Mount Jennings was as close to a spite mound as you’ll get in Ballard, and had more spite than the mounds in Seattle.

It sat for five years on Ballard Avenue, in front of the property of Arthur Jennings. As we’ve covered, he designed the Denny Hotel. He also owned property in Ballard and platted a tract in the northwest part of that city. And he reviled paying to improve Ballard’s streets.

This is part 7 of a 7-part series Summiting Mount Jennings. You could start at part one.

Back in 1895 everyone who had been to Ballard knew about the mound in the city’s center. You couldn’t avoid seeing it, it was memorable, and everyone knew its name and part of its story.

Mount Jennings’ peak

The Seattle P-I updated everyone that the situation was finally coming to an end in the summer of 1895:

Mount Jennings is named after Arthur B. Jennings, of New York, who wanted damages for the grading of Ballard avenue in front of his lot… About one-fourth of the mound has been removed by the West street railway company and another fourth by the Stimson Mill Company, so that it will cost only about $50 to remove the remainder. As the cost of a suit would be as much, the council favors removal at the city’s cost, unless a bad precedent is set.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 15, 1895, p2.

Sadly I have found no photographs of Mount Jennings, but there are plenty of details in the old Seattle P-I and more in local archives. And the Seattle Municipal Archives holds all of the records of the City of Ballard.

Those City of Ballard records contain several letters from Arthur and his brothers William and Emerson to the city whining about taxes and fees. In the records’ street engineering files, under Ballard Avenue, there are also partial records of the lawsuit between Jennings and the city which led to his “spite” mound.

The full records of the lawsuit are on file at the Washington State Archives, an easy lookup if you know the case number. Easier if you have a friend like Valarie Bunn who goes to dig them up for you.

Thomson’s forced erosion plan

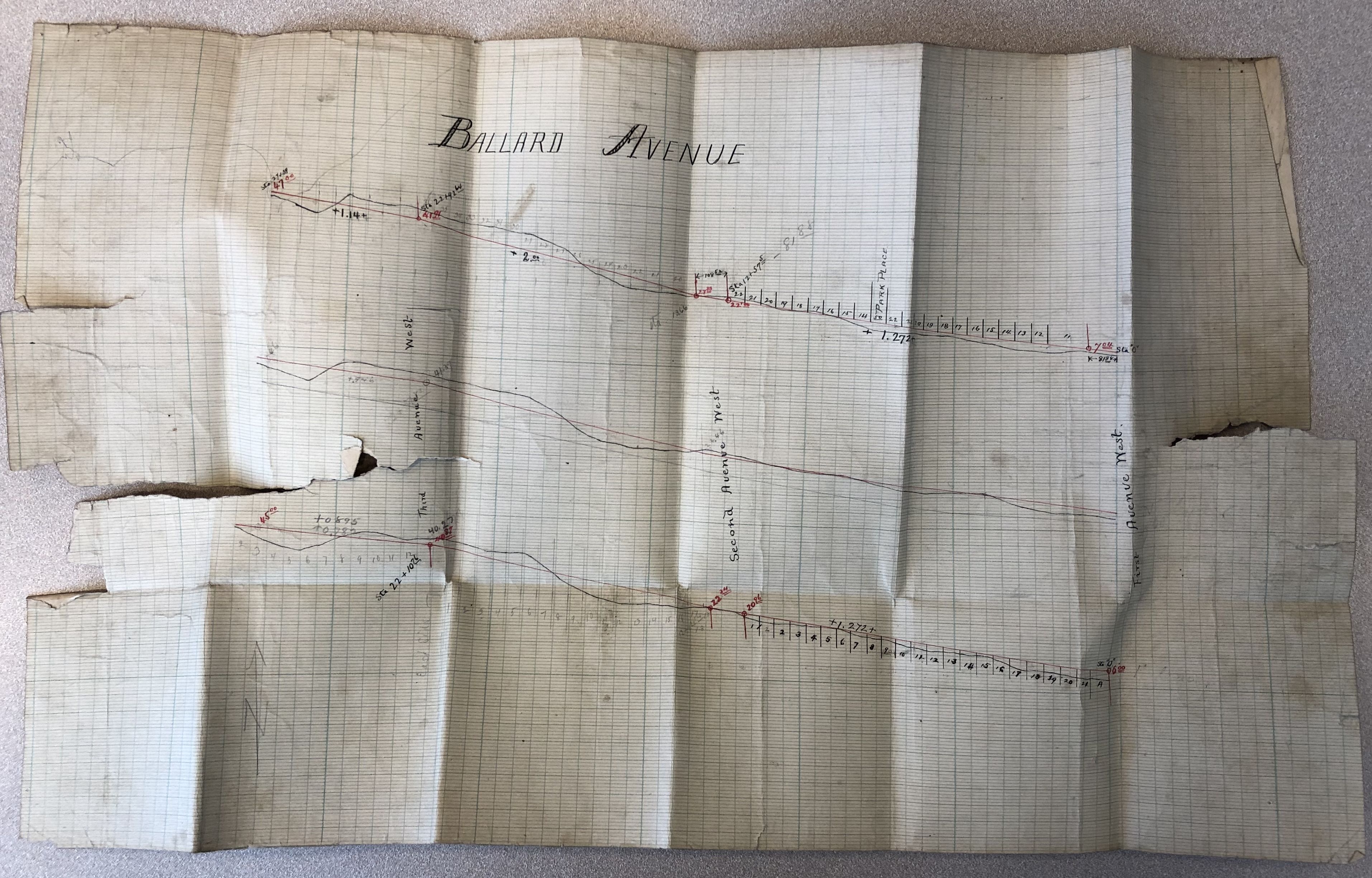

In one of its first acts, the City of Ballard hired local engineer R. H. Thomson to prepare a plan for improving central Ballard’s streets. Thomson later became famous as Seattle’s regrade engineer. He did it in Ballard first, though at a smaller scale.

In May 1890 he submitted the designs for leveling Ballard Avenue and adding sidewalk planking. The plans were approved by city ordinance 23, and the originals are still on file in seldom-opened boxes at the Seattle Municipal Archives.

Jennings and several neighbors sued the city, complaining that access to their buildings would be much worse if the street were many feet below them. Per the August 1895 Seattle P-I article, Jennings was most bothered by being asked to pay $150 towards street improvements.

Mountain range becomes single mount

The other plaintiffs each toured their property with engineer Thomson and were suddenly convinced that the new grade was the best thing for them and the city. We don’t know if it was a fatalistic decision, if they were truly swayed by Thomson, or if perhaps their peers followed them on the tour, pressuring them to go with what benefited the group most.

Whatever drove their thinking, everyone but Jennings decided to drop their case.

Jennings persevered, complaining that his building would need to be pushed back and the front door would require five feet of steps. In their refutation of charges, the Town of Ballard claimed that the case was brought “for the mere gratification of personal spite and not out of any honest belief or conviction that said property… will be damaged.” The city, then, claimed this indeed was an example of a spite mound, and used the word itself!

Jennings won. I’ll never get back the time I spent reading the court case’s legalese. We can assume that their souls are tortured over the months they spent in the courthouse debating it. In the end, the court agreed that Jennings would be harmed by the lower grade, and could not be forced to pay to have his half of the street lowered.

Mount Jennings rises

The street improvements went on without him.

The court allowed the city to proceed with its grading of Ballard Avenue, but with no changes to the street in front of Jennings’ lot. The opposite side of the street was carved away as well, leaving a mound across half of the street. This is because technically every property extends to the middle of the adjoining public right-of-way.

Improvements to Ballard Avenue included planked wood sidewalks. So to climb Mount Jennings the court ordered the city to build a flight of stairs:

“… erect a substantial and serviceable flight of steps rising from the portion of said Ballard Avenue so graded and cut down and either side of the frontage of the plaintiff’s said lot to the portion of said Ballard Avenue to be left undisturbed by this order… which flight of steps will be on the line of the sidewalk of said Ballard Avenue… and the width of the steps shall be the same as the full width of the sidewalk.”

King County Superior Court Case 8641 file “Substitution of alleyways & appearance”, March 3, 1893

The descriptions are strong, but it’s still difficult to imagine this mound in the middle of the road.

Mount Jennings was five feet high. It jutted out thirty-three feet into the center of the street, and continued back one hundred feet until the end of Jennings’ lot. To traverse from one side of Mount Jennings to the other covered fifty feet up the street.

Siting Mount Jennings

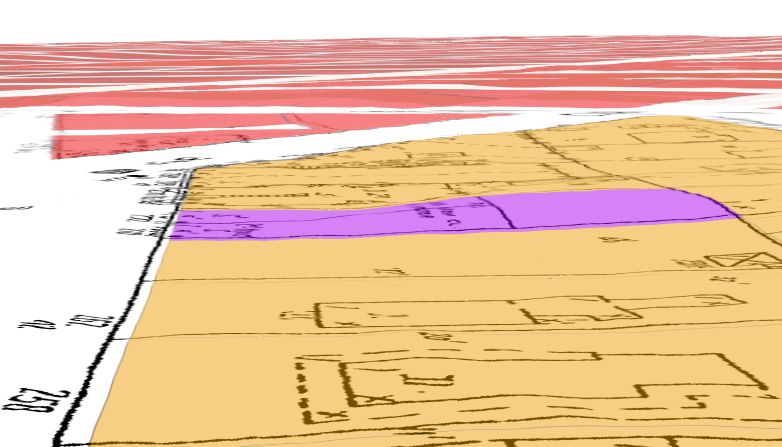

Per the lawsuit’s initial court filing, Mount Jennings was located at Gilman Park Addition block 74, lot 34, which Arthur Jennings bought on November 18, 1889.

Today that lot’s address is 5344 Ballard Avenue Northwest. It’s currently home to women’s clothier Horseshoe. The building there today is from 1927 per King County’s 1937 property data.

Although Ballard truly removed Mount Jennings from Ballard Avenue in 1895, my friend Lorn Fant discovered that data used by GIS firm ESRI still shows a lump in the back of the lot.

I stopped by Horseshoe recently to poke around and chat. There is no remnant or memory of Mount Jennings. The lot no longer rises in the back. Actually, they said, there is a step down from the front of the building to the back.

Looking at aerial imagery today, it’s clear that the building has a later addition. And looking at 1936 aerial photos, it’s clear that there really was a lump there still behind the building. So Arthur Jennings went cheap and had the minimum footprint of his lot excavated in 1895 when the street was lowered.

Jennings building, 1890-1927

In 1890 Jennings built a single story brick commercial building on his lot. On one hand there is no direct evidence that Jennings had a hand in its design. It could have been simply an investment property. On the other hand it was more than a simple box, and it stood out from others in the commercial district.

Jennings certainly chose a design, and it would be easy for him to draw it. He may have described a building and sketched it, then someone else such as Albert Wickersham could have finished the plans.

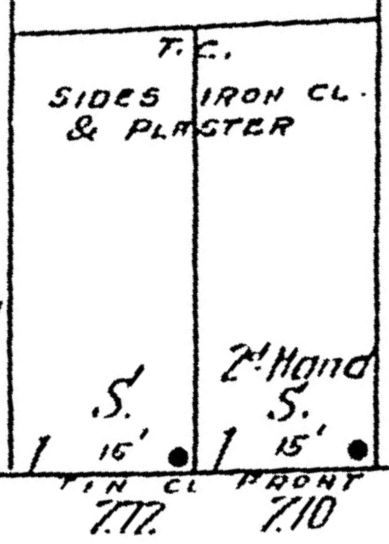

The Jennings building had two store fronts, addressed 270 and 272 Ballard Ave until 1907, and 5342 and 5344 Ballard Ave N.W. afterward. The building had a bay window on the outside of each storefront. According to the 1904 Sanborn map the storefronts were covered in tin. The sides of the building were plaster clad in iron. No other nearby buildings had annotations like this.

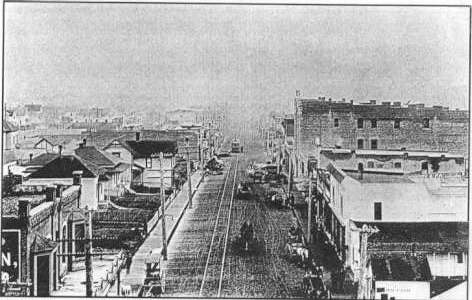

There is only one photograph I’ve found that includes Jennings’ building. I was pointed to it by Cass O’Callaghan of the Ballard Historical Society. It’s a photo taken from the 1899 Ballard City Hall, which remains today at the northwest end of Ballard Avenue. The photo looks to the southeast.

On the far left, at the bottom corner, Jennings’ building is visible. We see the storefronts, an open area in front of them, then what appears to be a decorative fence in front of the sidewalk.

The Jennings building was eventually replaced by a new building in 1927, built by Ballard Commercial Club president C. A. Paul.

Jennings building tenants

The first tenants were grocers Smith & Kintz. The strongest argument in the trial over Mount Jennings was the hardship of customers and tenants reaching the store up five feet. Grocers require a constant stream of foot traffic and deliveries, so its easy to see how the court ruled in Jennings’ favor.

When the Sanborn fire insurance company visited in 1904, the building was occupied by hardware store Christen & Hansberry in the left or western storefront, 272. Ballard Furniture Company, a used furniture store, was in the right storefront, 270.

Later tenants included baker Theo Soyland, the publisher of the Ballard Record (1909-1910), and Ballard’s original Bartell Drugs location (1910-1911).

Fall of Mount Jennings

But for better or worse, Mount Jennings was carved away by the City of Ballard in 1895. The August 1895 Seattle P-I shared that Jennings no longer objected to removing the dirt. “The council has ever since been striving to remove the mountain and make Mr. Jennings pay the cost, but though he is willing to have it removed he objects to the paying.” He refused to pay $125 to have it excavated. So the city council voted to pay themselves, and Mount Jennings was no more.

We don’t know exactly when Jennings sold 5344 Ballard Avenue N.W. But he probably still held it in 1910. That’s when Ballard’s newspaper, the Ballard Record, moved in. We’ll stick with that, because it makes a tidy end.

Arthur Jennings’ son was an organist, but his nephews continued the family business, running printing companies in New York and Pennsylvania.

Further reading

- Previous: Mount Jennings, Ballard’s spite mound, part six

- Rebuilding Seattle after the Great Fire

- The tunnel from Capitol Hill (on CHS Blog)

- Undermining the Republican Senator from Melrose (on CHS Blog)

Extra Content

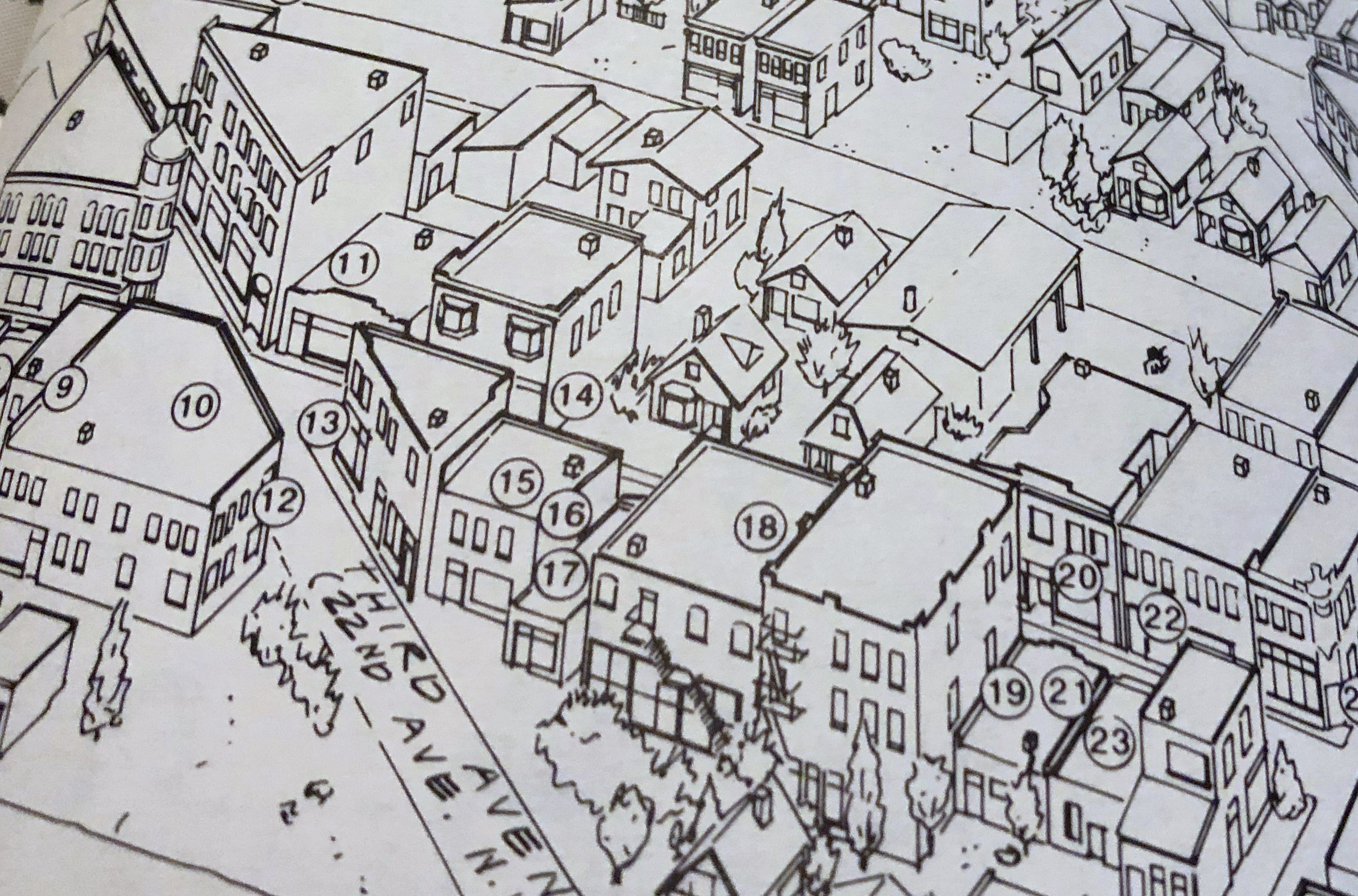

While researching Arthur Jennings’ building, I discovered an error. There is a fantastic birds-eye view of central Ballard that appears in the generally fantastic history tome Passport to Ballard. However, at least the north side of Ballard Avenue is inaccurate.

In the below snippet of the map, #14 represents William Kurth, machinist. He was located in the lefhand storefront, 272, of Arthur Jennings’ building around 1906. The map correctly shows his address.

However, Arthur Jennings’ building is missing! Also there should be an empty lot between Jennings’ building and the house to the right of 14. There are two other empty lots missing on the block further to the right.

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Love this history!

Small error on the engineering drawing caption. It reads “Left is east.’ Should read “Left is west.’ As the top is north, the bottom south making east to the right and west to the left.

Woops, thank you! I’ve fixed that.

Rob,

Wow talk about making a mountain out of a molehill. I think you wrote that “Mount” Jennings was all of five feet high. Or did I read that incorrectly.

Great research and thanks for sharing all of this.

David

Yes! Five feet, haha!