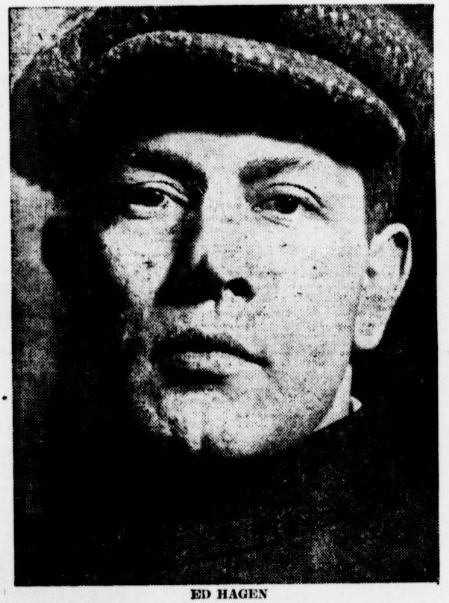

Ed Hagen got away with the greatest crime: stealing history. Casual reading of Prohibition-era newspapers has led Seattle historians to narrowly remember him as the “pugilist policeman”, as a benevolent, bungling bootlegger, and as a hero of the people.

But Hagen’s escapades were not benign. He used his patrol car and his service revolver to extort businesses, and at his worst he used them to kill Black men.

Coming to Seattle

Edward Joseph Hagen was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1887, one of 11 children of Prussian immigrants Maria Steckner and carpenter Robert Hagen. The family moved to Seattle soon after the Great Fire of 1889, when carpenters and other tradespeople were in high demand to rebuild the city.

Hagen didn’t make it past elementary school. By age 15 he already had his own entry in the city directory, still living with his parents but working as a clerk. And by age 18 he found the profession that he carried the longest, working as a baker for N. Henry St. Germain’s Pike Place Market store.

Ed Hagen’s parallel careers

While working as a baker Hagen apparently began training as an amateur boxer. He spent some time in the San Francisco area sparring and betting on himself in 1906 and 1907.

Hagen returned to Seattle and made a big change, joining the police force in 1907 at age 20. He began news-worthy amateur boxing at the same time. In 1909 he attempted to switch to paid, professional bouts. But while preparing to box converted wrestler Dr. Ben Roller, Hagen faced an ultimatum from his police chief on choosing the bout or his career. Hagen skipped that boxing match but later found opportunities to sidestep his leadership and land matches over the years.

By 1910 Hagen’s police leadership already knew him well as a dirty cop. They suspended him for accepting bribes, and then for failure to bring criminals to jail after they bribed him. He quit later that year and resumed his boxing career until mid-1911. Then the police department accepted him back as a police officer.

Ed Hagen married Alice Vaughn in 1908. On the marriage certificate he listed his profession as “policeman”. But he had split loyalties. In August 1910, when Alice gave birth to their son, they named him after boxer Stanley Ketchel.

Hagen became a well-known officer because of his boxing as well as his reckless approach to crimefighting. This culminated in a Madrona Park shootout in September 1915.

Working his Madrona beat, Hagen stepped off the streetcar and spotted two suspicious characters. They caught his attention because of reports of two men robbing residents and streetcar conductors in the area. He asked them to halt and they immediately fired at him, hitting him twice. Hagen fired back but missed. One of the bullets hit his humerus, the upper arm bone, and broke it. Doctors said his boxing career was finally over.

Ed Hagen starts bootlegging

On New Years Day 1916, Prohibition in Washington State began, the ban of alcohol sale and consumption starting well in advance of the national Constitutional amendment. Ed Hagen’s involvement in criminal bootlegging began as soon as it was a crime.

That same year he made headlines for accepting bribes from bootleggers. While under suspension he miraculously learned the identities of a bank robbing gang and gave information leading to their arrest. Coupled with the bribery witness in his case coincidentally vanishing and the charges dismissed, cracking the high-profile case got him his job back.

In March 1917 Hagen nearly killed an unarmed man. He decided something was fishy about a normal situation: two Chinese American men in Chinatown early in the morning. Hagen said that he told them to stop, and when they didn’t, he pulled out his revolver.

He shot Woo Quan in the back. Luckily it only hit his shoulder, and Quan recovered. There was no crime in progress, nothing amiss. But Hagen continued his job, and continued his beat nonetheless.

Hagen’s crimes and his court cases began to overlap and intertwine, leaving a tangled web in historical papers.

Two months later Hagen faced suspension again on reopened charges from the 1916 bribes. His first trial resulted in a hung jury, and then his second in acquittal in October. The day of his acquittal the Chief of Police fired him, after apparently not believing Hagen’s side of the story. But Hagen sued and won his job back in January, reinstated by the civil service board with eight months’ back pay.

He didn’t deserve that money, though. Because he easily found work during his suspension. Two of the jobs he picked up made the news. First, he worked as a bodyguard for the “Chinese Masons”, the unified Bow Leong-Bing Kung tong. And secondly, he also briefly reinvigorated his professional boxing career. He challenged and lost to the Pacific coast heavyweight champion Chet McIntyre at the Seattle Press Club in October 1917.

Ed Hagen kills men

Hagen pulled off a few more headline-grabbing stunts before his new side job, crime, caught up with him.

Despite being a bootlegging middleman himself, Hagen convinced the public that he was a defender against bootlegging. It seems much more likely that he was using his police officer’s shield to enforce authority of his own, perhaps extorting protection money or protecting his sales area.

His racket led to two major spectacles, one with a tragic end, in June 1918.

On June 14, Hagen and his partner, fellow dirty cop Tom Clark, interrupted club owner Frank Smith’s purchase of whiskey from a middleman at 12th and Jackson. Hagen and Clark scared Smith into fleeing. They chased his car all over the central district and southeast Seattle. Smith rolled his car in a turn and died, his neck broken. (A profile of Frank Smith appears this site.)

Just a few days after Frank Smith’s death, Hagen and Clark interrupted another alcohol purchase. Again at 12th and Jackson, they stopped P. J. O’Donnell, owner of the Arcade Hotel. Again the transaction was a large quantity of whiskey. O’Donnell fled like Smith. Hagen pulled out his revolver and shot at O’Donnell’s car, perhaps a tactic that he used on Smith. The tire of O’Donnell’s car was hit by a bullet. It brought his car to a stop in a less tragic end.

Hagen kills career

Police brass apparently had their eye on Hagen throughout 1918.

On Saturday, August 11, the Chief of Police had a conversation with Hagen about his knowledge of a May 19 burglary. It seems the chief knew of Hagen’s involvement. He gave Hagen until Monday to tell all that he knew, including the culprits’ names, or the chief would fire him.

Previously, Hagen covered up his troubles with high-profile street policing. It wouldn’t work this time.

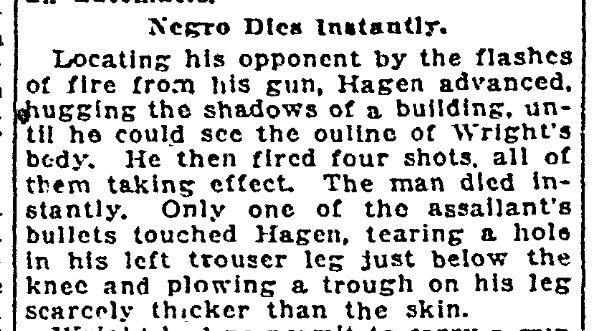

Early the next morning, Arthur Wright left his home for Sunday work as a longshoreman at the Great Northern docks. As he left his apartment at 14th and Main, he had a confrontation with Ed Hagen. We only know what Ed Hagen said happened, because Arthur Wright didn’t live to tell his side.

Ed Hagen shot Arthur Wright four times, one of them in the head. He claimed that Wright fired first, but it seems unlikely that Hagen could return fire from a distance, landing all four bullets, after being shot in the leg.

In a rare mention of Seattle’s Black community, the Post-Intelligencer commented that they had “severe [anger] against Hagen since… Frank Smith… was killed”. The community knew things were not as they seemed, and Hagen was to blame.

But it was Hagen’s role in the burglary of that shoemaker in May that ended his police career. He told the chief that he wouldn’t be a stool pigeon, and quit on Monday before he could be fired.

A city council member petitioned Mayor Ole Hanson to reinstate Hagen, but the mayor refused, knowing Hagen was dirty.

Ed Hagen’s downward spiral

With the weight of a policeman’s uniform lifted off his shoulders, Ed Hagen went wild.

In December, driving erratically, he struck a man getting out of a streetcar and sent him to the hospital. At the start of February 1919 his wife sued for abandonment because she and their children hadn’t seen him in days.

In April 1919 Hagen finally committed a crime that would put him in jail. He was arrested as part of a bootlegging ring that involved active police officer W. F. Patton, active sergeant Gus V. Hasselblad, former sergeant Fred Smart, former patrolman Dick Russell, and five others. They stole more than 1,700 bottles of liquor from the United States customs warehouse at Lenora and Western on the nights of March 29 and 30.

Mayor Ole Hanson gloated to the Seattle Times: “I wasn’t surprised to hear about the arrest of some of those fellows. I knew they’d get Ed Hagen, sooner or later.”

He appealed his case all the way to the Supreme Court, flush with cash to pay lawyers. He didn’t wait for the court’s ruling to get back to his “work” though, the same work that he supposedly chased down Frank Smith for.

Before Christmas, federal officers seized 737 quarts of beer from the Hagen home, along with a distillery, two five-gallon kegs of malt, two tubs, and one bottler. Hagen’s penalty was paltry, a simple fine of $800 after his guilty verdict. He paid it the same day.

Officers arrested Hagen again on New Year’s Eve in West Seattle for attempting to receive smuggled whiskey at Seola Beach. For two months police watched him receive liquor from small boats. But unable to stop the boat with the liquor aboard, they instead charged Hagen for carrying a concealed revolver. Hagen faced six months in the county jail after his guilty verdict this time, so he appealed. During the appeal he negotiated a plea deal, pleading guilty, and receiving a $150 fine.

Not even two weeks after the West Seattle incident, King County deputies arrested Hagen after a chase on Bothell Road, the predecessor to Lake City Way. They found gin, whiskey, and other liquor in his car. Hagen’s fine was $250 this time.

Ed Hagen finally goes to jail

Then on March 20 and 21, 1921, Ed Hagen had two course-correcting days. The Seattle Times shouted about him in a banner headline: “Former policeman goes to penitentiary; fist fight, auto wreck cap Hagen’s career”. March 20th, he was arrested. Police received a tip that he was picking up a load of King George IV whiskey from his wife at home. Police were late, though, and spotted him already leaving, coming towards them on Dearborn Street.

They stopped and signaled him to stop. Then Hagen tried to speed past them but instead hit the police at higher than 35 mph. Police officer Hunt who was getting out of the car was thrown but luckily unhurt. Another officer Anderson got out of the car and turned his gun on Hagen. Hunt began searching Hagen and Hagen punched him; Hunt punched back. A civilian stopped to help and got punched as well. Officer Hunt described the scene, “I hit him back in the face. He pulled his coat off and challenged us to take him. He said he would not be taken alive. He acted like a crazy man.” These cops showed more restraint than Hagen ever did.

Then, on the morning of March 21, he lost his appeal to the Supreme Court. The news convinced prosecutors to delay charges against Hagen from the previous day for whiskey and striking an officer, since he was already headed to the federal penitentiary.

The Town Crier, unfazed by the death of two Black men, wrote bemusedly about Hagen’s high-profile career of crime:

“And thereby Seattle for a time is deprived of one of its most spectacular and entertaining figures and those who take their amusement cynically of one of their choicest pleasures. Ed Hagen, the boucoup bootlegger. Never uninteresting was Ed, never tedious. The limelight descended on him as a halo. The pussyfoot was a step he never learned, as demonstrated by the fact that they got him when he tried it. No, everybody in town knew what Ed Hagen was doing, and plain citizens were prone to wonder how he got away with it. With his racy car and equally racy temperament, a dashing and spectacular figure.”

Town Crier, Mar 26, 1921

“I’m going to be a good dog over there,” Hagen said. Officials hoped he would serve his full two year sentence, but he planned on an early parole.

Six months in, Hagen’s lawyers cleared the way for his parole. He still had a six month county jail sentence hanging over his head, for carrying a concealed weapon at Seola Beach. Rather than wait for the appeal while in the federal prison, Hagen pled guilty and received a light $5 fine. The Seattle Times wrote that the “fine was lowest ever given in a liquor case in the United States court here”. Hagen said, “I’m through with booze.”

Hagen was freed after just under a year in prison, on March 11, 1922.

Ed Hagen not reformed

Perhaps Hagen was through with with booze. But the booze wasn’t through with him.

In November 1922, Hagen and his partner, Seattle police officer Edward Pielow, purchased the former Navy high-power speed launch Rubiyat, and began using it to smuggle booze from Canada.

The next year he wrote a letter to the P-I describing one of his first trips. Hagen tried to smuggle a load on his own despite not knowing how to pilot a boat. He purchased 26 cases of whiskey in BC and lost his way on the trip back in heavy seas during a windstorm. Hagen saw lights and thought he was in Seattle. But venturing out the next morning he saw that it was actually Bellingham. The next night, lights frightened Hagen, which he thought a Seattle-based Coast Guard ship. Actually, it was a lighthouse way out on the peninsula near Port Townsend. He dumped all of his liquor overboard. It was too late to recover the liquor after he discovered his mistake, so he returned to Seattle. Capping his bad luck, the boat caught fire after he docked it in Lake Union.

The episode on his Navy launch showed that Hagen was not particularly careful. Sometimes his operations failed, but he knew he the penalty would just be more fines, a small cost against his operations. Actually writing about it to a newspaper showed how little concern he had if people knew the truth.

It’s astonishing that his admission and other crimes did not violate terms of his parole. Seattle law seldom held Hagen accountable for his actions, and never for the worst of them.

Ed Hagen sentenced to McNeil Island again, but skates

Hagen and Pielow used whatever conveyance they could get their hands on. In mid-February 1923 Canadian customs agents stopped the pair, driving with lights off at night across the border into Canada. News accounts reported that the car was ready to be filled with liquor, but the Canadian patrol simply sent them back. They did inform their U.S. counterparts, though.

On February 21, federal agents raided Pielow’s “luxuriously furnished home at 122 Broadway”. They found bookkeeping accounts and notebooks of a massive liquor operation. They found cases of whiskey, Canadian beer, and a “large quantity of home brew”. Police arrested both Hagen and Pielow. And the department quickly fired officer Edward Pielow.

A week later, a raid caught Hagen’s wife at home with whiskey and beer.

Hagen and Pielow both faced charges of possession of alcohol and criminal conspiracy, and later that year juries found them guilty. They appealed and posted bail, free to continue smuggling alcohol in the interim.

In June 1924 Hagen crashed a car full of beer in Bellingham.

In November his pilot damaged their float plane in water near Victoria, B.C. Hagen concocted a ridiculous story about how they got so far from their written destination, Anacortes. It’s safe to assume they were there to get a load of liquor. Moorage for the float plane, a Boeing Model C, was at the Westlake Boat House alongside the Rubiyat.

The last of Hagen’s bootlegging arrest related news reports was filed on December 19, 1924. Federal agents raided his home and found moonshine.

While Hagen and Pielow appealed the conspiracy case, federal courts decided that warrants must have more evidence basis than just a police officer’s hearsay. It was common for local to police to simply tell federal agents that they had heard someone had alcohol, and then for a raid to occur. Using this as a new appeal, Hagen successfully overturned his charges. Despite their massive bootlegging operation, Hagen again went scot free. (Pielow became tangled up in charges against Roy Olmstead, and didn’t get off so easy.)

Ed Hagen back to baking; still conspiring?

After his 1922 parole from McNeil Island Penitentiary, Hagen opened Society Cleaners & Dyers, a clothes cleaning business at Pike and Bellevue on Capitol Hill. Considering that bootlegging was his primary profession in the 1920s, this business was likely a front. One piece of evidence in support of this idea is that his dye business closed immediately after Prohibition ended in 1930.

Unable to profit from bootlegging any longer, Hagen resumed his first career. Hagen again became a baker, working as a foreman for Lady Betty Bakeries in South Lake Union. After LBB closed in 1932, he moved to Langendorf Bakeries near Seattle University, where he headed their cake department.

While holding a normal job, maybe Hagen didn’t give up his successful enterprise of organized crime, though. Two stories give a glimpse into what that may have been.

In early 1931 Seattle police arrested Hagen as the force behind an attempt to blow up two bakeries. Prosecutors eventually dropped these charges. In 1936 police accused Hagen of being the mastermind of a series of burglaries of bakeries. That also never led to a trial. It’s unclear if police pigeon-holed him as one of the usual suspects. Or if he perhaps continued in extortion, racketeering, and occasional conspiracy to commit theft and destruction of property.

In 1936 Hagen was voted into the union office. Hagen became financial secretary for the Bakers and Confectioners’ Union Local No 9. He later became the union’s business manager, stretching into the late 1940s. It’s unclear if that was a full time position, but it’s what Hagen listed in the city directories, and what he was newsworthy for. After he lost an election for the first time, Hagen’s reported profession returned to Langendorf United Bakeries.

Edward Joseph Hagen died in August 1962 at 75 years of age. That meant that he outlived Frank Smith by 33 years, and Arthur Wright by 43. He was remembered by his family as a former boxing champion and a retired baker.

Further reading

- The story of Frank and Sadie Smith

- A tangential connection, bootlegger Roy Olmstead’s lawyer appears in the profile of United Grocers, part of Anderson to Mutual Markets

- Police corruption is discussed in my profile of Fred Trump

- Police corruption also comes up in the complete history of the Rainier-Grand Hotel

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.