Donald Trump’s grandfather

Yes, that Donald Trump. Get yourself an age appropriate beverage and a comfortable place to read this. I’d like the opportunity to correct some mistakes and some misconceptions in the tale of Donald Trump’s grandfather – Frederich Drumpf or Frederick Trump – and his time operating a restaurant in Seattle in the early 1890s. The unfortunately mistaken narrative came in Gwenda Blair’s 2000 book The Trumps, which was republished in 2015 with the unwieldy subtitle Three Generations of Builders and a Presidential Candidate. After that, a slew of articles about that book added to the errors in her work.

I abhor Donald Trump and his vision of a fearful, white America. But I love Seattle history, and I love finding stories woven from newly digitized information. No one else has chosen to provide counter narratives to Blair’s work, so let me do my part.

Update July 2016: I wrote a brief version of this article for Seattle news site Crosscut.com. Check that out first, then come back.

Update November 2017: I appeared in the British documentary Meet the Trumps in January. It is now on Netflix in the US.>

Frederick Trump, a starter bio

Frederick Trump (earlier, Frederich Drumpf) lived in Seattle from 1891 to 1893, and from 1897 to 1898. During his first stay he ran a restaurant named The Dairy in the seediest part of Seattle. At the time, Seattle was a business-first city where progressives and moralists struggled to clean up the place. They repeatedly tried and failed to rout out prostitution and gambling, and with each failure the effort continued anew. You could say it took until women’s suffrage in 1910 for things to change in our bureaucracy, or you could say it wasn’t until the 1970s that the police force got truly cleaned up, or you could look at the current DOJ driven reforms and say it’s still a work in progress.

In this article I focus on Frederick Trump’s first stay in Seattle. I trust Gwenda Blair for the rest of his biography, but at the same time hope that someone else is taking a critical eye to it. Blair says that prior to 1891 he lived in New York, where he arrived from Germany. From 1893 to 1897 he operated a hotel in the mining town of Monte Cristo, Washington. From 1898 to 1901 he operated a hotel in the gold rush town of Bennett, Yukon Territory. Then he started over, going back to Germany and New York again.

The direct sources on Frederich or Frederick or Fred Trump in Seattle are scarce. I’ll start off with a quick run through them. Some of these must have been Blair’s sources. She found a few more that I haven’t yet unearthed.

Frederick Trump in Seattle City Directories

The address for his restaurant appears repeatedly in city directories, and luckily we know where he lived. A bit later I take a long look at both locations.

The Seattle Polk directory for 1892 has a Fred Trump entry in the alphabetized section (available through the Washington State Digital Archives):

Trump Frederick, restaurant 208 Washington, res[idence] Pacific House

Also the same 1892 directory Restaurants heading in the business section lists Trump:

Trump Frederick 208 Washington

The 1892-1893 Corbett & Company Seattle directory for Trump, available through Ancestry.com, has Trump listed alphabetically:

Trump Fred, propr[ietor] Dairy Restaurant, 208 Washington

Same 1892-3 Corbett for Dairy on Ancestry has his restaurant listed by name:

DAIRY THE, Fred Trump, propr[ietor], 208 Washington

Same 1892-3 Corbett Restaurant listings on Ancestry include the Dairy:

DAIRY THE

F Trump, propr[ietor], 208 Washington

1893 Seattle Polk available through Ancestry.com has Trump listed alphabetically, although he had left town:

Trump Frederick, removed to Monte Cristo, Wash

Newspaper ads or articles with Trump or Dairy or 208 Washington

Trump ran an ad in the Seattle P-I looking for a partner January 24 to January 30, 1892:

WANTED – PARTNER IN ONE OF THE best paying restaurants in this city. Call on or address F. Trump, 208 Washington street.

The Dairy earned a mention in an August 7, 1892 Seattle P-I article when Trump’s waiter Charles Hurmann was arrested on a charge of arson.

Trump registered to vote and was listed in the November 25, 1892 Seattle Times.

Trump ran a classified ad from December 22, 1892 to January 5, 1893 for the sale of The Dairy:

FOR SALE – WELL PAYING RESTAURANT at an unusual bargain ; proprietor is going east. 208 Washington Street.

April 5, 1893 Seattle P-I lists Trump being reimbursed by the Board of Health for meals served to 30 people quarantined due to smallpox at the nearby Phoenix Hotel from December 29, 1892 to January 11, 1893.

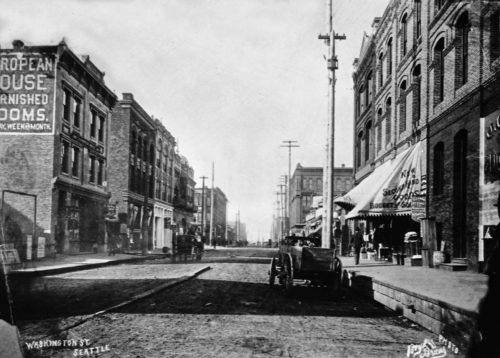

Where Frederick Trump lived and worked

Frederick trump lived at the northwest corner of Occidental and Washington, and his restaurant was in the building on the northeast corner. Although Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood is a city landmark district, and is also on the National Register of Historic Places, neither of these two buildings are well documented. For his residential hotel building, the story in books and databases is incorrect. Apparently no additional early research has been done since the 1970 landmark application to correct the errors. A worse fate befell the restaurant’s commercial building. It is almost completely forgotten because it was demolished before that application.

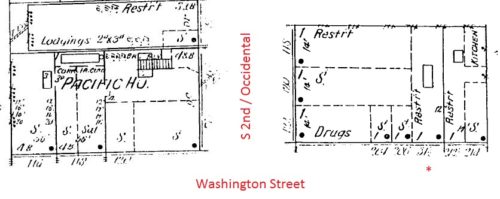

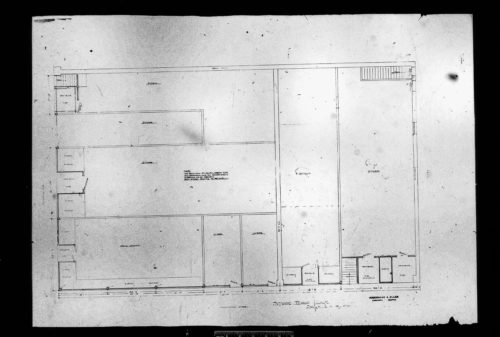

Here are both buildings on an 1893 Sanborn fire insurance map. On the left is the Pacific House, which had a basement, first floor commercial spaces, and lodgings on the 2nd through 4th floors. He lived in Pacific House, which is known today as the Interurban Hotel. On the right is an unnamed building which I’ll call the J. W. Hunt Building. It had retail in a single floor above ground, and a basement strangely missing from all maps.

Not the Chin Gee Hee Building

There’s so much to cover here. Let’s start by correcting misconceptions. On February 29, 2016, Seattle’s KIRO-TV news ran a segment about Fredrick Trump with bits of a brief interview with Gwenda Blair. They decided to broadcast from the location of his restaurant, and looked up 208 Washington in Google maps. It was a mistake that put them off by a block.

In 1889 a huge chunk of Seattle burned in what’s remembered as the Great Fire. Conversations immediately began about how to rebuild Seattle better than before. One needed change was rationalization of Seattle’s chaotic street names. New plats and areas added through annexation had silly names as well as different names for the same continuous road. North of Yesler there were Front, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Avenues. South of Yesler they were named Commercial, South 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Streets. There were other 2nd Avenues and 2nd Streets elsewhere in Seattle. The changes went into effect in 1895, and I’ve created an online lookup table and shared the data sheet as open data on figshare. 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Avenue South were shifted one street to the east to account for the angled connection at Yesler. The former South Second Street was renamed Occidental Avenue.

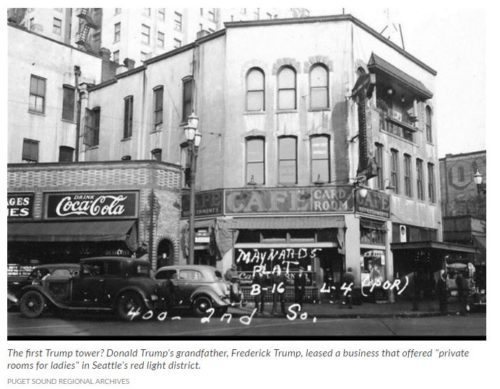

KIRO headed to the 200 block of Washington Street. That was the 300 block until 1895. So the building in KIRO’s broadcast, the building pictured above, was the Chin Gee Hee building. It’s perhaps the last remnant of Seattle’s original Chinatown.

(Off topic but incredibly fun facts… 1: The Chin Gee Hee building is shaped weird, right? In 1928, 2nd Avenue Extension was cut through to 4th Avenue South, destroying half of the block it’s on and requiring a corner of the building to be cut off. 2: The block above Yesler is the 500 block, and above that is 600, and so on. The block below Yesler is the South 100 block, then South 200, etc. Except for 2nd Avenue Extension South, which is numbered 400 block below Yesler and counts down to zero at its junction with 4th Avenue South.)

Error spreads

KIRO-TV’s mistake was picked up by Seattle NPR station KUOW on April 5, 2016 with a photo of the wrong building for his restaurant. Running with their error, they captioned the photo “The first Trump tower?” Seattle’s alt weekly The Stranger repackaged the mistake on April 11. On April 28 the North Kitsap Herald repeated the question as their title, and even compounded it by mistakenly stating that Frederick Trump owned Chin Gee Hee’s building. Recently a blog added further to the error, claiming that Frederick Trump advertised for prostitutes that lived over the restaurant.

Perhaps placing the restaurant in the Chin Gee Hee building resonated with earlier descriptions, like the July 28, 2015 Curbed article implying that there were opium dens and brothels in the same building as Trump.

Although Gwenda Blair has directly said in interviews that it is not correct to label Frederick Trump a pimp, she unfortunately didn’t say that in the book. Readers can be excused for coming away with that impression. It’s no surprise that there are widely shared blog posts calling him a pimp and even a drug dealer.

That is how myths are born.

The J. W. Hunt Building

Frederick Trump never rented space in Chin Gee Hee’s building. Instead, his restaurant was in the J. W. Hunt building a block away. Today it’s a parking lot at the northeast corner of Occidental and Washington. The Hunt building is completely missing from histories of Pioneer Square’s buildings because it was demolished in 1969, just before Pioneer Square was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. This is the first general chronicle of J. W. Hunt’s building, so I will tell all that I know.

Prior to the Great Fire, the block between South Second Street (Occidental), South Third Street (2nd Ave S), Mill Street (Yesler Way) and Washington was a maze of small wood frame buildings, built on piles over remnants of Seattle’s tideland saltwater marsh. In a narrow building facing South Second Street and stretching back into the block, John Winslow Hunt ran a blacksmith shop with wheelwright in back. Hunt came west from Maine to San Francisco for the gold rush in 1849 (he was a 49er) and moved to Seattle in 1870. He was a carriage maker until 1879, when illness caused him to reduce his business to blacksmithing and wheel repair done by a group of men under his employ.

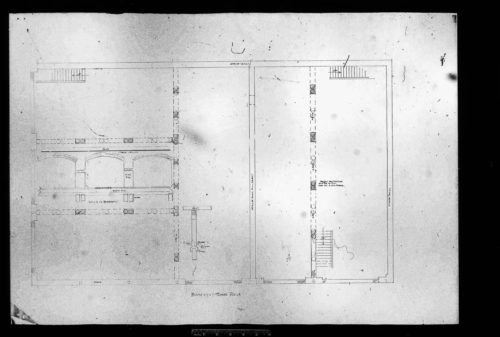

After the fire, Hunt redeveloped the land that his shop and neighboring structures had been on. He hired newcomer architect Samuel C. Woodall to design a one-story with basement brick building covering all of lot 4, block 9, Maynard’s Addition. Woodall is completely forgotten in Seattle history, and apparently was only here for a few years. His partner in 1890 was George Dornbach, who earned a short entry in the recent edition of the tome Shaping Seattle Architecture.

Descriptions in the Seattle P-I of the building under construction are confusing without context. In an August 1889 listing for the construction permit, the building plan was said to be two stories. In December the building was “up a story and a half”. Yet by June the next year, and until its demolition in 1969, it was described as one story with a basement.

The discrepancy is explained by David Williams in his recent book Too High & Too Steep:

Just as critical to enlarging the channels for business to flow was establishing a consistent grade for the new streets, which translated to raising them. Most of the Pioneer Square streets would be raised from their prefire elevation by an average of five feet per block.

In another passage Williams recounts visiting First Avenue South and Washington, a block from the Hunt building. “In fact, you are standing eleven feet higher than someone standing at the same intersection in 1875.” The street was raised many times. By Seattle Ordinance 383 in 1883 it was 15 feet, and a small raise in February 1889 moved it to 15.5 feet. After the fire streets were modified again, and the intersection of Occidental and Main was raised to 18.5 feet.

This all means that the basement was indeed below grade, but also was built on top of fill. Depending on your perspective it was two floors, or it was one floor with a basement hanging below street level.

An opportunity for merchants

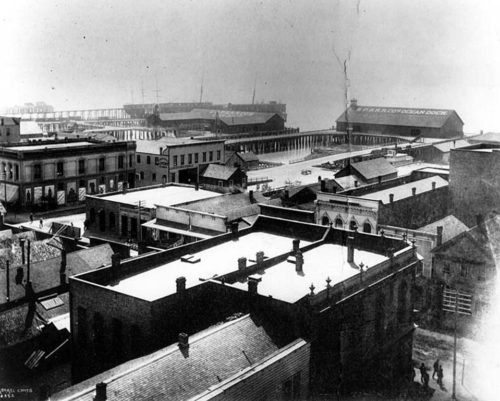

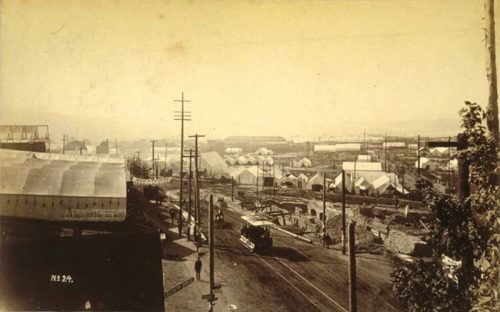

The reconstruction from 1889 to 1891 transformed a wasteland of charred rubble into several new, tall, brick neighborhoods of office buildings, factories, travel hotels, and residential hotels. A list of 1890 construction in the January 1, 1891 Seattle P-I (transcribed by my friend Curt and I and published as open data) included a hundred new buildings in the burnt area. Similar lists from December 1889 and June 1890, coupled with photos of the reconstruction, tell an amazing story of human enterprise. The workforce alone drew a staggering number of people to Seattle, and there was rich opportunity for those who served them. The population jumped by sixteen thousand people from February 1889 to May 1890, increasing from an official tally of 28,715 to 44,748. Because it happened during a boom when capital was flowing freely, the Great Fire was good for business.

As the 1893 map showed, the Hunt building included three restaurants, a druggist, and several other small storefronts. These other storefronts were apparently all pawnbrokers. In the 1892-3 Corbett directory they included Lurie Isaac at 214 Washington, Uncle Harris Loan Office (“oldest loan office in the city”) at 204 Washington, and Uncle Joe Loan office run by Joseph Hoeslech at 120 South Second. B. Elster at 218 Washington was perhaps in the building to the east.

Four other pawnbrokers were across the street, and the two of the remaining three pawnbrokers were a few blocks further. Over in the Polk directory, Simon Rumpf and Joseph Mayer were listed as the proprietors of Uncle Harris in 1892, and still there in 1893. (“Uncle” was a common term for pawnbroker, and the name Uncle Harris may have been taken from a prominent jeweler in San Francisco.) The Polk also included another jeweler in the large 214 Washington space, Nathan Phillips, listed separately.

And yes, you’re right, there really was a Rumpf two doors down from Drumpf.

Although Gwenda Blair included pawnbrokers in her list of tawdry businesses in the neighborhood, these were not simply predatory lenders. They were skilled jewelers – several of them paid to list in the Watchmaker and Jeweler section as well. Hoeslech’s son continued the jewelry trade, and is included in my profile of all of the street clocks that were ever near 4th and Pike. Mayer was really that Joseph Mayer, the one who became Seattle’s most important manufacturing jeweler and created hundreds of street clocks in addition to installing the E. Howard tower clocks in our region.

In 1892 Trump’s The Dairy Restaurant had Ripley & Ehle’s oyster restaurant on the west side and H. M. Tsukuno’s California Restaurant on the east side. Gwenda Blair refers to Bauman’s Second Hand Goods as neighboring The Dairy. Bauman’s store was addressed 212 1/2, which I believe was run out of space in the basement.

The drug store in the southwest corner storefront was Closson & Kelly, owned by John H. Closson and Charles Kelly. The business continued under different ownership until the 1960s.

Unresolved question of the Hunt basement

So what was downstairs in the basement? I’ll admit, I’m confused.

The 1890 directory included a lodging house run by Nels P. Peters, described in the vague words of the era as at the northeast corner of South Second Street and Washington. Was that the Hunt building, or did it actually refer to the Queen City Hotel next door? I am not sure. In 1891 the Queen City Trunk Company was listed as in the basement at the northeast corner of Occidental and Washington. But was it really in the basement of Queen City Hotel, hence the name? That seems more likely.

In 1892 Joseph Mayer was listed with “rooms” at 204 Washington, indicating he was living in the building. But the 204 Washington storefront was not large enough for a pawn shop, jewelers equipment, and a bed. The same thing seems true for Henry Bauman in 1892, who gave his residence and business as the same address. Was 212 1/2 downstairs? If the 1890 census were not lost in a fire, we could easily review a snapshot of all of the residents. Instead humanity waits to see how closely it can be replaced. We wait for more records to be scanned and available for full text search, and for it to be added to a mapped index.

More photos of the J. W. Hunt Building

Pacific House

Let’s rewind back to the landmark application. That application says that the building Frederick Trump lived in, the one at the northwest corner of Occidental and Washington, was first known as the Interurban Hotel. It lists the architect as unknown and the date of construction as 1906. With the aid of the digitized Seattle P-I, I can confidently say that origin story is false.

It actually dates from much earlier. It was known as the Pacific House from 1889 to 1901, Berkeley Hotel 1901 to 1906, and the Hotel Interurban from 1906. The 1949 earthquake caused the removal of the residential top three floors, leaving only the commercial floor and basement. The loss of floors ripped away the name Interurban as well. There have been many cafes, restaurants, taverns, and service businesses such as barbers and tailors over the years. The first Ivar’s restaurant was here in 1954. The remaining floor was the Last Supper Club from 2000 to 2015, and recently the bar Box House opened to replace it.

The building was developed in 1889 by George Kittinger and designed by architect Herman Steinmann. It was initially known as the Kittinger building or Kittinger block. This differentiated it from the adjoining Terry-Kittinger building which remains today, shortened from four floors to two. The Kittinger buliding was announced on March 10, 1889 in the Seattle P-I, three months before the Great Fire. With plans submitted and construction already underway, it had a head start on the rest of the neighborhood. Construction wrapped up in December 1889.

Architect Steinmann is remembered for designing the Terry-Kittinger building and a number of earlier buildings. However he left Seattle just after the fire, while there still was great demand for architects. Perhaps leveraging his work on the Bay View brewery, Steinman moved to New York City to continue designing breweries.

One fetid block

Gwenda Blair spent few words describing Pacific House and never gave it a name. She said, “Finally, when the Dairy closed, he staggered one fetid block through the rain to his flophouse, up the rude wooden staircase and down a narrow, unlit hall to his cold, shabby room.” Because none of us have discovered a first-hand account of the building by Trump or anyone else, I’m sure most of her description is simply an attempt to describe an abstracted 1890s residential hotel in a bad part of town. But Pacific House was only two years old when Trump moved in, not a run down tenement. Blair clearly knew this, describing the Great Fire quickly on page 41 and saying that the city was “brand new.” Perhaps she meant it was shabby in contrast with Trump’s final home in New York which she said was “much more elegant than anything the family had lived in before,” evidenced by a dumbwaiter and elevator. In that case shabby was a poor choice of words.

The single sentence on the Pacific House has one verifiable piece of information, which is wrong. The trip was not a “fetid block” from Trump’s restaurant. He had to walk past four businesses in the Hunt building, and cross a street, and he was home: not even close to a block away. Blair’s mistaken “block” might stem from the 1905 Baist fire insurance maps, or another source that included the Pacific Block. That was the original name of the building at the southeast corner of Yesler and Occidental that is now known as the Interurban Building. It was prominently written on maps.

This single fact, the walk from work to home, is draped with a highly judgmental adjective as well: “fetid”. What was the stench that Blair referred to? In David Williams’ Too High & Too Steep he says that early Seattle had an odor of rotting sawdust, similar to the aroma that Tacoma is famous for today. I’m sure Blair didn’t know this though since Williams’ book is so recent. Besides, I can’t imagine the stank still permeating in 1891 after the swamp remnants were filled after the fire. The other smell that comes to mind is horse manure, which plagued Victorian streets everywhere. Sure Washington Street’s businesses must have been active with cart deliveries, but Trump’s nose would have adjusted to this in New York at least, even if his hometown of Kallstadt was horse-free.

But it’s not just the fetid block. That one line of Blair’s about Pacific House is filled with entire chapters of error. It’s a vast error of omission, completely missing a gold mine of colorful history. Actually the error is not fairly ascribed to her. It’s our fault. Seattle historians have not told the story of the Pacific House, so how can we hold an outsider responsible for not telling it for us?

The story yet untold

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer mentioned the Pacific House often in the 1890s. Not for good reasons, though. If Frederick Trump’s restaurant was in this building, I would give more credence to the suggestion that he was involved in crime in Seattle in 1892.

Here’s a sample, from September 3, 1892 while Trump was in Seattle.

“Any one who visited the lower quarter of the city last night could have known without being in the confidence of [Police] Chief Jackson, or the men who control gambling, that it was not the night a raid was to be made.

“Men were constantly going in and out of the Pacific house and M. & N. rooms, on Washington street, and the policeman who patrolled the beat below might have heard the click of the chips – had he been allowed to do so.” (Seattle P-I)

This article appeared as part of a series about five gambling houses in Pioneer Square and how the police allowed them to flourish. The day after this one the police were shamed into acting like they cared. “One man from each the M & N, People’s theater, C & B, and Pacific houses was taken to police headquarters and allowed to go on depositing $75 bail.”

Later that month the Pacific House made news as a recent parolee from Walla Walla was found walking on Washington Street in a suit four inches too short. The suit had been hanging in a Pacific House room earlier that day.

In December — just a few days before Trump began running ads to sell his restaurant — a man narrowly escaped a shot to the head while he stood in an apartment doorway.

In addition to Trump the Pacific House attracted a variety of normal people. But it had a a rough and seedy population as well. Certainly there is enough material to capture the imagination as a hive of villainy. It would make a good setting for historical fiction.

More images of Pacific House

Reading between the lines, and beyond the edges

Gwenda Blair’s chapter on Frederick Trump in Seattle opened with a brief, broad history of our city’s first forty years. Although the New York Times described Blair’s book as “copiously researched”, her general history sources for the Seattle material were quite dated. End notes reveal that the content came from books from two or three generations ago. Murray Morgan’s Skid Road, Bill Speidel’s Sons of the Profits, Newell & Sherwood’s Totem Tales of Old Seattle, and Sale’s Seattle: Past to Present.

Blair chose what I call the “hookers and gold” version of Seattle history. It’s mainstream history, an unfortunately superficial view of the 1800s that she adopted and used to interpret her primary sources. The bordello Illahee warranted the entire third and fourth paragraphs of a scant four paragraph overview of Seattle from 1851 to 1891. This portrayal of Seattle predisposed readers to the idea that in Seattle, the only business that mattered was selling women’s bodies.

A key passage of Blair’s book described Frederick Trump’s restaurant before he bought it. This was the first time she suggested maybe he was a criminal. Along with later characterizations of his businesses in Monte Cristo, Washington, and Bennett, Yukon Territory, the insinuation that he profited from sex on his premises lead to the label “pimp” that is now being used for Frederick Trump.

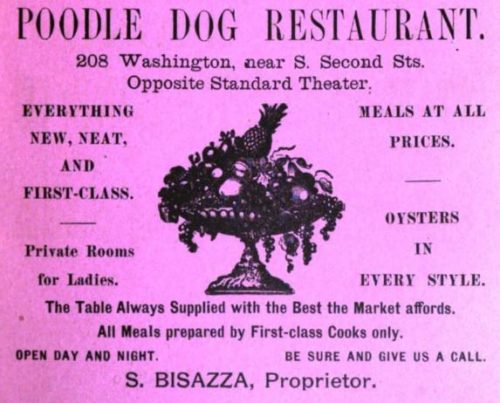

Under [Spiro] Bisazza’s hand, the [restaurant] was called the Poodle Dog. It was a restaurant in those days, too, and specialized in oysters. “Everything new, neat and first-class,” boasted one advertisement. “All Meals prepared by First-class Cooks only.” But the Poodle Dog’s ads also mentioned its other specialty: “Private Rooms for Ladies.” As everyone who read the ads knew, the “ladies” in question were prostitutes. Perhaps Frederick Trump eliminated this service. In all likelihood, though, he did not. (The Trumps, p. 50)

It’s a surprisingly rich statement that deserves close inspection. The content all comes from an advertisement that appeared in the 1890 Polk directory.

Spiro Bisazza

It would be reasonable to read this advertisement and think that the Poodle Dog was a nice restaurant. Can we assemble a profile of Spiro Bisazza that proves he was instead a pimping restauranteur, then? No. Or, at least I wasn’t able to after tracking him and his family in newspapers, directories, censuses, and other public records.

Spiro Bisazza spoke Slovenian natively, born in 1862 in the Kingdom of Dalmatia in the Austrian Empire. On census records it was called Yugoslavia but today Dalmatia is part of Croatia. Unlike Trump, Bisazza was in Seattle prior to the fire. He entered the United States in 1880, and by 1888 he was in Seattle. He owned and operated a restaurant, the Main Street Chop House, just east of Commercial (First Avenue South). According to his obituary he opened the fire-burned district’s first restaurant in a tent. He named it the Poodle Dog and moved it into Hunt’s building when it was completed in 1890. As a cashier Spiro hired Jennie Williams, a young woman who had moved to Seattle from California in 1890. She was 24 and from a large farming family east of Oakland.

Blair reports that Trump purchased the restaurant in November 1891 from another owner who had purchased it within the last year from Bisazza, but I’ve been unable to rediscover her source. In 1892 Bisazza opened another restaurant though, this time in the Citizen’s Market at the southwest corner of Second and University. Jennie went to work at the Rookery restaurant, a block east of Trump’s Dairy. At some point in 1892 Jennie and Spiro traveled to Dalmatia, were wed, and Jennie gave birth to their first son, Victor Spiro Jr. in 1893.

By 1894 they had returned to the US, perhaps living with Jennie’s parents for the birth of their first daughter, Charlotte, who was born in late 1894 in California.

The family moved to the resort town of Lilliwaup, Mason County from 1895 to 1897, where Spiro was the post master. Then somehow they found their way to Minnesota. In April 1901 Bisazza was sentenced to eight months in federal prison for filing for bankruptcy while concealing assets. He had been operating a store in Crookston, Minnesota at a small loss. Meanwhile he slowly concealed cash and shipped merchandise to Seattle, evaporating the store’s assets. (Fitting with the name Crookston, the auctioneer for Bisazza’s assets was arrested for selling without a license.) He was arrested as he was about to board a train to Seattle. Articles about the case described him as “the bankrupt merchant of Crookston”, which has a nice ring to it.

By 1902 the Bisazzas were back in Seattle for the birth of their fourth child, Virginia, but Spiro’s profession had changed drastically to real estate. He must have held on to a good deal of the “lost” money and reinvested it. His sons became shoemakers. Charlotte became a much-liked art teacher at Franklin High. Virginia married and raised a son.

I see nothing that is consistent with Spiro Bisazza leasing day beds to hookers at the Poodle Dog. I could be wrong. I don’t know his full life story, and certainly people are more than their trail of records. But a trail of records is certainly a better basis for speculation than a single phrase open for interpretation in a single ad.

Poodle Dog

When Trump moved to Seattle, MacDougall & Southwick was the leading department store. It was started as the San Francisco Store, part of a noticeable list of Seattle business names inspired by California. Since the 1849 gold rush, San Francisco was the premiere city on the west coast and merchants tried to evoke its image. Many of Seattle’s older residents like J. W. Hunt had been in San Francisco before coming to Seattle, and others like Jennie Bisazza were born into first or second wave families in California and then headed to Seattle after the fire. The names resonated with them.

The Poodle Dog was another business that referenced the golden state. The original Poodle Dog restaurant was in San Francisco and opened in 1849, right at the start of the gold rush. It was a fine French restaurant and reportedly the nicest place in the city. There are many stories claiming to explain what the name meant, but the most believable is that the real name was Le Poulet D’or (golden chicken), which was corrupted by the drawled and slurred speech of miners into Poodle Dog. From the 1860s into the 1900s it also offered high-class facilities for escorts on upper floors.

Here’s how San Francisco historian Jim Smith described the 1860s iteration of the Poodle Dog’s public, lower two floors:

The lavish first floor dining room of the new facility offered public accommodations where a man could safely take his wife and daughter to dine in elegance; a decor in a style torn between the Rococo and Louis XIV styles. Priced at around a dollar, they offered the highest quality cuisine in the city. The second floor hosted private dining rooms suitable for a meeting and dinner with a member or two of the opposite sex; said to be risque [but] not particularly terrible.

If Spiro Bisazza had access to more than just the restaurant space, I’d be more inclined to believe that he was involved in whatever scandalous activities happened further upstairs in San Francisco. But with just the narrow 12 foot by 42 foot room, I can’t imagine anything particularly untoward was going on.

(Fun fact: It wasn’t just Seattle. There was a Poodle Dog in Victoria, B.C. as well. There is still a Poodle Dog restaurant in Fife, and I assume it took its name from San Francisco as well. SF closed in 1922, and Fife opened in 1933. Fife’s is a diner, so the style of food doesn’t seem to have carried outside of California.)

Ladies rooms

Let’s test this line: “As everyone who read the ads knew, the ‘ladies’ in question were prostitutes.”

Gwenda Blair’s book now owns the search results for “private rooms for ladies” on Google. Luckily it’s easy to screen out all of the pages that have repeated pieces of the book. Simply add a ” -trump” and all recent posts filter out. Move the search to an archival database and the results are even more useful. For example, the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America is all old newspapers. Google Books is another good source, mostly material prior to the 1923 copyright cut off. Google itself can be given date scopes. Do that, and a different meaning of “private rooms for ladies” emerges. It’s a luxury that Blair didn’t have when she originally researched the book in the late 90s.

The following quote from a Google search is a good description of the beginnings of the private room. It was part of a review of the beginnings of American restaurants:

With the opening of the Tremont House in 1839, the higher-class hotels began providing a special dining space, a “ladies’ ordinary” as it was called, whose stated purpose was to allow women to avoid the discomfort of taking their meals in predominantly male company. (“American Restaurants and Cuisine in the Mid–Nineteenth Century”, New England Quarterly 2011)

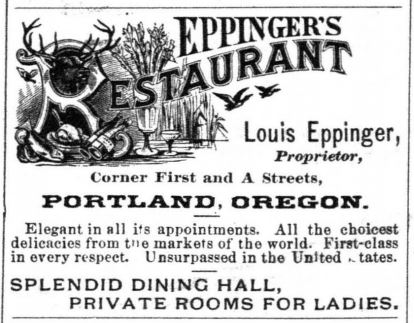

The exact phrase in question appears in this 1883 ad for Eppinger’s, an upscale restaurant in Portland, Oregon.

So far I haven’t found any mention of Eppinger’s that would connect it to illicit activity.

The phrase appears in Chronicling America more than 2500 times before Seattle’s Poodle Dog advertisement. A good chunk of those are the same businesses advertising repeatedly. Here’s one from Oregon:

Eclipse Chop House – Old Mack, the pioneer cook, would respectfully inform the public that he has fitted up the above Chop House, and is prepared to serve up meals and lunch in the best style and at the shortest notice. Balls and parties furnished with suppers, in the best style and on the most reasonable terms. Oysters in every style. Private rooms for ladies. House open all night. (Daily Mountaineer, November 29, 1865)

And another from Oregon:

Italian restaurant – S. Damico & Co – Just opened, newly furnished and first class. Meals served in French, Italian and American styles to order. The table will be supplied at all times with the best the market affords. The well known and gentlemanly steward V. A. Cook will always be on hand with a first class Italian cook, pleased to see his friends. Come and satisfy yourself. Private rooms for ladies. Meals at all hours. The best wines and cigars always on hand. (Daily Astorian, May 21, 1879)

Like Bisazza’s Poodle Dog, Damico’s restaurant mentioned oysters in other advertisements.

Here’s one from Hawaii:

E. J. Meller – Ice Cream Parlors and Candy Manufactory. The choicest candies and Ice Cream constantly on hand, private rooms for ladies and families. (Daily Astorian, November 25, 1886)

And then there’s this one from a decade later, for a restaurant in Nevada named after the Hebrew word for “watchtower”.

“For a nice Sunday dinner — the best in town — try the Mizpah cafe and grill. Private rooms for ladies and families.” (Tonopah Bonanza, Nov 4, 1905)

The one source I can find on the other side is a moralist screed from 1907, The Booze Route. It has a great subtitle: “A Reform Book on Some of the Up-to-date Evils of the Age”. Head to page 94 and you’ll find a long claim that every place that served alcohol and offered space to women was allowing innocent girls to be seduced.

I bet it happened. But how prevalent was this activity? It should take strong evidence to posthumously tie someone to illegal and immoral business dealings. One harmless phrase in one advertisement by a previous owner of the business… that’s not enough.

Dairy Restaurant, Dairy Kitchen

The Poodle Dog was such a unique name. Why would Frederick Trump rename it? Where did he get the name Dairy Restaurant?

Nowadays the phrase “dairy restaurant” refers to a kosher Jewish restaurant that does not serve meat. That term apparently was not contemporary to Trump’s restaurant. The kosher term appeared a decade later when Ratner’s dairy restaurant opened in New York’s Lower East Side in 1905.

So if it didn’t refer to a general class of restaurant, there must have been something else. Indeed, there was a restaurant in New York called the Dairy Kitchen. Here’s the description of it from an 1892 guide to the city (not in the kosher section, by the way):

The Dairy Kitchen in 14th Street is a curiosity. It is an enormous establishment where several thousand people are fed every day. There is orchestral music day and evening, and much glitter and show. The prices are moderate, and the food and service correspond.

A 1900 menu from the Dairy Kitchen has been shared online by the New York Public Library. It included tenderloin steak, so the restaurant clearly wasn’t a kosher dairy. It also included a full address, 48 14th Street. That was only a short seven block walk from one of the places the Trumps lived before Frederick moved to Seattle. And if it was such a spectacle, he must have known about it.

A New York Dairy Kitchen operated in Ottawa in the 1890s, so the name had weight to it.

A broken frame

Allow me a digression.

Stroud Avenue

My great grandmother Stella Stroud arrived in Seattle soon after Frederick Trump. In 1892 she came with her parents Fred and Arabella and two siblings. They weren’t in the very first wave after the fire, but they are part of Seattle’s 1890s post-fire narrative. Fred worked in the office of real estate developer John Wallingford. Wallingford has an entire neighborhood named after him now. Somehow Fred Stroud managed to get a street named after himself in one of Wallingford’s plats. Stroud Avenue is one of the few names that survived those 1895 street renames, and it’s still on the northeast corner of Green Lake today.

Arabella sued for divorce from Fred in 1895, in part charging that he was “consorting with lewd women.” Fred moved to Stockton, California and immediately remarried. He became a successful paint supplier. Arabella became a devoted member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union movement and up until her death in 1905 was active in the Prohibition Alliance in Wisconsin. Before they left Seattle, Stella took work in the Washington Shoe Company on Jackson as a shoe fitter.

In the oversimplified “hookers and gold” narrative of Pioneer Square, all of Seattle’s vice happened in that one neighborhood and all that happened in that district was vice. How could my great, great grandfather have wronged my great, great grandmother if he was way up at Green Lake? Surely there was some mistake. Since my great grandmother was working with textiles below Washington Street, surely this meant she was forced into prostitution after her father abandoned them?

No, that is asinine. A city is a complex place. The version of Seattle history that is all about upstanding, moneyed white men is terribly incomplete. But if we become convinced that every “seamstress” or “dressmaker” was really paying for food and board through sex, we are buying into yet another sexist narrative. Unless all of these prostitutes were just naked all the time, there was a real need for seamstresses and dressmakers in a booming city. Among the group that we call prostitutes there had to be range of activities, with friendly conversation on one end and sex on the other. The truth can be neither black nor white.

Mayor Ronald

Historians owe the citizens of Seattle a comprehensive chronicle of vice and the efforts to end it. The 1965 book The Dry Years took a look at the battle against alcohol at the state level from the earliest years of Washington Territory. I don’t know of any attempt to update it, despite the dramatic increase in primary materials available recently. Progressive efforts against prostitution and gambling were sometimes separate and sometimes entangled with the prohibition movement.

One attempt to clean up Seattle happened while Fredrick Trump was still here. Mayor James T. Ronald campaigned in an upstart Democratic ticket on a platform of closing down the gambling houses south of Mill Street (Yesler Way). He took office on March 31, 1892 and immediately put his campaign promise into effect. After forcing all five gambling houses to close he sacked his corrupt chief of police.

James T. Ronald is yet another character in Seattle history that somehow is only barely mentioned. His memoirs were published by the Shoreline Historical Society in 2003, but we have no third-party biography to fill in the gaps in his story. For example, Bill Speidel mentioned in Sons of the Profits that Ronald was attorney for madame Lou Graham when she was arrested on suspicion of prostitution. The episode was not mentioned by Ronald in his autobiography.

Online, the only discussion of Ronald is tied to the 2014 designation of his Leschi neighborhood home as an official Seattle landmark. He has no Wikipedia page nor HistoryLink profile. This has led to silly mistakes like claims that he resigned after one year in office in the recent book Seattle Justice. Considering his actions on gambling alone he deserves a closer look. Add in the fact he saved city engineer R. H. Thomson from a politically driven dismissal by the Board of Public Works, and that he oversaw the first attempt at a park system for Seattle, and it’s baffling that he is not more discussed.

In his memoir Ronald said that he closed more than the gambling houses:

Before the end of my first week, [vice districts] Whitechapel and Blackchapel were absolutely tenantless — not a soul was left as a reminder of their “glory and splendor”… [of] vice, filth and ribaldry. Yet, I well recall how numerous people criticized me for closing these vicious and criminal resorts, declaring that I was ruining the city by driving loggers and visitors to Tacoma or to other places, where they could spend their money enjoying themselves.

I can recall now the names of some leading merchants, some of them church leaders, who began calling on me, and asking me confidentially if I would permit gambling and sporting to operate. I always told them to go to the council and have the ordinances prohibiting such sports repealed, and I would allow them to operate. (Reflections along the Wayside of Life)

As I mentioned in the description of the Pacific House, the Seattle P-I ran articles throughout 1892 mocking the police because of continued activity of gambling houses. According to Ronald in his memoir, the papers were all against him, either because they were Republican owned or because he refused to toe the Democrat party line. The P-I mocked him, not the police. We may never know the complete truth of Pioneer Square while Frederick Trump was in Seattle, but it’s exciting that historians can now recreate the dueling narratives.

Either way, I think it’s more interesting to imagine Frederick Trump in a conflicted Seattle than in one that was simply overrun with vice. If he really left Seattle and became more entangled with crime, perhaps he saw here that it pays much better before law and order is established.

(Fun facts: James T. Ronald’s first home in Seattle was at Pike and Terry. The footnotes and editorial comments in the 2003 edition of his memoirs incorrectly relabel Tenth Street as Tenth Avenue — the street name actually changed to Terry Avenue. Also to correct an even older error, the 1884-1885 city directory lists him at Prince Street, but per my 1895 street rename key that was actually Prince William Street, now Spruce Street.)

Bella Rosenbaum

Let me step into the history of another family to further illustrate how the “hookers and gold” history of Seattle is incredibly one-dimensional.

In 1893, a young woman named Bella Weretnikow moved to Seattle with her parents. Her father became immediately entrenched in the orthodox Jewish community, contributing to the group that later formed Bikur Cholom. Her mother opened a second hand goods store on Main just east of Commercial (First Avenue South). Bella helped run the store while going to high school and then entering the University of Washington at the young age of 16.

I learned about Bella while researching a story and lucked out when I contacted her granddaughter Judith Rosenthal. Judith sent me copies of Bella Weretnikow Rosenbaum’s unpublished autobiography My Life. Bella’s description of Pioneer Square in the 1890s is precious and perfectly illustrates the need for an integrated history of both corruption and commerce. I will quote it at length.

Skid Road had indeed become the “hotbed of crime and vice.” Its so-called “Dens of Iniquity” flourished openly. And, in order to convince themselves how really bad Skid Road was, some of Seattle’s most prominent citizens could frequently be found patronizing its bars. The saloons which had the longest bars and served the most free food were the most popular and best patronized.

Thundering orators in the finest pulpits on the hills ranted and raved against Skid Road, insisting it be closed. But they offered no substitute for its popular saloons and dance halls. Politicians and City Fathers knew that such places had to exist in frontier and waterfront towns, and did their best to keep such order as they could. They knew that there had to be places where the ever-increasing horde of transients, miners, sailors and strangers would find a welcome, where they could congregate and talk. They did not all get drunk, and those that did were promptly eliminated by the so-called “bouncer.” This procedure was followed even in the exclusive club known as Sutherland’s Bar, where the politicians and the high class gentry were wont to gather and often drank a little too much for their own good.

When these transient men arrived in town, after being away from civilization for many months, they were all out for a roaring good time; above all they wanted human companionship, and the other things they had missed for such a long stretch of time. They brought with them their pay, usually a big wad of bills, which they seemed bent on spending as fast as possible. In order to do so, they invariably made a bee line for the nearest saloon. These saloons, of course, bore no resemblance to the fashionable bars of the Eastern states. As a matter of fact, there was no other place for these land-hungry sailors and loggers to congregate. Nowhere else were they welcome. Nowhere else would they find, waiting for them, bright lights and gay paintings (mostly, of course, life-sized nudes). There were many, more serious-minded sailors and loggers who preferred to remain sober, and gathered in these places to discuss their pay, their working conditions, their bosses – in fact all such topics, as are now being discussed by the same type of worker in the various clubs, which have since been organized. Also, of course, they discussed more personal matters, their prowess with other men, in fights they had had, and particularly their prowess with women of their own kind and otherwise, and also their hopes and ambitions, and plans for the future.

Here, too, they found card games, could get news about prize fighters and heard many tales about foreign parts which had been visited by members of their group. When some of the men did become quarrelsome or intoxicated, they were promptly and skillfully evicted by a colorful type of employee, known as a “bouncer.” The men who were bounced out of a saloon wandered about, and were nearly always picked up by the owner, or a clerk, of one of the waterfront stores. They were taken in and allowed to sleep it off, on a pile of blankets behind the counter, or in back of the store. By this means the shopkeeper often became the best friend of these lost wanderers. There was a helper in my mother’s store whose business it was to pick up these men when he could, and take care of them. Otherwise, they might have been “shanghaied” or killed for the wads of money they carried on their persons.

A woman in business on the waterfront was rather unusual in those days, but many a sailor and logger learned to trust my mother and give her all the respect and deference they would have given their own mothers. I have seen these big, strong men, when sober, become very shy and bashful, especially in the presence of a decent woman. They seemed to have an innate decency and dignity that I have often found lacking in men of education and polish. My mother became their confidante and their banker; besides buying their outfits at our store, they would leave certain amounts of cash in her care to tide them over when they went broke, until they could get new jobs. I happen to know all this because I was the bookkeeper who kept charge and record of these accounts; and the men were most grateful to her.

These shopkeepers and merchants of Skid Road in Seattle received little, if any recognition, yet they made a decided impression on the growth and development of the city. The business men of Skid Road operated their stores right alongside the saloons, pool halls, lodging houses, etc. These shopkeepers were all good Jews, had all served their apprenticeship in the east or midwest and once again became pioneers in this far western land. As Jews, they had brought with them their heritage of the Torah, with its highest and oldest code of ethics and morals, and thus their nearness to all this vice and depravity seemed to make no more impression on them, or their way of life, than water on a duck’s back. Later with the advent of prosperity, brought on by the Klondike gold rush, most of these small merchants left Skid Road and branched out on First and Second Avenues, with fine new stores and all new merchandise. Also, they built new and better homes up on the hills, synagogues, and Hebrew schools. They sent their children to High School and to University, and thus raised the next generation to be lawyers, doctors, dentists, and leading merchants of the thriving city of Seattle. (My Life, pp. 29-31)

Of course I am not saying Frederick Trump — even with his German name Frederich Drumpf — was Jewish. Neither was Spiro Bisazza. Clearly Bella’s description contrasted merchants on one hand and service and entertainment on the other. But the word “restaurant” doesn’t appear anywhere in her work. It’s unclear if she would lump them in with the free-food saloons, or if they were indeed more upstanding. It’s completely clear, though, that it’s unfair and incorrect to indict every business south of Washington Street as a component in a massive liquor, drug, and indentured sex slave enterprise.

There is still a burden of proof that must be met. It hasn’t been met for 1891 to 1893.

The point

Guilt by co-location is not a thing. We can’t assume Trump was involved in crime simply because we know it happened on the street with his restaurant.

There is a ton of Seattle history that is poorly understood. It’s thrilling to do research and feel that I know something no one has understood in decades. But it’s also scary, because I know that there is no history litmus test for claims about the past.

It’s sad that so many people are ready to accept ubiquitous prostitution as Pioneer Square’s one-dimensional story, and that we’re happy to pay a nickel to laugh about vice. If the story was about current affairs most people would be asking for more context.

Worst of all, Nate Silver forecast this week that Donald Trump has a 20% chance of becoming our next President. We need to shine a light on all of the reasons that should never be allowed to happen, but instead we waste time trying to belittle him when we call his grandfather a pimp.

(Also, it’s not okay to coopt the built history of Chinatown.)

Who am I to judge?

My name is Rob Ketcherside. My trade is in the tech industry. I work at EMC’s (soon to be Dell’s) Seattle office a few blocks from where Trump’s restaurant was. But I have a not-so-secret identity, researching and writing Seattle history at night. I’ve got one book, Lost Seattle. I write a regular history column for my neighborhood’s website, Capitol Hill Seattle Blog. I write about whatever catches my fancy (recently grocery store history for some reason) on this website, ba-kground.com. I’m also a member of Seattle’s Landmarks Preservation Board, casting one vote to decide the fate of our relics.

I read the “Donald Trump’s grandfather was a pimp and tax-evader” article on June 14th. After three weeks of research and writing I’m finally hitting the publish button. I hope you’ve enjoyed this lengthy exploration of a few scant pages out of a six hundred page triple-biography. I hope you have a rekindled skepticism of single-source history, along with an awareness of how many stories of our joint past still wait to be told, and to be retold.

Now it’s time for me to get some sleep.

(Thanks to my friend Tom Heuser for capturing the 1937 assessor photos!)

Further reading

- Denny Hotel construction lasted one long decade

- Was Seattle named Duwamps?

- Seattle’s Beacon Hill, Redefined

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for you meticulous research.

Thank you for digging and trying to clear this up. When I read about the leap from “Private rooms for ladies” to the assumption that it meant prostitution, I thought: “No, that’s not right.”

Here’s why:

In 1975, worked as a bus-boy and janitor at the old Brasserie Pittsbourg in Pioneer Square, located in the Pioneer Building, just off Yesler near First Avenue. To enter the restaurant, which was a Seattle institution for years, customers would go down a few steps from Pioneer Square, descending into an entry alcove. The entrance was, and is, located a few feet to the right of the big ashlar stone arch building entry of Pioneer Building. Walking down the steps to Brasserie Pittsbourg, and just before walking through the restaurant doorway, one could see a stenciled sign on the plate glass just to the left: “Tables for ladies”.

I always assumed the stencil was left from a prior tenant, before Francois Kissel’s venerable Brasserie Pittsbourg. In the rough and tumble frontier days, I assumed, women having lunch together, or alone, might prefer to be away from the lonely and tactless sailors and loggers and ranchers, who might jump to the conclusion that a woman dining alone in the city was… working.

So the finer restaurants and tearooms might provide places for a better class of ladies to get away from the rowdier element.

Last time I looked, the semi-basement retail space that was once Brasserie Pittsbourg was an antique mall. And I bet that stencil is still there on the window. Look to your left as you descend the stairs from Pioneer Square into the antique mall: “Tables for ladies”.

I don’t think it refers to ladies of the evening…

Brian, thank you for the comment! That’s fantastic, I’ll stop by tomorrow to see if it’s still there. I’m glad I’m not the only one who thought the claim struck a sour note.

The stencil is still on the window (for now). The Pioneer Building has new owners and they are doing a big renovation, hopefully they leave the stencil where it is.

Amy thank you for the comment! I stopped by and took a look and to me the window itself and the lettering look modern. Rather than a stencil, I think the letters are perhaps adhesive or heat applied.

However that phrase was very popular in the 1920s so I wonder if they put the text back on after replacing a window, perhaps as far back as the 1970s restoration. I hope to find out more!

Brilliant research. A friend was interested in 208 2nd and posted his conjecture on Facebook. However another friend posted your correct information. Keep on digging into the history of our town. You get a Bravo from me!

A lot of interesting information here. Thank you!

Fantastic piece of work, Rob! Thanks a lot!

Just a small comment: There is a Beck & Paul’s birdseye map of Seattle (1884) – as you probably know.

On this map you’ll find the PACIFIC HOUSE (Index Nr 14) at the corner of Jackson Street / 2nd Str.:

http://vallandingham.me/seattle_maps/maps/seattle_puget_sound_1884/

It might be, that they rebuilt the original PACIFIC HOUSE at Washington / 2nd Str. where Friedrich Trump lived? Or Gwenda Blair would be right and he had to walk one block to work…

Two questions (very specific, sorry): Do you know, where exactly the DAIRY RESTAURANT as tent restaurant was located? I can’t figure it out.

And secondly: Is it right, that the ILLAHEE (aka THE SAWDUST PILE) was also located at the corner of Washington Str / 2nd Str.? So the ILLAHEE would have been exactly opposite Trump’s DAIRY RESTAURANT?

Thanks again! I really appreciate your fantastic work!

André Georgi (Germany)

André, thank you for your compliments and for reading through.

The answer to all of your questions is, “time”.

You’re not wrong, it’s just that Seattle changed very quickly. A hotel named Pacific House was at the southwest corner of 2nd (later Occidental) and Main in 1887. Not Jackson as you mentioned, but also not Washington as in my story. Specifically, the 1887 guide has it at “s[outh] w[est] cor[ner] Main and 2nd” (Occidental).

However, Pioneer Square burned down in 1889. I don’t know why the new Pacific House was a block away. Maybe that story is hidden and waiting for us in the old Seattle Post-Intelligencer issues. But I’m sure that after the fire the hotel Pacific House was on the northwest corner of 2nd (Occidental) and Washington.

Since I published my article, the Library of Congress has shared old Sanborn fire insurance maps. So you can look at them yourself. Here is the map for 1893 that includes the west side of 2nd (Occidental) and Washington: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4284sm.g4284sm_g09315189301/?sp=25&r=0.335,0.061,0.99,0.577,0 … Note how the addresses are written next to each door.

The 1893 Polk Seattle city directory has this address for Pacific House, “119 S 2nd”. That is a starecase leading up from the street, just north of the northwest corner of Washington and 2nd (Occidental).

Illahee is even older. It was long, long gone by the time Frederick came to Seattle. I can’t quickly find a date for when Illahee was demolished, but it was already more a legend than a part of history by the 1890s.

I don’t know where any of the tents were set up. I have never seen any sort of directory or description.

When my mother passed away my father found a document/bill from Feb 20th 1890. The bill is written on letterhead from “Fred E. Sanders Read Estate & Investment Securities, Seattle W.T.” to what says IJ K stall Eaq Blekekey Wash.

While trying to research it. I stumbled on this piece. Its beautifully written and very informative. Thank you.

I don’t know exactly what this bill/document is about exactly. It’s hand written and a bit hard to read. Please feel free to email me if you would like to help me figure out this little slice of history.