Only one of Seattle’s drive-in markets is extant, the current Builders’ Hardware & Supply in Interbay. At its core, this article is an exploration of the historical context of that building.

The neighborhood grocery changed from a business type into a major industry in America during the early 1900s on the back of significant commercial innovations. Massive growth and consolidation of chains followed the introduction of self-service groceries in Los Angeles in 1914. LA continued inventing creative business processes with supermarkets in the late 1920s, but before that came a transitional commercial architecture: the drive-in public market.

Note: After you’re done, look through photos of the markets, or watch a video of me talking about them!

Drive-in Markets

Part super service station and part public market, drive-in markets were the first building type to interface with off-street parking in the way of a strip mall. They also resembled strip malls because of their lack of chain identity, and due to the number of independent vendors that leased space. But they were public markets, so sellers each represented one of the business types we are used to seeing at the Pike Place Market: meat, dairy, fruits, vegetables, seafood, groceries, baked goods and other food items. They were all in an open space with vendors shoulder to shoulder.

Typically the building was L-shaped with an anchor service in each end and parking enfolded. A kiosked gas pump refueled customers in the parking lot near the street, drawing motorists off of busy arterials. All drive-in public markets attracted customers with the closeness of parking and ease of loading parcels. Many of them also offered additional services like taking orders from your car window and delivering the goods to your trunk.

The first drive-in market was opened in Los Angeles in 1925, and within a few years the building type was proliferating that area and spreading to new cities. In his book on drive-in markets, Richard Longstreth said,

“By 1928, these facilities were being constructed in Los Angeles at the rate of about a dozen a month; three years later, more than two hundred would exist in southern California.” (The Drive-In…, page 32; see note at end of article)

Seattle built drive-in public markets in a short window from 1929 to 1934. That period began after the business model and architectural design had been proven in Los Angeles and ended due to economic pressures and changes of business models during the Great Depression. So far six Seattle drive-ins have been identified, only the first of which was completed before the stock market collapsed in 1929. Another planned market was scuttled immediately after the crash. It is possible that another handful will be discovered within the city limits, and presumably there were more around Puget Sound. I hope that local historians, architectural historians — and other people who love to understand how our built fabric became what it is — will share this article and help to unveil the full history of drive-in markets in our region.

That first building in Seattle was for Gerrish Brothers, and replaced their existing grocery store. It was also the only of the six which seemed to completely ignore what had been learned in LA, its architects sticking with a conventional building layout and parking interface. The other 5 markets were all typical of the bulk of drive-in markets: L-shaped, at or near important intersections on major arterials, and incorporating independent vendors, anchor tenants and gas kiosks.

Gerrish Brothers’ Drive-In Market

Seattle’s first drive-in market was opened in 1929, built for the Gerrish Brothers at 4th and Virginia by owner V. V. Tarbill. Brothers Charles and Arthur Gerrish relocated to Seattle in 1902, opening their first store in Green Lake. They expanded to several stores, but by the late 1920s had one store in Pinehurst. They moved their store to Belltown at 2408 4th Avenue in order to open a public market adjacent.

Gerrish Bros’ Drive-In Market was designed by prolific Seattle architect George W. Stoddard. It did not follow the L-shaped design that had become standard in LA at this point. Instead the building was set back 25 feet from the property line for off-street parking. Although not described in the September 1, 1929 article about the project, a neighboring lot was empty and may have been used as additional parking .

By the end of 1931 the Gerrish Brothers had succumbed to the Great Depression. An advertisement broke the news:

OLD established retail grocery, meat market and large fruit and vegetable stand; doing good cash business; we are retiring and will sell cheap and on terms. Apartment house neighborhood; low rent.” (October 16, 1931 Seattle Times)

Announcements like this litter American newspapers during the early 1930s, usually caused by financial problems. The economic impact on grocers big or small was severe. Perhaps that is what caused Gerrish Brothers to close. Within a few years Charles’ son Charles Jr started a market with Robert Garrison on Queen Anne Hill, later known as Quality Market.

(Plans for the market are on file with the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspection. I did not include them because they simply reveal a rectangular building.)

Westlake Drive-In Market

(Unbuilt)

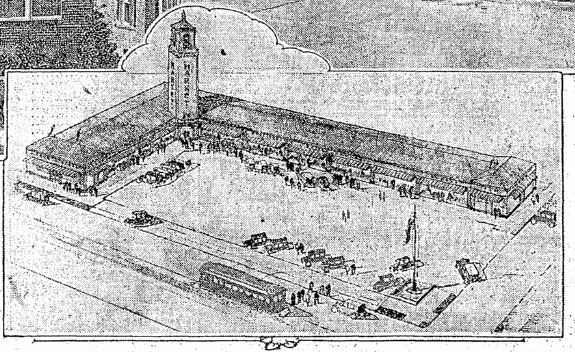

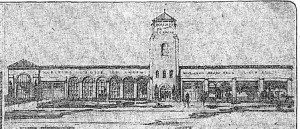

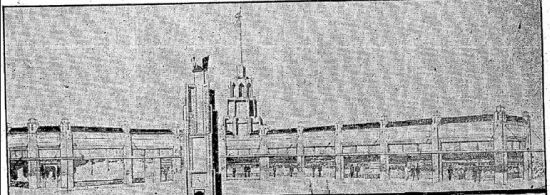

A late 1929 Seattle Times article announced that W. M. Widrig would form the Drive-In Market Corporation. With his brother J. S. Widrig and partner H. Nickerson, he planned to open 12 drive-in public markets within a year. First up was a facility at the northeast corner of Westlake and Mercer, L-shaped and graced with a large tower.

Widrig promoted the idea in the Seattle Times article by saying,

“The drive-in type of public market is extremely popular in Los Angeles and other California cities, and Seattle’s traffic conditions are such that we believe that our markets will be equally successful. They will enable house-wives — and men — to park their automobiles while shopping, and are to be built on arterial thoroughfares in various parts of the city.” (September 8, 1929 Seattle Times)

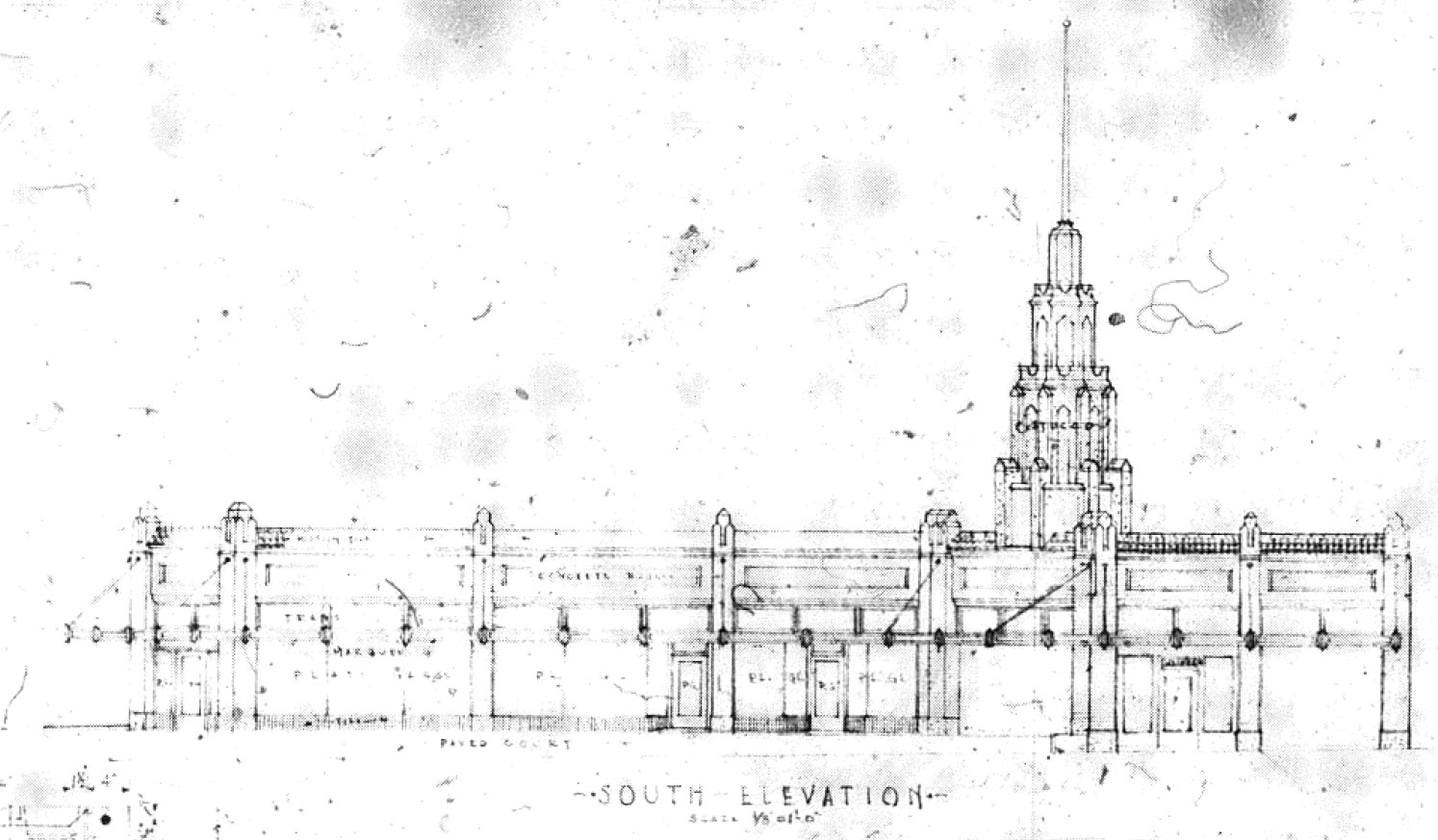

The article went on to describe the building design as having a flood-lit, 50-foot tower in an L joint of the building that would be topped with a beacon. The building would have tile-framed showcase windows for all of the ten market vendors. Perhaps influenced by the Spanish revival style of many of Los Angeles’ markets, the Westlake structure would be topped with colored tile and have stucco and art tile trim on its brick walls.

Aerial photographs from 1936 show a very different building. Parking for 10 or 12 cars was available in a small lot right at the corner. A tower rose from the center of the Westlake facade of a large, rectangular structure.

So what happened? Six weeks later the stock market crashed on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. The Widrigs must have needed cash immediately, because within three weeks the Seattle Times announced that Seattle’s biggest ice cream parlor chain, Horluck’s, would be building a factory there instead. Stories in the paper show that Horluck’s did in fact finish the factory, and architect renderings match the 1936 aerials.

Roosevelt Pay’n Takit

I have found few details on this building beyond a December 8, 1929 Seattle Times article, recounted here. In particular I don’t know what the drive-in was called.

It was built for Safeway’s Pay’n Takit grocery chain at the corner of 69th and Roosevelt Ave NE (then known as 10th Ave NE) by real estate developer West & Wheeler. They leased space to unidentified vendors in a 100 foot long section that formed the base of the L. The building was designed by Thompson & Thompson.

Motor-In Market

In 1930 the Motor-In Market opened at Queen Anne Avenue and Republican. Like the planners of the Westlake market, Barnum-Lemcke Investment Company optimistically formed Motor-In Markets, Inc. with the intention of building a score more. Likely because of the Great Depression’s impact on the finance market and general business conditions, they apparently did not continue building. However, it is also possible that they built facilities outside of the Seattle city limits, beyond the scope of this research.

H. W. Lemcke paid Los Angeles developer C. A. Henslee to create it for them. Local Seattle architects Hancock & Lockman were hired to draw up the plans, although it is not clear how much input they had on design beyond Henslee’s drive-in market template. Henslee appeared with architect H. C. Britt in a photograph of the groundbreaking. Britt may have been Henslee’s in-house architect, as his name appears in articles about other Henslee markets in Califorina.

A June 11, 1930 Seattle Times article claimed that Henslee had 66 drive-in markets in 1929, presumably all in LA. Later, an October 16, 1930 article said that Henslee had built 84 drive-in markets so far that year, almost all in LA with one in Oakland. To that point Henslee had built 150.

The Motor-In Market building survived until 1972 when it was demolished for construction of the Dick’s Drive-In Restaurant that remains on the site. This Dick’s is the favorite of Bill Gates.

Montlake Drive-In Public Market

The Montlake Drive-In opened on Friday, March 13, 1931, developed by ice cream magnate George Horluck on property that he owned. Two more were under planning. The architects were McClelland, Pinneh and Jones.

Announcements in the Seattle Times indicated that it was leased to the Producers’ Marketing Association, but surrounding ads featured Horluck’s ice cream shop. The Montlake Floral Company and Feht meat shop were the only other names included, despite ads for a variety of products.

In July Horluck sold the building to W. H. Hohag. There are no indications that Horluck or the Producer’s Association continued their plans for building more drive-in markets.

Cove Mid-City Market

(Only extant structure)

This is the building that started my investigation into drive-in markets. Currently it is Builders’ Hardware & Supply. Their website has a thorough corporate history, which describes how by the early 1940s Carleton Hardware was at 1516 15th Ave W. This was purchased by a firm called Washington Hardware, and in the late 1940s Carleton was renamed Northwest Builders Hardware & Supply, and it continues to this day.

But that building started as a drive-in public market in 1931, the Cove Mid-City Market, which continued until about 1938. I was led to it while indexing the locations of its anchor tenant and writing about Seattle’s Piggly Wiggly stores. By this point Piggly Wiggly was owned by Safeway, like the Pay ‘n Takit that opened in the drive-in market on Roosevelt.

I was amazed though to learn about the building’s architects, Welton Becket and Walter Wurdeman. Wurdeman & Becket went into practice together until Wurdeman’s death in 1949. Then Becket’s firm went on to lead the design of Modern Los Angeles.

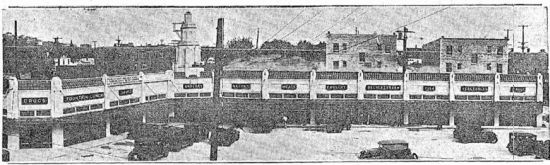

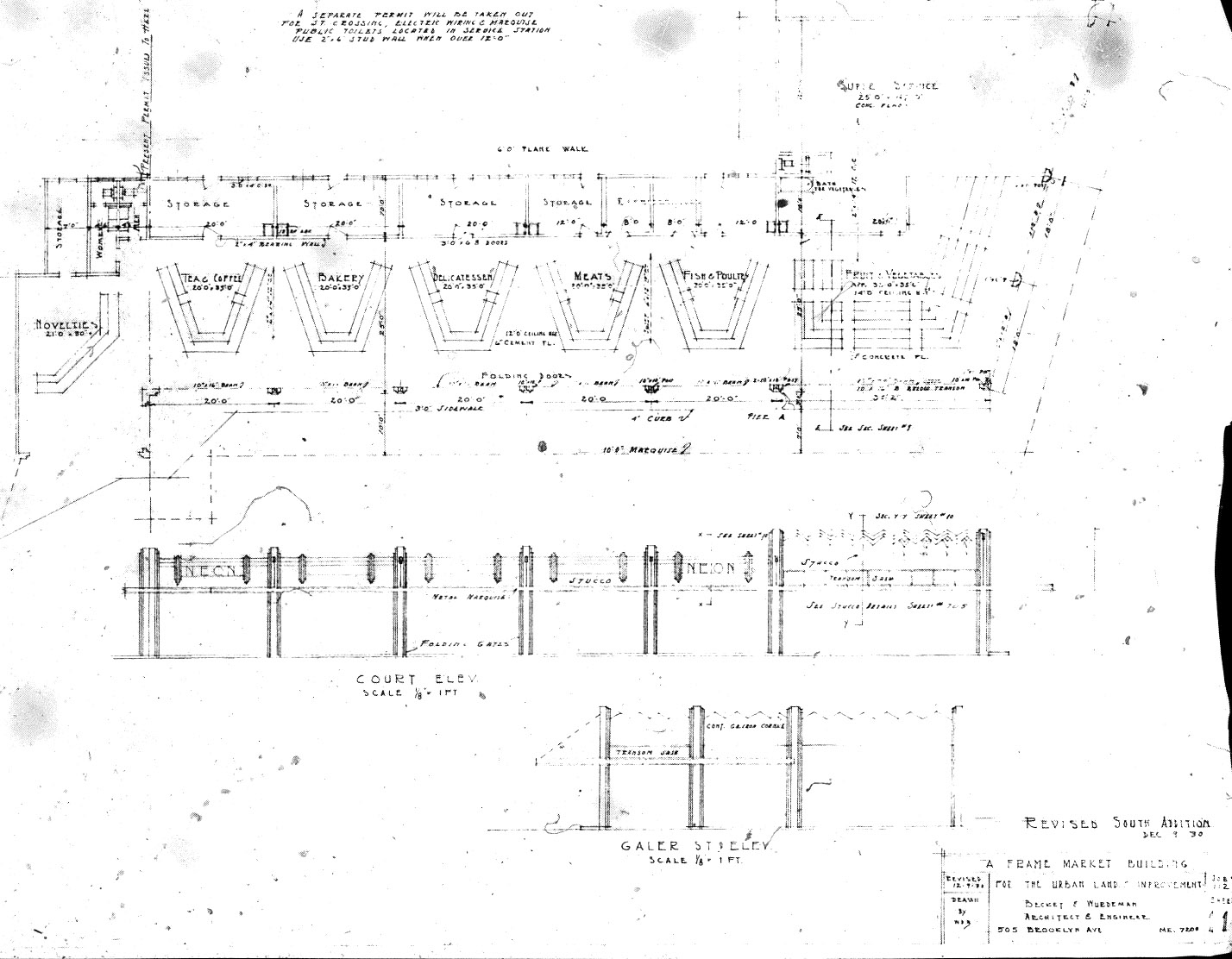

Let’s get back to the basics of the market, though. Many details were covered in a full page article/advertisement in the March 26, 1931 Seattle Times.

On opening day the first lessees were:

- Piggly Wiggly, groceries

- Helen Lea, restaurant

- Bartell Drug Company

- Van de Camp’s Holland Dutch Bakery

- Van Nostrand, butter, eggs, and dairy

- Hans Arp, fresh and cured meats

- Jame de Stephano, fruits and vegetables

- Shain Brothers, poultry. Their second store in the city, supplied from their own ranch.

- Langlouis’, doughnuts

- Monaster Fruit Company, fresh fruits

- Lee Wood’s Super Service Station, gas, oil, tires and accessories. 5th store in the city.

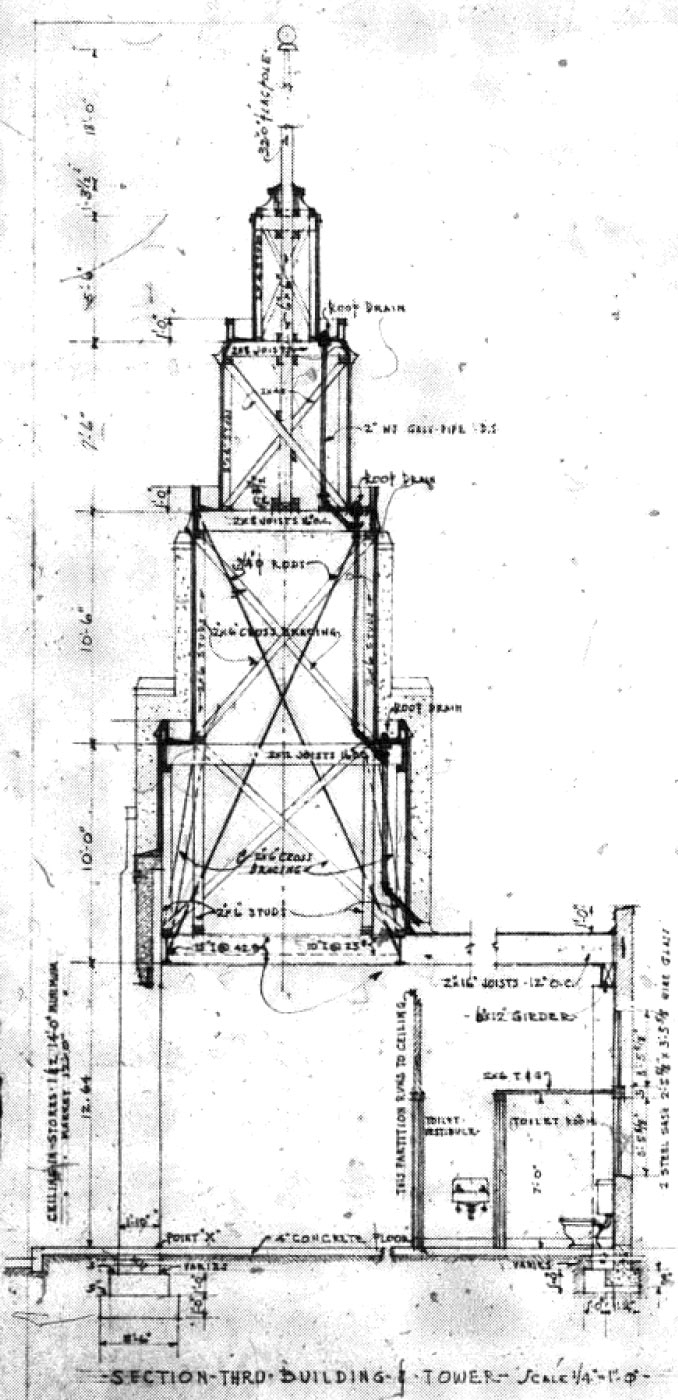

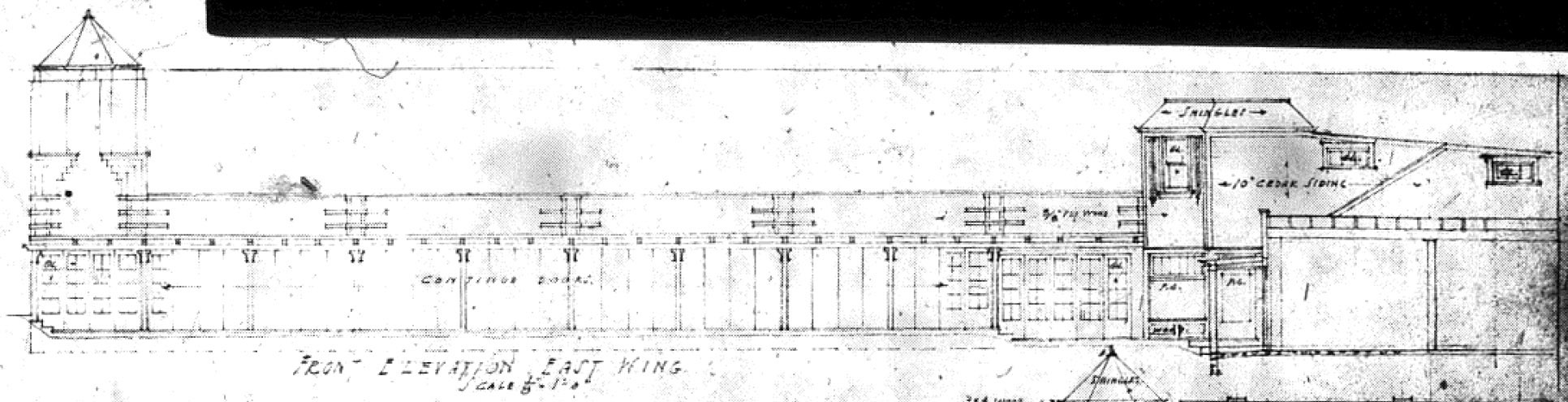

It was constructed by the Urban Land & Improvement Company, which owned 13 other smaller commercial buildings in Seattle. Becket and Wurdeman designed it with an exterior covered in stucco, lit by flood lights at night. The building originally had a tower at the junction of the L, perhaps lost after the 1949 earthquake. Plans for the market are in the collection of Becket plans at the Getty Research Institute, in Flatfile 5 described as “West Side Drive-In Market (Job 113, Seattle)”, but I have not yet seen them.

A short segment in the Seattle Times article declared that Becket and Wurdeman had “made a special study of drive-in markets and in the designing of the new structure they incorporated all the ideas gained from extensive research.”

I think it’s important to consider how early this building was in Becket and Wurdeman’s careers, and to pose the question about whether this building is what drew them to Los Angeles. For both Wurdeman and Becket their biographies from 1927 to 1933 are incomplete and equally credible sources contradict each other. What I have written is my best attempt to sort it out.

Becket graduated from the University of Washington in June 1927, the same class as Paul Thiry. Thiry of course is remembered as the father of Pacific Northwest modernism. After graduation the two of them then traveled to Europe, studying in France and then seeing the architectural wonders. Sketches and watercolors from their trip were displayed for a time at the Henry Gallery.

His Wikipedia page says Wurdeman graduated from the UW in the same class with Becket and Thiry. Confusingly though, Becket’s Getty profile does not specifically mention graduation from the UW but says that Wurdeman went to Fontainebleau before Becket’s June 1927 trip, and graduated with a master’s from MIT in 1928. While Becket and Thiry went to Europe, Wurdeman took a position with the major Seattle architectural firm Bebb and Gould, working on the plans for the Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park. Carl Gould was dean of the architecture program of the UW, so Wurdeman must have been a talented student to work with him after graduating.

In 1930 Becket passed the state architect exam and entered practice with Walter Wurdeman. Although both had worked at architects’ offices after graduation, the Cove Mid-City Market was within the first year of self-employment at least for Becket. The Seattle Times announced two projects by Becket designed in 1930: the Cove Mid-City Market announced in October; and the garage for the Meany Hotel which was announced in December. His profile at the Washington State Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation includes several homes and a candy shop remodel as well in 1930.

The Getty archives list several more projects completed in 1931, but then only one for 1932. Due to the Great Depression, by 1933 Becket and Wurdeman were unable to find work in Seattle. They chose to move their practice to Los Angeles.

I have not found a complete biography of Becket online, and I am searching for one offline. The biography that accompanies his archival collection at Getty states that he worked as a draftsman for C. Waldo Powers in Los Angeles in 1929. The Getty profile implies that Wurdeman was in contact with LA architect Charles Plummer around 1928, and states that it was Plummer that asked him and then Becket as well to move to LA and join him in practice. A 2012 thesis by Elise King frames the Plummer connection in reverse order though — Becket and Wurdeman moved to LA and then asked Plummer to join them. Which is it?

The Powers and Plummer connections should explain how they were able to so quickly survey drive-in public markets. If the Getty profile is accurate, Plummer’s interest in them certainly seems to explain the move to LA in 1933.

If that is true, it will be disappointing that we cannot string a chain of events that led to LA that started with the design of Cove. Even if that is the case though, the building is the physical embodiment of the two architects’ early connection to Los Angeles.

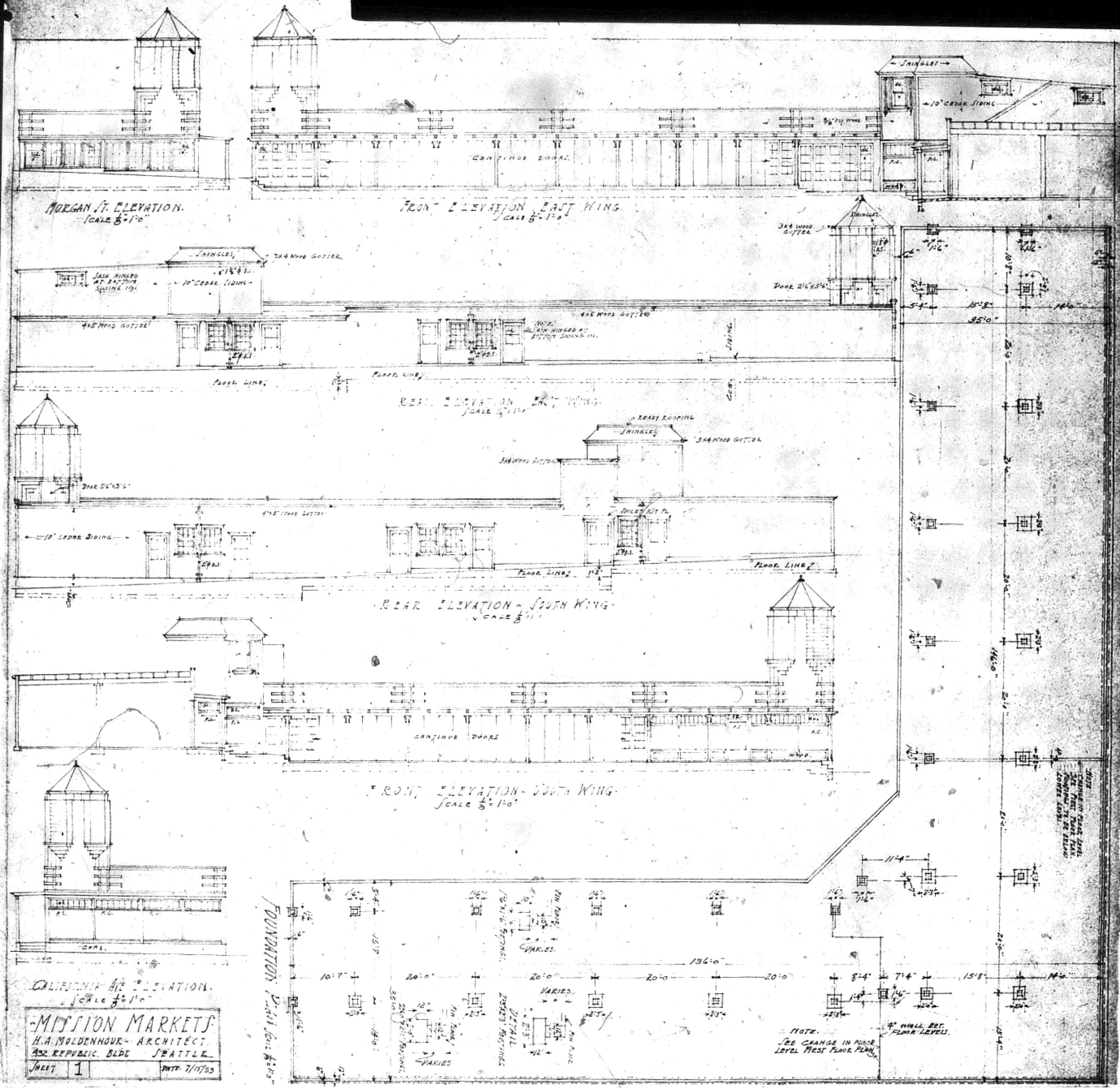

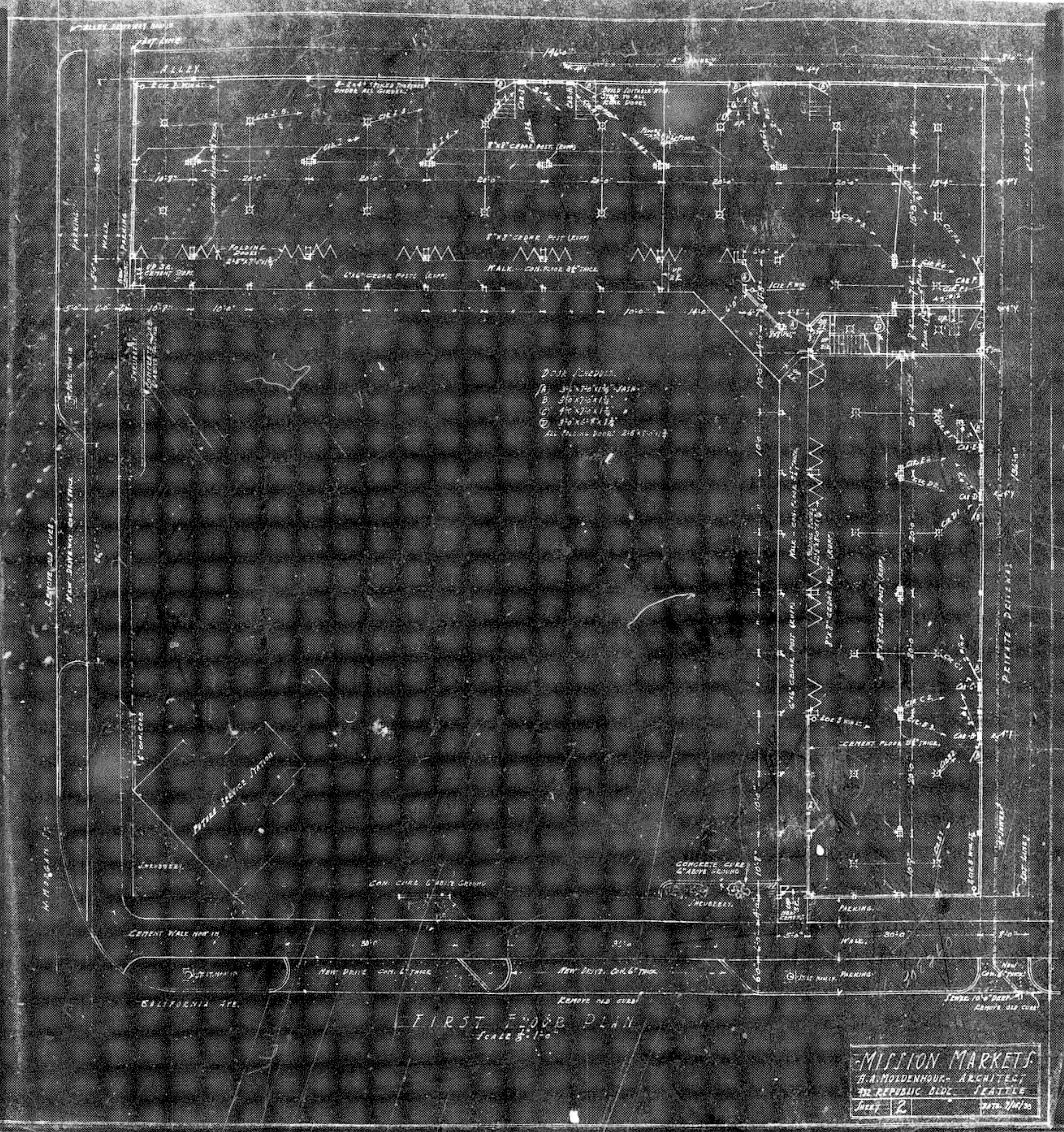

Morgan Street Drive-In Market

The last known market built was the Morgan Street Drive-In Market. It opened in 1934 at the intersection of Morgan Street, California Avenue, and Fauntleroy Way. On architect H. A Moldenhour’s blueprints the name Mission Markets was used, perhaps referring to the California origin of the type or maybe a reference to the building style.

An article promoted all of the businesses, a unique look at the makeup of one of Seattle’s drive-in public markets:

“J. N. Raybould will operate Morgan St. Meat Market – making this his second meat shop in West Seattle. A. F. Whiteley will operate a fully stocked grocery store under the name of Whiteley Red & White Grocery. Eli Calderon is installing the fruit and vegetable department.

“Hewetts will conduct the poultry and dairy department featuring Hewett Alderwood Manor farm products. Henry Eriandsen, the Magic cleaners of West Seattle, will maintain the cleaning department. E. P. Kelly, operating the rough weather service station, featuring Shell products.” (March 8, 1934 Seattle Times)

By the time it was finished the Mission influence was completely gone. It featured an octagonal tower and “partial English design”.

In Closing

Drive-in markets were short-lived as a building type, and the few built in Seattle did not last long as public markets. The trend in the industry was consolidation. Grocery chains merged and shed the least profitable stores. They also expanded their portfolios, broadening to cover all of the product types of a public market. These new groceries were known as super markets. They proliferated faster and further than drive-in public markets, incorporating all of the services and even off-street parking. Perhaps Seattle’s first was a 5000 square-foot Safeway super market in June 1937 on the base of Queen Anne. Other chains jumped in quickly. A&P (Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company) had three super markets in Seattle by May 1938.

Although it was only a public market for six years, the Cove Mid-City Market is Seattle’s last remaining drive-in market building. Hopefully Builders’ Hardware continues seeing value in the structure and carries it forward another 90 years.

Notes

I would never have understood the context of drive-in markets without Richard Longstreth’s book “The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914-1941“. It is fantastic and you must read it if you enjoyed this article at all. To test the waters, try reading Ryan Reft’s article Retail California, which is a nice summary of the book.

This article includes snippets of 1936 aerial photography which are available as a base map layer in King County’s iMap. Architectural plans are included for several of the properties, found at the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspection’s (formerly DPD) Microfilm Library. I have hosted these on Flickr at high resolution. Newspaper clippings are from the digitized Seattle Times archive. I have purchased scans of assessor’s photos of the markets, and posted them in a separate article.

More Groceries

I gave a talk on the Morgan Street Drive-In Market on March 20, 2016 at the High Point library for the Southwest Historical Society. You can watch it here.

Also don’t miss photos of the markets that I paid to have scanned by the state archives.

I have a growing portfolio of writing about the history of Seattle groceries. The center point is an AIA award winning supermarket in Burien. Here are the links:

- Seattle’s earliest car architecture in pictures – Drive-in markets

- Every Drive-in Public Market Ever

- Ice cream, beer, and the Montlake Drive-in Public Market (on CHS blog)

- Augustine & Kyer

- Charles Louch Farm

- Groceteria

- (Witness Weeps) – The Tragedy of Alvin Monson

- Piggly Wiggly Seattle

- Anderson, United and Mutual Markets

- Eba’s Cut Rate Markets

- Main Arcade Eba’s Store No 1

- Corner Market Eba’s Store No 2

- Wallingford Eba’s Store No 7

- Buy your rubber at City Market (on CHS blog)

- 50s Futurism Forgotten – The Burien Tradewell Story

- Capitol Hill – fancy groceries since 1923 (on CHS blog)

- A Broadway clock that tells history not time – Queen City Grocery and IGA (on CHS blog)

- Broadway Market v1.0 (on CHS blog)

- Blueprints of Broadway Market

- Piggly Wiggly on Broadway (on CHS blog)

- A shop on 11th Ave – Salle Brothers and Arai Grocery (on CHS blog)

Discover more from ba-kground

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi- my grandparents ran a small grocery and gas station on 15th North south of Northgate. I think I have a photo or two of it if you would be interested in it.

Old time grocery with living above and behind but legend in the family is it was the first Shell gas station. NOt so sure that can be true. It is now a hearing and speech clinic. Took my mom there years ago when she was still mobile.

Robin, I would love to see them. Can you email them to rob.ketcherside@gmail.com ? If you know the address or have other stories I would enjoy hearing them as well.