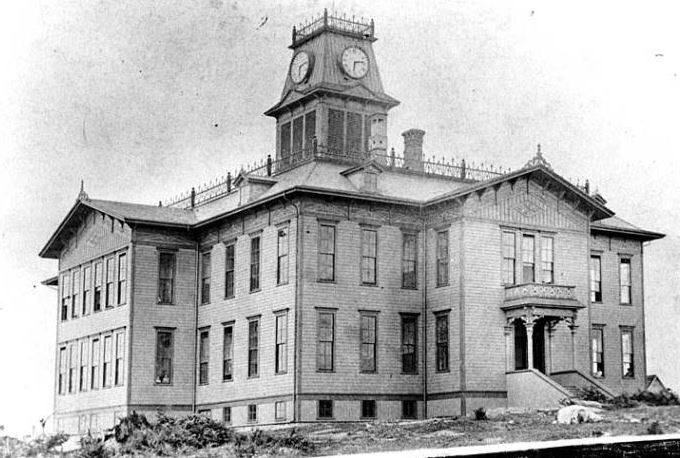

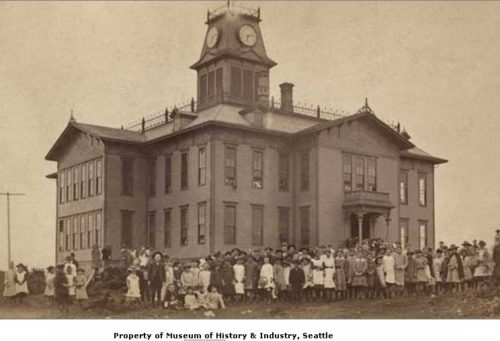

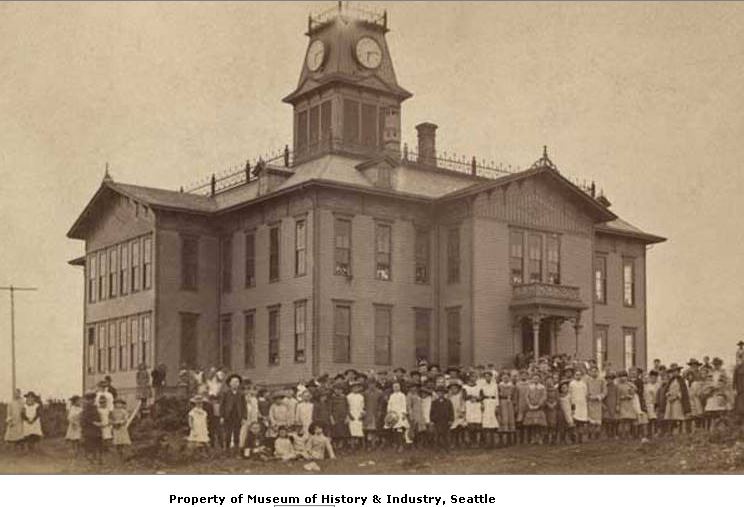

The clock tower of Seattle’s Central School stood in a commanding position.

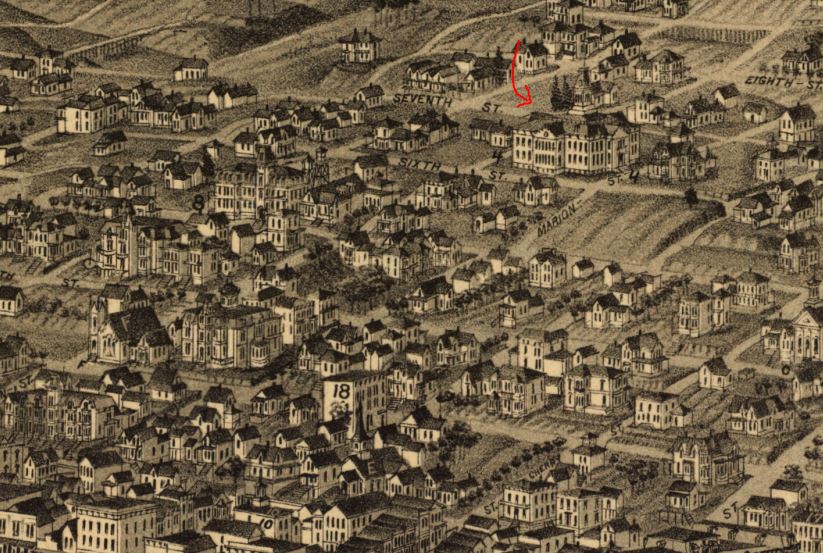

Built in 1883, the school was taller than any building around it at 6th Avenue and Madison Street. It stood on a knoll above the business district. People could see it from Lake Union to the southern wharves of Seattle… with a telescope even outside of Elliott Bay.

If lit, it would broadcast time for miles at night. If it rung a bell then valleys would carry the hours even father.

But the clock was missing more than that. It had no clockworks.

A New Central School

In 1882 architect Isaac A. Palmer submitted plans to the Seattle school board to build a grand new school for all students in the heart of the city. As the official Seattle school history says: “It was the first schoolhouse in Seattle with more than two classrooms. The elegant wooden building featured an imposing French mansard roof, clock tower, and tall central belfy.” (Built for Learning, Central II)

As Paul Middents and I have researched the history of Seattle’s clocks, this clock tower has really bothered him. Because although there is clearly a clock visible in the tower, Paul’s review of Seth Thomas and E. Howard tower clock sales has not revealed any purchase for Seattle in 1883.

Those two makers’ movements powered almost every clock tower in America. For Seattle’s clock to have a different manufacturer, or if it was purchased used, it would have a very out of the ordinary history.

(This school is sometimes referred to by its original name, the Sixth Street School. But architectural historians need to differentiate between different buildings. So this is also called Sixth Street School II, keeping it clear from the previous school on this site. And it’s sometimes called Central School II, because a prior Central School existed, the one down on Third Avenue.)

We Need a Clock

The school board’s budget apparently did not allow for the purchase of a clock.

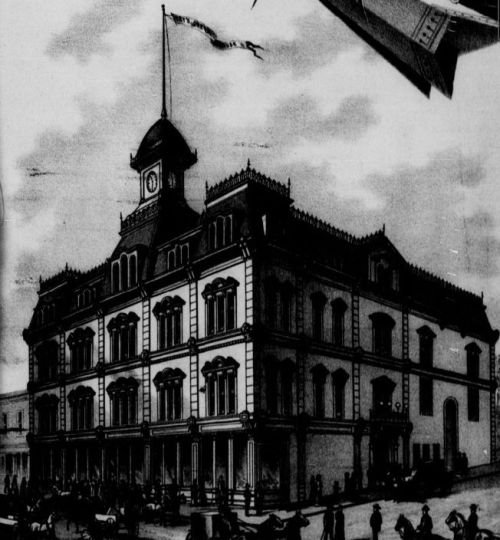

By 1884 citizens were restless for a clock. Construction of the new Opera House, the first large theater for the city, seemed to offer an opportunity.

“Nothing definite has been done in the matter of the town clock – but talk. A suitable clock would cost about $1500. Its dial would be quadrupled, having a face on each side of the lofty tower to surmount the Opera House. The clock would not represent the whole expense by any means, as the bell to accompany it would cost fully a thousand dollars, or more than twice as much as the clock. The proposition here is to put the clock so high that the face could be seen over the greatest part of the townsite, while the big bell could be heard over the whole town. It is proposed to have the tower lit at night, so that the hands can be seen distinctly at any time. A clock like this properly attended to would not cost more than twenty dollars a month, and would give our city a striking distinction over its sister towns, for whom it would set the time as well as for our own people. One man has offered to give one hundred dollars towards this worthy object, but the talk has not yet developed into tangible movement.” (May 13, 1884 Seattle P-I, p2 col 2, “Town Clock”)

In Response

An anonymous writer replied to the P-I editor’s call for a clock. The letter suggested that the Central School was a better location for the clock. This showed even if the school clock tower had a face with hands, no clockworks drove the hands or kept time.

“As you have placed the question of having a town clock before your readers, I suppose it is now open to the citizens of this place to express themselves as to the location of the same. In the item referred to, you speak of placing it upon a business block, located near the water front. You propose to pay $1000 for a bell to accompany said clock. Now the public schools of this city are without a bell to notify the pupils of the approach of the opening hours of school. Upon the central building is a lofty tower that already has the four dials and hands, and only needs the machinery to make the clock right all the time, instead of twice a day, as it is now.

“A large bell to ring out the school hours is an absolute necessity to secure regular attendance at school. There is certainly no need at all for another bell in the business part of the town. You have your two fire bells, which are quite sufficient for any extra occasion, and ring quite often enough to muster the firemen.

“But the location of a clock upon the central school house, possesses so many advantages over the Frye building, that an argument is not necessary to convince any one of the fact. The tower of the former building can be seen from all parts of the city and bay, including Lake Union and vicinity. I make the assertion without fear of contradiction, that a clock upon the Frye building could not be seen by one-fifth of the people that could see one on the central school house. Again, the Frye building is private property; if the public is to contribute towards buying a clock, let them place it upon a public edifice, so that it may be controlled by the public. Further, you propose paying somebody $20 per month for taking care of the clock. The school house has a janitor whose duty it is to stay in the building night and day. The duty of looking after a clock could be assigned to him without additional expense to any one. I have heard several citizens express themselves ready to contribute liberally towards placing a clock in the tower of the central school building, and have no doubt but the required amount, $2000 — estimated sufficient to buy clock and bell, by good authority — could be easily raised, if taken in hand by an energetic solicitor.

“– Tempus” (May 14, 1884 Seattle P-I, p1 col 3, “The Town Clock Question”)

Plea Redoubled

Seattle’s citizens did not rise to the moment. Neither the school nor the theater got a clock.

In March 1888 the Seattle P-I editors reminded the city of the need for a clock.

“Seattle needs a town clock. First, because of its utility; second, because all cities of any size have one; and third, because it is more or less of a public ornament. Some may incline to the belief that in these times of plenty, when a Waterbury watch goes with a suit of clothes, a town clock is a superfluity. Such is not the case; it is rather a necessity. A striking town clock with four faces, placed on some high tower in a central location, would be an addition that could not fail to be appreciated. One does not realize how much reliance is placed in one of these popular pieces of mechanism. That the public accustoms itself to consult them is well evidenced by the fact that, whenever by chance the clock gets out of order and the wheels stop, a loud complaining wail goes up from half the throats in the community. Let the city put up a town clock.” (March 18, 1888 Seattle P-I page 4 column 1, “A Town Clock”)

Too Late for School

The timing of the editorial tells us that the Central School never had a clock. A fire in the middle of the night destroyed the school three weeks after it ran.

The bell tolled for the Opera House just over a year later. The 1889 Great Seattle Fire consumed 120 acres of the city, including Frye’s theater.

Lending a Hand

Given the opportunity to rebuild the city in any fashion, architects and builders still did not add clocks to towers or facades on any of Seattle’s new buildings.

Instead it was up to Seattle’s jewelers to provide the public good of accurate time. In 1890 both Albert Hansen and J. K Basye purchased clocks from Seth Thomas and installed them at their stores near First and Columbia. They asked for permission to erect them on the sidewalk in public property, and the city council passed an ordinance granting it for each clock.

The first known publicly owned clock was on the facade of Denny Hall on the University of Washington campus, built in 1895. The first tower clock wasn’t installed until 1906, on King Street Station (then known as Union Station), paid for by the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads.

The King Street Station clock was an E. Howard movement. Perhaps taking advantage of their agent’s time in Seattle, Howard sold three street clocks in 1906 as well, to jewelers L. W. Suter, Albert Hansen, and Horace Hardy.

Howard street and tower clock sales remained strong after Seattle’s manufacturing jewelers Mayer Brothers became official sellers and installers. Known Howard installations by them include the new Colman Dock tower in 1908 and street clocks for jewelers Stacy Shown (1907), William Finck (1908), Samuel Friedlander (1908), Clement Coffin (1909) and Thomas Wolfe (1909).

The firm had a creative genius, Joseph Mayer. By 1911 Mayer had designed his first street clock case, using a Seth Thomas movement. More examples remain of Mayer cases with E. Howard movements. He went on to design his own line of street clocks, and his own movements. He built scores of street clocks, and many of them ended up in Seattle.

Due to Joseph Mayer Seattle went from spending all of the 1880s wishing for a single clock, to being known as the “City of Clocks” by 1930.

(The closing was updated based on Paul Middents’s comment below.)

More clock articles

- Where Seattle’s Street Clocks Were

- Street Clocks and Stacy Shown’s Showns

- Mayer Brothers in the Klondike

- Time to Daylight and Save Time in Seattle

- Time Travel to Pike’s Forest of Clocks

- Time Travel to West Seattle

- Seattle Street Clock Inventories, 1920s

- A Broadway clock that tells history, not time (on CHS)

- Blueprints of Seattle’s Clocks

- The original Seattle Clock Walk

- The City-Wide list on the clock walk site.

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I think the Northern Pacific purchased the King St. Station clock directly from E. Howard. We know Howard sent a young engineer out from their Chicago office to supervise the installation of the tower clock and clock system for the station. This probably helped inspire Joseph Mayer to get into the business.