Frank Smith represented the opportunity for Black people in Seattle at the start of the 1900s. He and his wife Sadie built their own home, lived at a downtown club, and started their own business. But his death at the hands of crooked cops showed how the city being “not racist” was not good enough.

The Smith house described in print

This article is about husband and wife Frank and Sadie Smith. But it originated as the investigation of a photo of a house.

The house was one of thirty-three in Seattle featured in Northwest Negro Progress Number. That was a special edition of the Seattle Republican newspaper, published as a promotional push in advance of the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exhibition in Seattle in 1909.

The pamphlet cried out “Come West Black Man”, and it packed 80 pages with examples of successful Black men and women along with details about Seattle and the Northwest. For a more in depth look at it, read the article Seattle’s Black families’ homes in 1909 on this site.

Frank and Sadie Smith’s house was a simple design: one story with a basement. It was on a slope, possibly allowing a basement door or larger windows in back. There were two chimneys, one forward for a living room fireplace and the other in rear at the kitchen. The photograph showed a different pitch to the roof on the back of the house. Maybe this was an addition built shortly after original construction. That would also explain the square appearance it had in the 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Seattle, in contrast with the rectangular shape in the photo.

Horace and Susie Revels Cayton, the publishers of the pamphlet and the Seattle Republican newspaper, first described the Smith home in 1903 while it was still under construction. “Mr. Frank Smith has about completed one of the neatest homes that has been erected in this city by an Afro-American. Mr. Smith is a most trustworthy and reliable man, and those for whom he does business are always well pleased with his work.” After the Smiths completed it the Caytons wrote, “Frank Smith bought a lot on Nineteenth avenue and within the past year has built a neat cottage thereon and is now living under his own vine and fig tree.”

Later, the Caytons described the Smith home as “neat and well finished” in NNPN in 1907. This matched their overall assessment of homes of Black families in Seattle: few were large, but “all of them have pleasant homes and they are for the most part well cared for”. (Seattle Republican, 10/2/1908 page 8)

The photographs in the special edition were reprinted in the Seattle Republican off and on throughout 1908 and 1909. In October 1908 the Smiths’ house ran with a new caption. “Owned by Frank Smith, steward of one of the many clubs of the city. While he has done little toward beautifying his home as yet, it is due to the fact that he and his wife have quarters at the club and their home is rented.”

The Smith house located

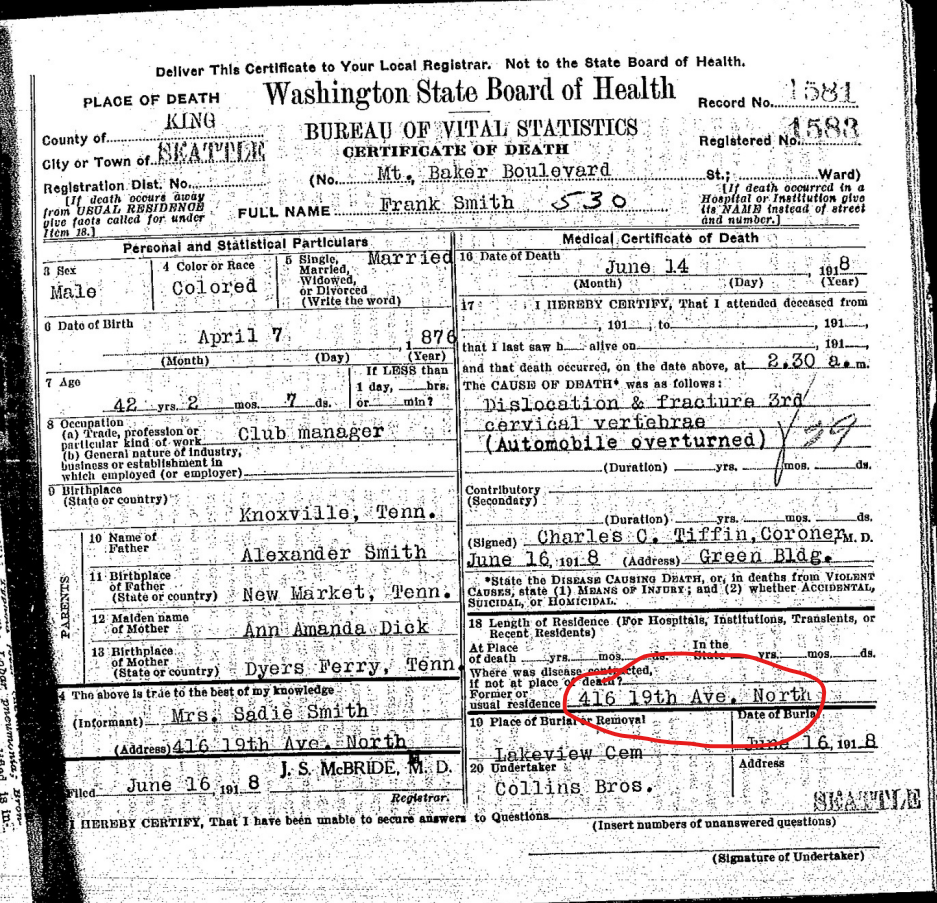

With Frank’s very common name, it took some digging and a partially assembled biography before the location of the house first appeared with confidence. Although captions of some photos of homes in the 1907 publication included a hint about their locations, there was nothing of the sort for Frank and Sadie Smith’s house. Finally Frank’s death certificate gave an address for the house: 416 19th Avenue East.

Today Madison Street is seen as a dividing line between Capitol Hill and the Central District. Given Capitol Hill’s history of racial covenants and the predominance of white residents early on, it could now be surprising to find the Smiths’ address north of Madison Street.

But the covenants came decades later, and Seattle’s contemporary Black community had its center point at 23rd and Madison, not its boundary. The FAME Church at Madison’s intersection with Pike and 14th formed another nearby hub that included the first church building for Mt. Zion Baptist Church and the Auto Row Apartments.

The Smiths were about six blocks northwest of the community nexus at 23rd. The Caytons’ home, also in the current Capitol Hill neighborhood, was another six west of the Smiths, and about equidistant between FAME and 23rd.

The first of James Moore’s Capitol Hill lots, eponymous to the later neighborhood, went on sale in 1901. A year later, Division Number 2 opened. Division 2 stretched southeast to the corner of 19th and Roy. In 1903 the Smiths built their home just two blocks away from that corner.

Replacements

The Smiths’ house no longer exists, but Google’s street view camera captured it as recently as 2011. A later owner enclosed the porch, and gave it a narrower set of front steps. A fence provided privacy on the side yard from the slope to Miller Park. The house seemed in good condition and still well cared for, 108 years later.

The house was built on lot 4 of block 1 of Francis A. Bell’s addition. Francis Bell arrived in Seattle in 1887 and was apparently not related to the pioneer Bell family. He filed the plat while single in 1891, and started selling lots as a husband and a father in about 1900. Most of this addition, which spans 19th to 21st between Republican and Henderson, is now part of Miller Park or Meany Middle School. Presumably the Smiths bought the house’s lot directly from Bell.

But the Smiths’ house was demolished in about 2014 and replaced by a new house and four townhouses. This sort of in-fill development is now common across the city and happening on every block in this area, particularly south of Madison Street. Getting five units on one lot is a bit more than usual, though.

Frank Smith and Sadie Tipps come to Seattle

Some important facts about Frank and Sadie Smith are lost to time, including how they met and how they came to Seattle. Once here though, they did leave a trail in records, news reports, and society pages.

Frank Smith was born in 1876 and grew up in Tennessee and Indiana, one of at least seven children of Alexander Smith and Ann Amanda Dyer. It appears that his oldest sibling Margaret married Charles Claige, now remembered in the Cleage family tree. So far no other family connections have been established.

Sadie was born Sadie Tipps in 1879. She was daughter of Blake Tipps (or Tipp or Tibbs) and Louise Bonner. Sadie was born and raised in Texas. The name Sadie is now popular in its own right, but Sadie is a nickname for Sarah. Sadie Tipps was indeed actually a Sarah and went by that name later in life.

Both Sadie and Frank were born in the same states as their parents. Assuming Sadie came from eastern Texas, then they were both children of former slaves. They were the first generation of their families born free to pursue their own life and own happiness.

The first we know of Frank Smith and Sadie Tipps in Seattle is their wedding day: April 13th, 1902. Soon after that, the Polk city directory listed Frank and Sadie living with her father, Blake Tipps, at 25th and Madison.

Blake did unspecified labor work according to the directory. He could be the “Mr. Tibbs” mentioned partnering with contractor Robert Butler in 1901. If so, he helped to build Auto Row Apartments. But that would mean he preceded Frank and Sadie’s move to Seattle, and there was a contractor Clarence Tibbs in Seattle in 1901 who is another candidate.

Frank was a waiter at the Rainier-Grand Hotel. The Rainier-Grand Hotel was the nicest of the hotels on First Avenue that catered directly to the waterfront. The Smiths came to Seattle during the gold rush era, in the afterglow of the 1897 Klondike gold rush and the 1900 Nome gold rush.

Prospectors who hit it rich arrived in Seattle on a boat or ship in Seattle’s harbor, looking for a place to stay. The Rainier-Grand was waiting for them. A recent article on this site chronicles the full history of the Rainier-Grand, and includes more about Frank’s coworkers.

Grand Jury charges Frank Smith with perjury

Frank’s work serving Seattle’s tourist and upper class at the Rainier-Grand apparently required him to keep confidence about illicit activities that went on behind closed doors.

This was put to the test in January 1903 during a grand jury investigation of an alleged private gambling room at the Rainier-Grand Hotel. The grand jury called on Frank to testify about what he saw as he served drinks around the hotel.

In April 1903 the grand jury found him guilty of perjury. They didn’t believe him when he said that he knew nothing of the gambling, didn’t recognize games being played (faro and roulette), and that he himself had never gambled.

“To add strength to his story he added that he had never gambled in his life, and consequently could not tell when others were gambling. Smith’s innocence was too much for the jury, so they ordered him indicted for perjury, averring that every one of the statements made by him were false.”

Seattle Times, Dec 31, 1904

That quote from the Caytons about Frank being a “trustworthy and reliable man, and those for whom he does business are always well pleased with his work” surely was in reference to Frank’s grand jury troubles. The Caytons said that in September 1903, while he was still under indictment.

Frank never faced any real charges. The investigation spiraled to include indictments against even the mayor and chief of police, but all of the cases were dismissed by King County Prosecuting Attorney William T. Scott, one by one. In December 1904 the case against his boss, hotel owner Horace Dunbar, was dropped as well. In a surprising turn of events, the witness refused to travel from Ohio to Seattle to testify. Frank Smith’s perjury indictment was finally dismissed later that month, too. The indictment hung over him for almost two years, though.

Moving to the home at 416 19th Ave E

In the midst of his surprising grand jury indictment, Frank and Sadie moved into their new home. It was complete in late 1903 or early 1904. They moved in to 416 19th Ave E. with Sadie’s father Blake Tipps.

Frank was a founding member of Trinity Lodge, the first Masonic lodge in Seattle for Black men in November 1903. The Smiths were members of Mt. Zion Baptist Church as well. Frank organized a church choir, and was a member of the church’s Evergreen Literary Society.

Along with community group involvement, the Smiths attended or hosted many parties and events mentioned in the Seattle Republican. From those, we know that they were friends with the Gaytons, Woodsons, Caytons, and other leaders of Seattle’s Black community.

The family of Frank, Sadie and Blake lived together for just a few years. In 1906 Blake died of appendicitis. In fact, Blake may have been living there alone while Frank and Sadie stayed at the Concordia Club.

Life at the Concordia Club

Frank left the Rainier-Grand Hotel after his indictment, and worked for a time at the Marquette Saloon at 2nd and Spring. He worked there at least in 1904. Later the Marquette was mentioned as a saloon with primarily Black clientele, and presumably that was true when Frank worked there.

After the Marquette club, Frank Smith found work as the resident steward of the Concordia Club.

The Concordia Club was a Jewish gentlemen’s club that started in 1903 and continued into the 1920s. From 1903 to 1905 it was located at Summit Ave and Union St. On April 12, 1905 it opened in the the Hoge Building‘s top floor, at Second and Cherry. The club completely remodeled the former quarters of the Seattle P-I with a ballroom, three card or dining rooms, a “women’s reception room”, a complete kitchen, and steward’s residence.

Frank and Sadie were likely there at the Concordia in the Hoge Building on opening night, already moved into the residence.

In NNPN, the Caytons described Frank’s job at Concordia as “a very lucrative position.” It was doubly so, because the Smiths were able to rent out their home while they lived at the club. And living at the club opened a door to social riches to their friends as well. For example, the March 8, 1907 Seattle Republican reported an evening of cards played at the Smiths’ rooms at the Concordia Club.

After the 1920s, the Concordia Club somehow dropped out of Seattle’s collective memory. In a 1974 oral history interview, real estate broker Henry Broderick mentioned that it was the hangout of Seattle pioneer Jacob Furth. Even at that time though, the interviewer replied, “I’ve never heard of it” (starting at minute 43). Concordia clubs were in cities across the United States and Canada, but it is not clear if they were directly connected.

Frank and Sadie lived at the club through at least 1910, when it was their home address in city directories and the 1910 census taken on April 22nd. Considering that they were there at the beginning, they were probably there at the end as well.

In February 1911 the old Hoge was demolished for construction of a new steel-framed, 18-story skyscraper: the new Hoge Building, tallest in Seattle. With demolition pending, the Concordia Club moved across Cherry Street to the Bailey Building. Per the April 11, 1911 Seattle Times, the smaller quarters meant it was missing the old dance floor and “a few other special accommodations”. That apparently meant no more accommodations for a steward.

Per Broderick, the club was “well appointed”. Frank and Sadie must have made many connections while living and working there.

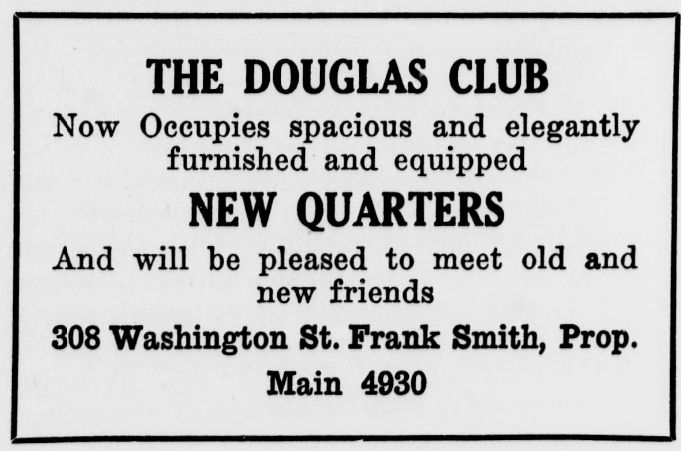

So in 1911 Frank leveraged those connections to open his own club. Instead of a private club for Jewish gentlemen, this would be a public social club that, like the Marquette, catered primarily to Black patrons.

Douglas Club, Frank’s Black social club

The Smiths lived at 416 19th Avenue East prior to living at Concordia, and moved back when Frank started his own business. He opened a Black social club, the Douglas Club, in 1911. The club started at 2nd and James in the Crown Building, soon moved to 307 3rd Ave South in the Mottman Building, and later moved to 308 South Washington St in the Tashiro/Kaplan Building.

The Douglas joined a group of Black social clubs in the decades-old red light district in Pioneer Square at the bottom of Washington Street. Later these clubs moved up Jackson Street and became famous as the cradle of Seattle’s jazz scene.

The club earliest discussed in local history was the Dumas. But descriptions of its start in 1917 at 10th and Jackson are not correct. Actually, it was already going in 1913 down at 2nd and Washington.

The Douglas Club, Dumas Club, and others in the area made occasional vice news. For example, in 1915 Felix Crane, who had managed both clubs at one time, was found guilty of relaying bribes to police. Otherwise their history is opaque, and it is difficult to determine who visited them and what transpired.

One reporter’s visit to Crane’s Cascade Saloon in early January 1915 does give us a glimpse, though. He described the well-dressed bartender serving up a series of drinks to mostly Black customers with some white people as well. A group of people played pool, and an older man warmed himself at a stove. There was a ragtime trio playing a tune:

“A nimble-fingered pianist… an athletic young [Black man] playing a bass drum, snare drum and a pair of cymbals all at once, and a big, coarse [Black man] singing in a thin, fine falsetto.”

Seattle Star, Jan 5, 1915

That’s the most insight available for the early 1910s clubs of Black owners like Frank Smith.

Prohibition gives police license for crime

After Washington State began Prohibition in 1916, alcohol busts became a problem for clubs in Seattle like Frank’s. In September that year Frank and his partner were arrested when a single pint of whiskey was found at the club.

Enforcement of liquor laws in Seattle was problematic, though. Many officers and leaders in the police department were deeply involved in shielding establishments and wealthy individuals from being caught for making and catering booze.

Frank Smith’s club needed to continue the bribery and police protection that Felix Crane had going even before Prohibition. Bribes flowed to the police in many directions: from the producers, the haulers, the sellers, and the restaurants, clubs, and back alley venues where people actually went to drink.

Starting in 1919, the most elaborate and free-flowing beer, liquor, and moonshine sales networks were run by the police themselves after national Prohibition. They took over the routes bringing alcohol from Canada and connected them to cities down the West Coast. The most infamous of the rumrunners was Roy Olmstead, but there were many more.

Frank Smith dies in chase

Although Frank Smith didn’t live long enough to see the transition to national Prohibition, he did experience the rise of police crime firsthand.

Frank’s Douglas Club somehow ran afoul of two dirty cops, Ed Hagen and Tom Clark. Hagen was recently profiled on this site. He had a history of helping organized crime, and his leadership eventually held him accountable for it. While no biography of Clark has been written yet, it is known that he later was part of Roy Olmstead’s crew, and then part of a Los Angeles-based rumrunning ring.

In the early hours of June 14, 1918, Hagen and Clark decided to bust Frank for purchasing whiskey. The story they told doesn’t make sense, at least at our current standards of evidence. Standing at 12th and Jackson, they saw him driving his car with shades pulled across the window. Supposedly that alone provoked them to get in their car and follow him.

Frank Smith drove his car a few blocks and met with another driver. Papers reported that they met at 14th Avenue South and King Street, but those streets have never intersected. He must have stopped his car at Rainier and King. The other driver handed Frank Smith a bag. That alone was enough for the policemen to begin the chase that ended Frank Smith’s life.

He fled east in his high horsepower car. Clark and Hagen found him again at 23rd and Yesler, and followed Frank Smith north on 23rd, east on Madison, and then south on Lake Washington Boulevard. At Leschi Park the police caught up to Smith and tried to yell at him to stop, a futile effort in the cacophony of 1910s automobiles.

Then they opened fire with their revolvers.

At the bottom of Atlantic Street in Mount Baker Park, Smith lost control of his car and rolled it. Perhaps as the papers reported, the turn was too sharp. Or, perhaps it was because of the volley of bullets hitting his car and tires.

What Frank Smith left behind

When Hagen and Clark approached the car, they found Frank Smith dead. According to his death certificate, Frank Smith died because of a “dislocation and fracture of the 3rd cervical vertebrae” — he broke his neck.

With him, Hagen and Clark found two passengers stuck under the car, still alive. These were Arthur Bradshire, a waiter at the Butler hotel, and musician Hence Brookins. Smith was giving them a ride home.

Both Bradshire and Brookins survived, but Bradshire require hospitalization. He did not cooperate when questioned by police, and the Seattle Times reported that he “became so violent at the [City Hospital] that it was necessary to place him in a straitjacket”.

The cause of the chase, the bag Smith took, did indeed have bottles of alcohol. The Seattle Times and Seattle P-I reporters agreed they were bottles of whiskey, but differed on their fate. One said the bag was under the car, bottles broken. The other said the bag was thrown nearby, with bottles intact. It’s strange that they were so important that a man died, but not important enough to describe correctly.

The Douglas Club was immediately locked up and condemned. It never appeared in news or directories again.

Sadie Smith and the house they lived in at 416 19th Ave E. carried on.

Community Aftermath

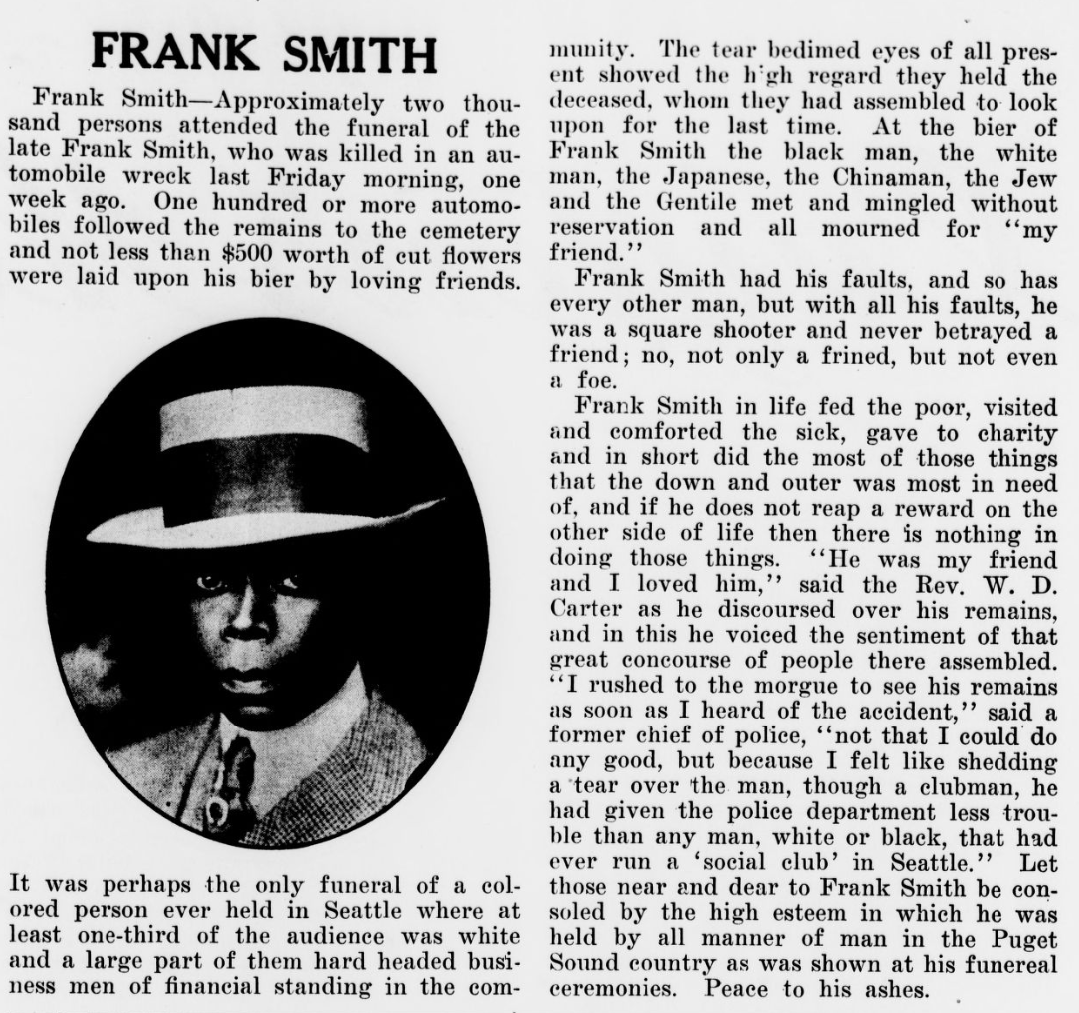

Frank Smith’s obituary ran in the June 22nd, 1918 Cayton’s Weekly, after his June 16th funeral. The Caytons remarked that more than 2,000 people attended. The procession from Collins Brothers mortuary (current site of Fleet Feet at 911 E. Pine St) to Lake View Cemetery had more than 100 cars.

The Caytons emphasized the mix of people at the funeral. Perhaps reflecting Frank Smith’s time as steward of the Concordia Club, his funeral had the most white people of any Black man or woman the Caytons could remember.

The entire obituary is worth reading, included here as an image.

Two weeks later the Caytons published a follow up. They commented on the high volume of sales of the edition with his obituary, and that his obituary was reprinted in papers in other cities. They reiterated, “He certainly had a host of friends.”

Seattle’s Black community was outraged at his death. The Seattle P-I described this two months later, after Ed Hagen killed another Black man:

“Feeling among a section of the colored population is said to have been especially severe against Hagen since the early morning chase some weeks ago when Frank Smith, proprietor of the Douglas Club, was killed in an automobile accident on Lake Washington Boulevard while Hagen and Sergeant Thomas Clark were in hot pursuit.”

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Aug 12, 1918

The Caytons later wrote in that Hagen and Clark were known to be involved in alcohol sales with Frank Smith. Two years later the community still wondered why Hagen and Clark turned on Smith:

“It’s a long lane that has no turning and both Ed [Hagen] and Tom Clark, of much Seattle police fame, must now feel that there is more truth than poetry in the statement. Some months ago both of these men were in good standing on the police force of this city and had things much their own way. They worked among the denizens of the underworld and charges and counter charges were frequently made by both sides.

“As the news came to me Frank Smith, proprietor of the Douglas Club, was the king of the bootleggers of the city and in this he was protected by [Hagen] and Clark, who shared in his ill-gotten gains. For some unexplainable reason one night when Frank was handling the stuff in his car [Hagen] and Clark set out to capture him and Frank, smelling mice, took flight.

“The chase became fast and furious, but Frank’s heavy touring car turned a sharp curve too rapidly and turned turtle, thus killing him instantly, and [Hagen] and Clark boasted of their capture. Men, who said they knew of the past relations between Smith and the two officers, wondered why they [pursued] him, on that fatal ride, and predicted that they would get theirs some day.

“[Hagen] is now under federal court conviction and Clark was caught one day this week, so goes the story, with the goods on him, and is now held by federal authorities. It’s a long lane that has no turn, and I am inclined to think that the ghost of Frank Smith stares into the cells of both [Hagen] and Clark and holds up a placard which reads, ‘I told you so.'”

Cayton’s Weekly, Mar 27, 1920

Sadie Smith’s life after Frank Smith

It’s fortunate that we know so much about Frank Smith. But, few words were written about Sadie Smith.

Sadie remarried Fred Sexias, a ship-board cook, in 1919. At least in 1920 Sadie worked as a waitress at a private home. They lived together in the house at 416 19th Avenue East.

Sexias became a labor leader in the Colored Marine Employment Benevolent Association. CMEBA was an anti-union organization, because labor unions were segregated, white-only groups. Sexias and Revels Cayton, son of the newspaper publishers, led CMEBA into an antiracial merger with the previously all-white union, the Maritime Cooks and Stewards Association of the Pacific.

Sadie and Fred Sexias moved to West Seattle in 1933, near where the West Seattle Golf Course soon opened.

Sadie Tipps died August 9, 1939 after a year-long struggle with lung cancer. Her funeral was at Bonney-Watson on Broadway, and her grave is alongside her father Blake, memorialized Blake Tipp, at Lake View Cemetery.

Further reading

Related articles by Rob Ketcherside:

- Rainier-Grand Hotel, where Frank worked after coming to Seattle

- Black families’ homes in 1909, for the context of the Smiths’ home-ownership

- Auto Row Apartments, Seattle’s first apartments built for Black tenants

- 1910 and 1920 non-white residents of Pike/Pine

- Foster Miller wedding (on Capitol Hill Seattle Blog), another story of contemporary racism

- Mt Zion’s time in Pike/Pine (on CHS Blog)

I’ve written related threads on Twitter. Here’s the first tweet in each thread:

- Thread on saloons with Black owners, aimed at Black patrons. That “wood” typo kills me.

- Thread on the Tashiro/Kaplan Building. Frank’s Douglas Club was here while it was known as the Exchange Building

- Thread on Hoge Building 1 demolition, which helped me understand why Frank changed jobs in 1910 or 1911.