At 12th Avenue and Pike Street, Capitol Hill’s former Auto Row Apartments was Seattle’s first apartment built, owned, and occupied by Black people.

It was built in 1905. That’s three years before the Woodson Apartments, described in this archive photo caption as “the first apartment building in the city for African American tenants”. Built by the same family, the Auto Row is almost forgotten. So, this article attempts to reconstruct some of the Auto Row Apartments history.

Beginning with the end

Developers demolished Auto Row Apartments in 2014 to construct the Beryl Apartments. Auto Row Apartments was at 1510 12th Ave, just north of a large and more noticeable Victorian (also replaced by the Beryl) on the northeast corner at East Pike Street.

At the time of demolition, and from at least 2007 according to Yelp reviews, Seattle Trading Post occupied the building’s northern retail. It was an affordable thrift store and used furniture seller. To the south, the second space was empty from at least Google’s first street view photo in 2007 until vintage boutique In Commune moved into it in December 2011.

Update 1/1/2022: My friend Tiffany remembers going to a party probably in the southern retail space in the 1990s.

Update 1/3/2022: Twitter use Marillyn shared this view of the interior of In Common in 2013.

2012 ~ In Commune pic.twitter.com/mJMutmbgUK

— MARILYN A BOYD (@MARILYNABOYD1) January 4, 2022

Fergie’s Cheesecake Plus

If you are a truly long-time resident of the neighborhood, you may remember earlier businesses.

Fergie’s Cheesecake Plus opened in January 1987 and closed in 1992 or 1993. Owned by Tony Ferguson, it was a wholesale cheesecake maker with a small storefront serving coffee with cheesecake here and in Pioneer Square. This location was his first. According to his autobiography Mr. Claib, Ms. May, & Tony, Ferguson decided to become a baker in 1986 and started by buying up used equipment.

In January 1992, the Seattle Times featured him in an article about the challenges for Black business owners. Esther Hall Mumford’s 1993 book Calabash, a driving tour of Black people’s history and culture in Seattle, also included Ferguson’s store as a stop. But Mumford stamped “CLOSED” over the text, warning readers away.

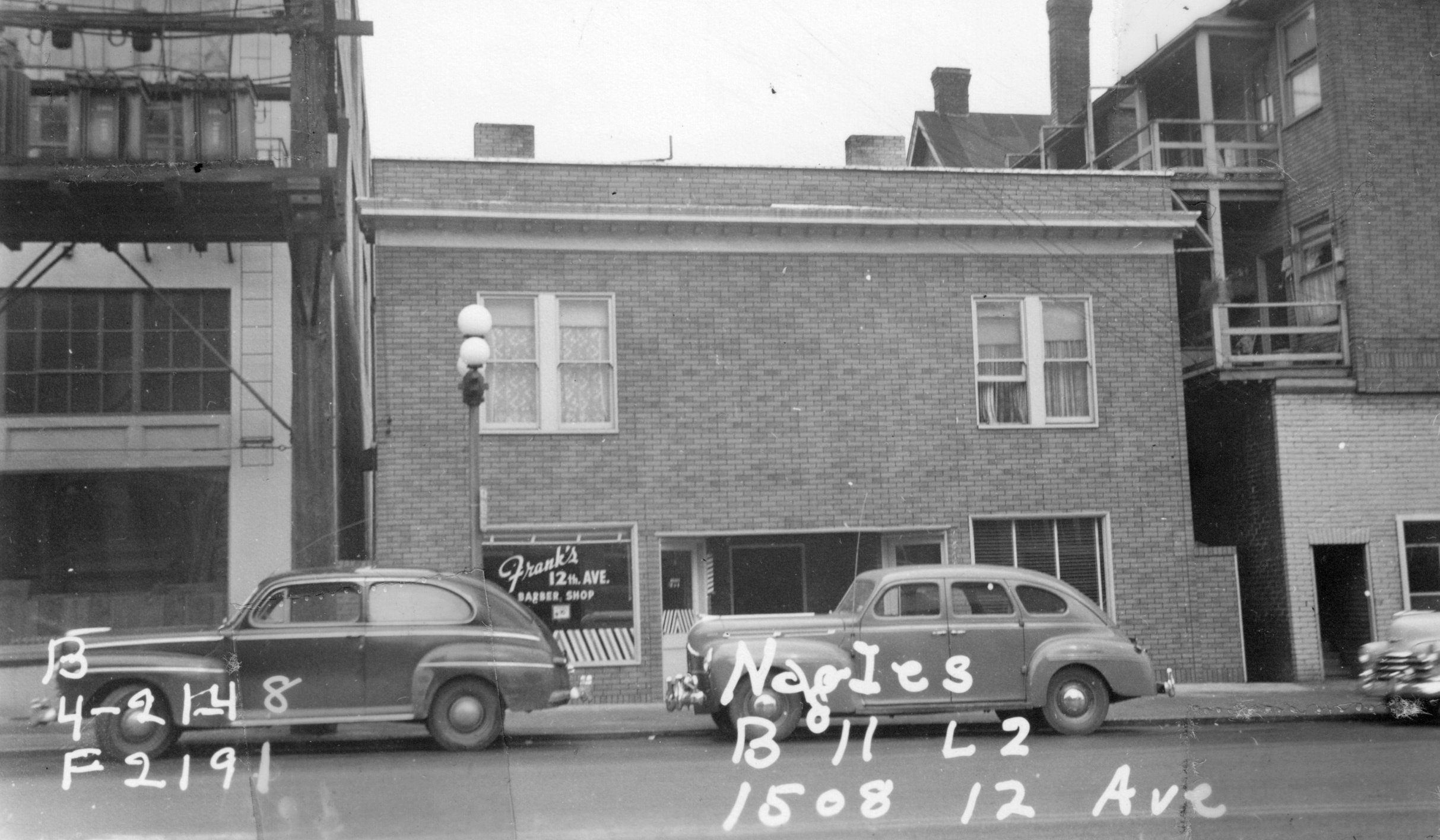

Frank’s barber shop

From 1947 until 1971 the retail space held Frank Swenson’s barbershop. Frank, son of Norwegian immigrants, and his wife Martha Ann lived in the back of the store. He lived there alone after she died in 1952 and for some time after he retired in 1971.

Frank earned a brief biography at the time of his retirement from 70-odd years of barbering. It included a frightening anecdote of an extreme case during his work as the children’s barber at Rhodes department store. Faced with a child that was too wild and reluctant for their first haircut, he resorted to tying them to the chair. Of course, he also cut children’s hair at his own store, and one not-quite-so-extreme case got a photo spread in the Seattle Times in 1950, below.

Mumford’s profile

When Mumford profiled Tony Ferguson’s business in 1993, she opened the door to the deeper history of Auto Row Apartments:

Most of the buildings erected by African Americans in King County were designed by master builders or carpenters rather than architects. One of the most accomplished builders was Robert Butler who came to Seattle in the 1890s. About 1905, he and another African American, a man named Tibbs, built this apartment building for Zacharias and Irene Woodson who moved from Chicago in 1897. Many African Americans found accommodations at this building upon arrival in Seattle during the early years of the century. In a 1909 Seattle Republican article, Butler was reported to have built more houses in Seattle than any other African American.

Mumford, Calabash, p 53

The remainder of this article explores Mumford’s profile of Auto Row Apartments bit by bit. However, some paths lead to dead ends for now.

The builders

Robert (R. W.) Butler and a Mr. Tibbs constructed Auto Row Apartments from an unknown design. Mumford implied that Butler and Tibbs were the designers, though. Mumford also mentioned one uncited 1909 article by the Caytons describing Butler as a prolific and trusted builder. Another profile appeared in 1902 stating his Seattle contracting career started by 1896:

“a well-known builder and contractor of this city and has been for the past six years or more, during all of that time has done a most excellent business. Mr. Butler has erected some of as handsome buildings in this city as have been erected by any contractor”.

January 3, 1902 Seattle Republican

No current profile of Butler is online or in publication.

In city directories, Butler listed himself as a carpenter, and the same is true for his 1913 death certificate. Advertisements in the Seattle Republican and Seattle P-I also billed him as a contractor. Butler and his wife Cornelia came to Seattle in 1889 from St. Louis. He started life in Texas in 1863, and her in Missouri in 1864, both likely as slaves. The Butlers were Democrats, perhaps the reason for sparse mentions of them in the Seattle Republican.

In 1894, they were two of the eight charter members of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, with Robert serving as its first secretary. Robert also conducted services until the first pastor was found.

Butler was an 1891 member of the Masonic Northern Light Lodge No 1 with William Grose and others, which apparently later became the Cornerstone Grand Lodge of the York Masons.

Tibbs’ identification hasn’t been confirmed. He may have been Clarence E. Tibbs, a contractor who appeared in city directories from about 1901 to 1910. Another possibility is the father of Sadie Smith, Blake Tipps, who sometimes wrote his name Tibbs.

The Auto Row Apartments owners

The apartment was built and owned for more than thirty years by the Woodson family. Zacharias (Z. L.) and Irene Woodson were property managers and owners. Specifically, the property for Auto Row Apartments was purchased in Irene’s name.

The February 20, 1905 Seattle Times reported on the construction permit filed by Irene for a “2-story frame flat building” to cost $3,000 at 1508-1510 12th.

The Woodsons lived downtown, where they leased space for a boarding house above the Olympic Livery stables at 5th and Pike. They rented rooms to Black tenants, part of the racially segregated system of boarding houses and rented rooms in Seattle. From there, they built several rental buildings for Black residents that appeared in the special Seattle Republican publication Northwest Negro Progress in 1907.

One of them was the subject building, Auto Row Apartments, originally named Woodson Flats. The Caytons described it,

“an excellent picture of the Woodson Flats of Seattle. This is by far the most complete and up-to-date flat owned by a Negro in the city. It is also the property of Z. L. Woodson.”

Northwest Negro Progress Number, page 46

Just after that, the Woodsons built the Woodson Apartments in 1908 at 1820 24th Avenue, a bit south of Madison and John. They also made the Woodson Apartments their residence.

After Irene’s death in 1924, building ownership of Auto Row Apartments passed to their son Fred Woodson. Coincidentally, Sadie Smith, profiled on this site early last year, was a signed witness on Fred’s marriage certificate to his wife Elizabeth in 1928. Woodson was a former amateur boxer and machinist who settled into a career managing the apartments his parents started.

Changes

It’s unclear when Woodson Flats’ name changed to Auto Row Apartments. It could have been as early as 1908 to avoid confusion with the Woodsons’ larger apartment on 24th. But the term “auto row” didn’t appear in the Seattle Times until 1912, so the change probably happened after that. One possible date is 1918, when the Woodsons leased the building to a boardinghouse mistress.

In 1910, city engineers flattened out 12th Avenue from John to Jackson. In front of Auto Row Apartments, that raised the street several feet, requiring the entrance to be raised as well. This change is visible in the photograph with the Victorian, taken in about 1912.

Ads showed the building available for lease or sale periodically from 1918 to 1928. In 1918 that effort was successful, leasing to white boardinghouse mistress Lizzie Stafford. The apartment changed from being a haven for Black residents to being yet another white-only rental building. The employment of residents switched from cooks and chauffeurs in 1917 to machinists and mechanics in 1918, earning the name Auto Row Apartments.

The building started as four suites, each with kitchenette, bath, closet and fireplace. The Woodsons divided them by 1918 into 15 rooms. In 1921 they advertised the rooms as 12 individual “housekeeping” rooms with six shared kitchenettes, four shared baths, four shared fireplaces, and five closets. In 1924 they called them clean, roomy apartments, with a piano, cozy fireplaces, and large back porches. By 1928 the Woodsons combined them back again to rent them as three-room apartments.

In 1937, King County took possession of the property to cover unpaid taxes, and the Woodsons’ ownership ended. C. Strickland purchased the property in 1948, the 13th Avenue Building Corporation in 1971, and the Payne family in 1986.

Early residents: police officer

For the first decade, when Auto Row Apartments was known as Woodson Flats, the renters were all Black people. They each deserve research and description, but here is an introduction.

John Samuel (J. S. or Sam) Peoples should have an article dedicated to him on a prominent site like HistoryLink or BlackPast.

Sam moved into the building in 1906, one of the first group of tenants. That January he was the second Black man to pass Seattle’s civil service exams, with the best grade and physical of his group. This qualified him to become the first Black patrol officer in Seattle Police Department history. After working Belltown briefly, his beat was Capitol Hill.

After a few months of service, the Seattle Times reported that some white officers refused to work with Peoples, in their words “through racial prejudice”. The white police officers filed frivolous complaints against him during his three month employment probation. In August, a neighbor accused him of helping to run a gambling club at 26th and Madison, but an investigation turned up nothing.

Per Cayton’s Weekly later, Peoples was “assigned to the Capitol Hill district, where he remained by petition of the residents of that section of the city, for many months”. The department promoted him to first class after a year.

In May 1908, the police chief dismissed Peoples from the force for “conduct unbecoming to an officer”, which Cayton referred to in 1919 as a “fix up”. Sergeant L. J. Stuart accused Peoples of something unreported in papers. Peoples appealed, but it was the end of his policing career.

He married late, at age 40. One of his children had a keen interest in local history, whose daughter, Carol Peoples-Procter, is a board member and past president of Black Heritage Society of Washington.

Residents: tamale baker

Another renter was Robert Powell, a cook. In the 1915 directory, Powell listed himself as a tamale manufacturer, living at Auto Row Apartments. He made the tamales at a shop at 6th and Pike.

His step-daughter Terseater Roberts and son-in-law Albert Slater lived with him at Auto Row Apartments. Terseater was a manicurist and hair dresser. Albert was a chauffer. Terseater divorced Albert Slater in 1916 and remarried Frank Cochran in 1917. Frank was a pastry chef, and perhaps similar professions made him close to his new father-in-law.

After leaving Auto Row Apartments, Robert Powell rented a home a block away, a few doors north of Mt. Zion Baptist Church at 1417 11th. It’s not clear on timing, but possibly Terseater lived with him in both places in between marriages. After her mariage with Frank she lived just north of Pine on 12th.

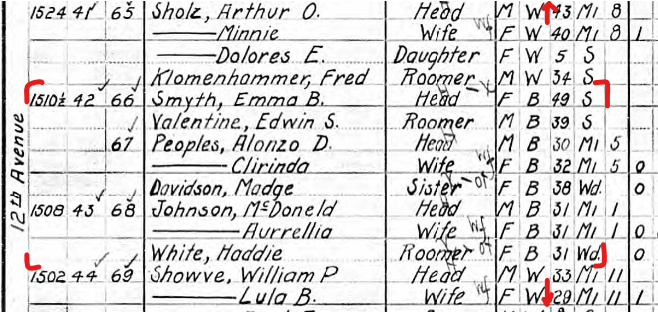

1910 census residents

The 1910 census shows eight Black residents in Auto Row Apartments. For instance, train porter Edwin Valentine, chauffeur Alonzo Peoples, concrete laborer McDoneld Johnson, Emma Smyth, formerly a hair dresser, and Haddie White who did work for families.

Alonzo was Sam Peoples’ older brother. Alonzo drove a car that he and Sam purchased together in 1907 while Sam was still in the police force. This turned into a “touring and sight seeing car” business for the two of them that continued successfully through at least 1930.

Reviewing the adjacent pages of the 1910 census, it’s clear that the area around 12th and Pike could not simply be called a Black neighborhood. Indeed, the vast majority of residents were white. However, with Mt. Zion Baptist Church at 11th and Union, and First African Methodist Episcopal Church at 14th and Pine, the area did have six other homes and apartments with Black residents like Auto Row Apartments.

Auto Row Apartments survived the automobile, but only one of the other 1910 buildings for Black people in the neighborhood did. The neighborhood streets were lifted for streetcars and autos in 1910, and the buildings replaced gradually for automobile sales and service by the mid 1920s.

As stated previously, the tenants of Auto Row Apartments were all white by 1920. Coupled with the demolition of other 1910 homes of Black residents, the first assumption might be that Black people left the neighborhood.

But that is not correct. There were still the two Black churches anchoring the neighborhood. In fact, a review of census district 207 (Pine, 14th, Madison, Broadway) shows that the number of Black people and number of locations both actually doubled from 1910 to 1920.

Remember its significance

When Seattle’s preservation officers surveyed Auto Row Apartments prior to demolition, no information about its history was available. The section of the survey on “significance” was simply blank.

The building looked weird ever since the lifting of 12th Avenue in 1910. Coupled with the retail alterations, the city Landmarks Preservation Board may have taken the position that it lacked integrity to carry its story. Indeed, city development managers may have approved demolition without even that close inspection.

In some sense, the significance of the building ended in 1918. After only 12 years, the Woodsons switched it from all-Black tenants to all-white tenants.

However, it’s important to remember the residential segregation of that time. Likewise, it’s important to know that Capitol Hill’s Pike/Pine neighborhood had Seattle’s first apartment for Black tenants. And that apartment was built just two years after Capitol Hill development began.

Further reading

- Seattle’s Black families’ homes in 1909

- Frank Smith and Sadie Tipps

- Black residences in Pike/Pine in 1910 and 1920

- Foster Miller wedding (on CHS), a story of contemporary racism

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.