, the basin nestled, one of the gems of the Olympic region. Into this basin the sun blazed during the day but early hid behind the mountain rim in the afternoon when the shill of the snow and ice fields descended. Here the trial ends. Here the vanguards of the Olympics themselves begin, and up the pass can be obtained a front door view of Mount Olympus in all her glory. Here were stationed John Tolen and Hymen Humes, building a trail to Snowfinger for the use of the Mountaineers. Only a portion of the trail was completed… Here was a trail in the making and the problems and the difficulties besetting a trail builder were demonstrated in the falling rocky slopes, the sharp grades, the rocks and tree roots to be blasted, the logs to be sawed.

Oregon Daily Journal, Aug 08, 1920, page 10.

McKanaugh hiking to Dodwell-Rickson pass

“On Sunday, accompanied by Tolen, I ascended to Dodwell-Rickson pass. It was a long pull over sonw and ice fields, with careful watching for concealed crevasses. As we rose higher and higher the mountains below us revealed themselves in all their glory, range after range of blue and white, and their sharp outlines forming a jagged skyline in the distance. We rounded a corner and came upon Mount Olympus, frigid in her glacial congealment, with a shivering green lake at her base. The the ridge on our left obstructed our view somewhat so we scaled the cliff, whose formation was steplike, walked over more snow fields, and stopped on the end of a huge rock where nothing but atmosphere lay between us and Olympus. We took pictures and then we looked, rapt in silent awe at the huge mass of glistening snow and glaciers, rock studded and carved in sharp outlines that reared itself against the blue of the sky. And though Olympus was a marvel in itself and was the center of attraction, jagged mountain peaks of slightly lesser distinction abounded on every side. It was a place of unreality – of dreams…

“The following morning I started for Quinault lake. Tolen insisted upon baking me a nice fresh “bannock” to take along… [Griffin] told me I would have an awful hill to climb to the Low Divide. Even so, I did. I climbed all afternoon and was ready and eager to camp when I reached the summit, and found a beautiful grassy meadow at the headwaters of the Quinault river with Mount Christie forming a picture in front.”

Oregon Daily Journal, Aug 08, 1920, page 10.

McKanaugh wanders near Quinault

She entered a section of the trail that was almost indistinguishable, with just a few stakes to indicate where to hike. Before long she lost track of it. She wandered through the wilderness, overcoming hardships and dangers including dangling over a cliff at one point. Eventually she stumbled on the trail again and slept in an abandoned trail camp, knowing she was close to her destination. But she was overdue at Lake Quinault, and a ranger was out looking for her. He found her at the camp and rousted her from her bed, taking her to the new and nearby Finley Fire Lookout. The next day she descended to Lake Quinault and then back to Portland.

Her accounts were published on August 8 and August 15, and it’s possible that the Boy Scouts read them before leaving Seattle or at Camp Parsons.

George Nakashima sets off into the Olympics

Those accounts of the trail from the Mountaineers and McKanaugh are very valuable, because no firsthand account remains from the Boy Scouts themselves. What we have is a few brief descriptions of their physical feat, and two descriptions by Scout executive Stuart P. Walsh of trips into the Olympics in general.

Henrietta McKanaugh was back in Oregon by the time the Scouts started. Just as they entered the trail, the Mountaineers left it at Lake Quinault and began preparing to board canoes. The Scouts still did their best to catch up with them by the coast. The Scouts went at such breakneck speed that the canoes were not ready for them yet when they arrived five days later at Lake Quinault.

The hike began in Camp Parsons itself. They hiked along the Olympic Highway, now US 101, to Brinnon. There they turned up the Dosewallips River Trail into the Olympic Mountains.

From the news accounts, we don’t know exactly where they stopped. But we know that the longest day was 25 miles and included the crest of Hayden Pass. And their total trip was 105 miles in length. The last day was described as a half day. Perplexingly, the Mountaineers reported less miles on the trail, indicating perhaps side trips by the Scouts or maybe a type error in the article.

A few hints at their stops come from accounts of an inexplicable September 1919 trip through the Olympics by Scout Lucius Matthewson and Scout leader H. B. Cunningham. Cunningham described the long, steep trail from Brinnon with heavy packs, “Those first two days were all work and no play — heavy packs, poor trail… about ten miles is a good day’s work.” Perhaps the first day for Nakashima’s expedition was 10 miles as well.

Crossing the Hayden Pass divide

Cunningham and Matthewson stayed at a “permanent camp” that they called Mountain Home. This seems to be the current Dosewallips Campground. That would be another 10 miles up the trail for the 1920 crew, and a likely camp after they read Cunningham’s account and talked to the 1919 travelers. If so, they may have also taken the same side trip to Lake Constance, which would explain most of a 10 mile discrepancy between the 105 miles they hiked and the 92 mile length of the trail. Indeed, leader Robert Drake led another group of Scouts in July to Mountain Home and explored the nearby area, so he knew the area already.

Wherever they started this day from, we know that when they crossed Hayden Pass, they covered 25 miles. This stretch was originally known as the Hayes River Trail but is now nearly universally referred to as the Hayden Pass Trail. The grueling day would continue onto the Elwha River Trail as well. Cunningham wrote of this stretch, “Of course coming down from the divide is another matter — then fifteen and even twenty miles are possible on a good trail.” 13 miles hiking up would be followed by 12 miles floating down the other side of the mountain. 25 miles from Mountain Home would land them at Leitha Creek on the Elwha River Trail. It’s where the Mountaineers stayed on their fourth night.

Nakashima on knife edge trails

Their fourth day would take them over the brand-new Sky Line Trail, which follows along the top of a sharp ridge. 17 miles would get them to the headwaters of South Kimta Creek near Kimta Peak, where the Mountaineers made their eighth camp.

Nakashima’s crew’s last day in the mountains, if this division is correct, would take them 17 miles again, past the new fire lookout at Finley Peak. They took a trail that no longer exists down from the peak, continuing along the ridge to the southwest. They would end their day in the Quinault River Valley, perhaps stopping as soon as they hit flat land or maybe continuing to fresh water. The Mountaineers described this, “First a knife-edge trail, then forest increasingly moss-festooned till floor of Quinault Valley was reached.”

Field executive Ware described their last day as a “half day’s hike”. The Mountaineers camped on the south shore of Lake Quinault, but the Scouts had no canoes waiting for them. They may have hiked further on, to the highway. It would be a 10 mile hike. The next day they took a stage to Hoquiam, and from their a train back to Seattle.

“They demonstrated that boys of thirteen or fourteen can, when necessary, travel twenty miles a day steadily and safely through very rough country [with] all their equipment on their backs.”

Nakashima’s Olympic trek day by day

| Date | Miles | Note | Possible Camp |

| Aug 20 | 10? | Start from Camp Parsons, then up the Dosewallips River Trail | About 4-5 miles up trail from Brinnon |

| Aug 21 | 10? | Continue up Dosewallips River Trail | “Mountain Home”, current Dosewallips Campground |

| Aug 22 | 25 | 25 miles in the day over Hayden Pass | Elwha Creek Trail at Leitha Creek. The fourth Mountaineers Camp. |

| Aug 23 | 17? | Sky Line Trail | Head of South Kimta Creek near Kimta Peak. The Mountaineers’ eighth Camp. |

| Aug 24 | 17? | After descending from Finley Peak in the Quinault River Valley | |

| Aug 24 | 10? | Half a day’s hike to Lake Quinault |

Scout hikers with George Nakashima

Each of the hikers in George Nakashima’s party carried all of their gear in a backpack of thirty pounds.

They carried tents of Tanalite, described as being “stronger than balloon silk but weigh the same”. Together with mosquito netting and blankets the sleep system weighed in at five pounds.

Another 15 pounds or so were committed to cookware and packaged food. They used nesting tin or aluminum pots, and each hiker had a spoon, cup, and small plate. The food was made of a small amount of canned meat and jam, a supply of heavy breads, some meatloaf for the first night, but mostly dried and powdered goods. These included fruits like dried apples, prunes, peaches, and raisins; and ingredients like cereal, rice, sugar, ground wheat biscuit, salt, spices, dehydrated soup, powdered milk, and lemon powder.

Morning meals were cereal with cocoa and stewed fruit. Lunches were quick snacks on the trail: a piece of chocolate, two wheat cookies, a cup of raisins, and plenty of water. When snow was nearby they would use malted milk drops to make milkshakes. Dinners were more elaborate with a few items like stewed meat and vegetables, soup, macaroni and cheese, rice pudding, bread and butter, nut cake, soup, and tea.

Reportedly, 16 Scouts signed up for the hike in by August 1st. By the mid-hike article on August 22nd, 11 Scouts were listed, with the number repeated on August 29th. But following the hike three names were missing, perhaps indicating only 8 made the trip: Norman Ansorge (284), Kenneth Fry (147) and Robert Renshaw (155) were not mentioned in the September 5th article.

Visitors from Chicago in the Olympics

Camp Parsons had a group of Scouts visiting from the Chicago area in 1920. They were drawn perhaps by Seattle’s new Scout executive Stuart Walsh who relocated from there earlier in the year, and by Seattle’s field executive Harold Ware, also from Chicago.

The Scouts were led by Robert J. Drake, Scoutmaster of Troop 8 in Urbana, Illinois. He was an Eagle Scout, apparently the first in Chicago. Following Parsons, in 1921 he became director of Camp Hatetokwitit (Hate to Quit It) near Urbana-Champaign, and also became Scout Executive for Arrowhead Council. Drake died tragically of scarlet fever in 1929, and a new camp was named after him in 1932. It is still open every summer, Prairieland Council BSA’s Camp Drake.

Roster of Nakashima’s 1920 Olympic Hike

| Name | Troop | Note |

| George Nakashima | 205 | World renowned woodworker |

| Vivian Klug | 156 | Seattle chess champion 1929-1930 |

| Edwin Simmer | 284 | Became a doctor in San Francisco |

| Bob Gourlay | 284 | Entered family lumber business |

| Aldus Hoopman | 260 | Seattle’s first Eagle Scout |

| Elliott Fulton | 552, Chicago, Illinois | Became salesman of textiles |

| Cullen Everett Paramalee | 8, Urbana, Illinois | Became air conditioning engineer |

| Robert S. Lamon | 506, Chicago, Illinois | Became Middle East archaeologist |

| Harold D. Ware | Field Executive | Young career camp director |

| Robert J Drake | SM, 8, Urbana, Illinois | Namesake of Camp Drake |

George Nakashima after the Olympic trek

Membership and advancement

From late 1921 into 1922, George Nakashima held the leadership role of patrol leader for Troop 205’s Bull Dog Patrol. His patrol joined a council-wide treasure hunt on December 28, 1921. It took place at the Washington Park Arboretum.

They first needed to navigate a set of directions with compass. Then they were given photographs of four unique trees, taken during the summer. They had to identify them in the park and find a hidden message behind them. At the time of the event the trees were covered in snow, making the task more difficult. George’s Bull Dogs were not the fastest at navigation, but with the tree identification their combined time of 1:18 was more than an hour faster than the next team.

While still a member of Troop 205 in 1922, George Nakashima earned camping, first aid, personal health, public health, and electricity merit badges.

George Nakashima in troops 263, 204

George joined Troop 263 for the start of the 1922-1923 school year. Troop 263 met in South Park, quite distant for him, at South Park Presbyterian Church. His tenure at 263 was no more than a few months, perhaps indicating an issue in Troop 205. He earned hiking merit badge with 263 in October 1922.

Interestingly, Victor Steinbrueck, later the architect who designed the Space Needle, started in Troop 263 the year after George left. Steinbrueck met lifelong friend Fred Bassetti in 263, and Fred became a UW trained architect as well. It seems significant that the three of them were in Troop 263 in such close timing.

George moved to Troop 204 by January 1923. Troop 204 met in the Rainier Valley, closer to home. Troop 204 met at Columbia Baptist Church at 36th Ave S and S Edmunds St, now Southside Commons. In January 1923 he earned carpentry merit badge with Troop 204. That was his last recorded advancement as a youth in Boy Scouts.

George Nakashima becomes an Assistant Scoutmaster and an Eagle Scout

After aging out of Scouting at 18, George continued as an Assistant Scoutmaster with Troop 204 in the Rainier Valley.

Troop 204 visited Camp Parsons during the fourth period in 1923, and presumably George Nakashima returned with them. Troop 205 was not mentioned in the list of troops attending camp, supporting the idea that they disbanded prior to George joining Troop 263.

George Nakashima completed enough merit badges and was awarded Eagle Scout on April 18, 1924 as a member of Troop 204. In this era, Eagle Scout could be earned by adult leaders as well, allowing them to acquire Scout skill proficiencies and be recognized for it.

Asked at the court of honor how becoming an Eagle Scout has impacted him, George Nakashima replied that study of merit badge subjects helped him decide his life work. At that point he was studying forestry at the University of Washington. After two years he switched his major to architecture. The junction of forestry and architecture defined his career, and he was led to them by Scouting.

Final hikes and life after

Over Thanksgiving Break in 1925, Troop 204 drove to Silver Peak near Snoqualmie Pass. They joined a day of snow sports and games. The next month, over Christmas Break they hiked to Echo Lake (Lake Desire) and Otter Lake (Spring Lake). George helped lead the troop in learning outdoor cooking and completing requirements for advancements. His younger brother Victor earned Life Scout that month.

After the UW, George Nakashima got a masters in architecture from MIT. After his career was interrupted by the Minidoka prison camp, George became one of the most famous designers of wood furniture in America. His home and workshop in Pennsylvania is now a national historic landmark. Christie’s auction house has a page devoted to George, which says that the last item made by him that they sold was a coffee table from 1978 for $149,000.

1985 George Nakashima interview

After decades of success, George Nakashima reflected on how Scouting was “a great part of my life”.

Transcription of interview by Richard Polsky, Part 1, starting at 12:50

Hiking the Olympics

Polsky: When you were a kid, you said in your book that you used to spend a lot of time walking in the woods and the fields and hiking. How else would you describe yourself as a kid…?

Nakashima: [Two minutes describing racism in Seattle and his involvement in sports as a mediocre athlete, then…] Scout activity was a great part of my life. I used to enjoy that. We used to take great hikes in the Northwest. At times hiking from, I don’t know if you know where Hood Canal is? A long arm of water that projects into Puget Sound. We used to hike from Hood Canal to the ocean, for instance. It was over a hundred miles.

P: How old were you when you did that?

N: I would say somewheres around, I think I started when I was 12, actually. And it went on until I was maybe about the limit of the Scout age which was 18.

P: Were you strong, physically strong?

N: Oh yeah. I was physically strong. I used to swim alot. In athletics. Hiked alot.

Interview by Richard Polsky, 1985

About family and activity

… P: But when you went to the Scouts that was with kids that were not your brothers? Were they other kids in the neighborhood?

N: Yeah, I think my brothers were perhaps in the same troop. At least one of them. At one time I became Assistant Scoutmaster. And I think our family was the only Orientals.

P: What did you particularly like about the Boy Scouts?

N: Well I very much enjoyed roaming the mountains and the hills and the valleys. Crossing divides, and looking over the other side. Fishing and hunting….

P: Was this a normal activity for kids from that neighborhood… I mean the hiking.

N: Yeah. That was a normal activity in the Northwest. A very healthy activity. We used to swim alot. And way before anybody used to ski, we used to ski, and ice skate… when I went to college I thought I should stay involved in natural things, so I studied forestry for two years. And then I decided that I should do something like art or art history, and I changed to architecture. I enjoyed forestry. I was quite a good student… Before I graduated I was given a prize to study in France from the University of Washington. [Credits the university for giving him the prize despite not being Caucasian, then returns to discussion of prejudice and racism in the 1930s.]

Interview by Richard Polsky, 1985

George Nakashima and Japanese Americans in early Seattle Boy Scouts

Japanese Americans in George Nakashima’s troops and events

Surprisingly, George Nakashima stated during that interview that he was the only Asian American boy in his troop until his brother joined. Although that may be true in some context, even the limited history published in newspapers contradicts his statement.

As mentioned at the start of the article, at least two other Japanese American boys were in his first troop, Troop 35, later numbered 205. His neighbors Rio Kashiwagi and Iwao Watanabe both joined him on the trip to the College Club’s snowy cabin near Snoqualmie Pass.

Likewise, his first visit to Camp Parsons included a Japanese American boy from another troop. That was Elmer Katayama of Troop 57.

Furthermore, when George entered Troop 263 briefly, he had Chester “Chet” Sakura to look up to. Although Sakura was three months younger, he was already an Eagle Scout. Overall, he was the 26th Eagle Scout in Seattle, but he was the first Asian American Eagle Scout here. Chet’s younger brother Howard “Chip” Sakura was also a member of the troop and working his way towards First Class.

Perhaps Nakashima’s memory was focused on the end of his Scouting career. It could be that George was the only Asian American in his last unit, Troop 204. No mention of another Asian American other than his brother Victor remains in local papers. And because he continued as an Assistant Scoutmaster, that group may have left the strongest impact in his mind. Or, he may have been thinking of something else, for example his trip over the Olympic Mountains.

All-Asian American troops in Seattle

Another factor to consider, though, is that by the mid-1920s, when George was a leader in Troop 204, there were already several troops in Seattle with entirely or almost entirely Japanese American or Chinese American boys. So, his memory may have been reshaped while considering the difference of his experience in the late 1910s as a minority in a troop, and comparing it with that of Japanese American boys in Seattle in the mid-1920s in segregated troops.

Troop 53 started at Japanese Baptist Church in 1920 and Troop 54 started at Chinese Baptist Church in 1922. Troop 53’s Scoutmaster in 1925, Clarence Arai, was a member of the University of Washington’s Japanese Club (later renamed SYNKOA) with George while George was ASM in Troop 204. In 1924, Troop 55 started at Japanese Methodist Church.

Additionally, there were several more units with entirely Japanese American boys that started after Nakashima graduated from the UW. Those included a troop at Bailey Gatzert Elementary sponsored by American Legion Post 1 (Troop 59 in 1928), Seattle Buddhist Church (1930, numbered Troop 52 when restarted in 1940), St. Peter’s Episcopal Church (Troop 51 in about 1935), and Maryknoll school (Troop 50 in about 1937, predominantly Japanese American with a growing Filipino American share).

Further Reading

Related articles by Rob Ketcherside.

Seattle Scouting:

- Elmer Katayama at Camp Parsons’ opening

- The Start of Scouting in Seattle

- Seattle’s first Scout hike

- Seattle’s first patrol leaders

- Seattle’s first Eagle Scout

- Troops 50 to 59

Seattle Cub Scouting:

- Cub Scouts began in Port Angeles (part 1)

- Camp DYB, 1925 Cub camp in Port Angeles (part 2)

- Wolf Cubs lost at war (part 3)

- Blue Ox Camp, Seattle’s Paul Bunyan themed camp (part 4)

- What did they sing at Blue Ox Camp? (part 5)

- Cub Scout Alphabet

Possible future articles which look at the start of Scouting in Seattle, and activity by Japanese American boys. Some are partially drafted. Those could include:

- The Scout patrol at Collins Park

- Capitol Hill’s first Scouts

Here are articles I’ve written about Japanese Americans and Japan:

- Life of Iconic Internment Family

- Pike/Pine’s non-white residents in 1910 and 1920

- Hiroshima playgrounds came from Seattle

- Arai Market in A shop on 11th (on CHS Blog)

- The Pink Dress on Boylston (on CHS Blog)

- Julia’s building past to present (on CHS Blog)

- Koba family and Halmar Apartments (on CHS Blog)

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.